Cultural Resources

|

|

CHRISTIAN EDUCATION/GRADUATION SUNDAY

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Sunday, May 20, 2012

Anthony B. Pinn, Lectionary Team Cultural Resource Commentator

I. Historical Considerations

Enslaved Africans and free Africans during the period of slavery were denied opportunity to learn to read and write. It was believed that those skills would encourage them to challenge the system of slavery and to rebel and that the economic benefits of free labor would be lost. Enslaved and free Africans, however, understood that education was a key to their freedom. By this they meant not only as a way to gain physical freedom through, for example, the ability to write passes that would allow them to travel beyond the plantation and escape the South; they also believed that education—the ability to read and write—would also give them greater access to the Word of God. They would be able to study Scripture themselves, and better understand the moral and ethical lessons found in the Bible.

They, and now their descendants, have recognized the need to study in order to maximize the benefits of scriptural teachings. Education provided an ability to discern the wisdom of Scripture for themselves—outside the teachings of those seeking to keep them oppressed. Study of the Bible, they believed, pleased God and fostered their growth as Christians living within the will of God.

|

As independent African American churches developed, one of their earliest missions was education. They developed classes and founded grade schools, high schools, and colleges, for the purpose of providing Christians opportunities to engage the Bible on their own and to prepare citizens and ministers who were able to teach the will of God through presentation of Bible stories and their meanings.

This desire for education as a way to promote study of Scripture as well as to promote secular education to advance African Americans has remained a major concern. The modern Civil Rights Movement, for instance, built on legal cases seeking to destroy restrictions on educational opportunities for African Americans. On the heels of the modern Civil Rights Movement, African Americans moved into colleges and universities in huge numbers in order to advance themselves and their community through study. Consistent with this push for secular education, churches fostered an appreciation for study and promoted opportunities for Christians to better understand and live out the principles of the faith—all achieved through education and study.

|

In addition to encouraging church members to seek educational opportunities for both spiritual and material reasons, African Americans historically have taken opportunity to celebrate education achievement. As churches have frequently provided economic support for those seeking education, they have also highlighted their successes during church services. Study of Scripture promotes spiritual growth that is manifest in the righteousness and ethical conduct of those involved, and churches have wanted to acknowledge the markers of secular education attainment as well. |

Despite the hard work of many African Americans and many churches over the years, it remains the case that large numbers of African Americans drop out of high school before their junior year, and more young men will encounter a prison cell than a college classroom in 2012. So, the successes—those young people who beat these odds—are acknowledged. Children who pass on to the next grade; young people who complete high school and move on to the next phase of educational life; those who complete college and graduate school and begin careers are all celebrated for their perseverance and hard work. Those whose devotion to biblical literacy motivates them to attend weekly Bible-study meetings and to conduct independent reading and study grow in spiritual insight, and moral-ethical commitments also are recognized. Because study of Scripture and higher education have been so vital to the life of African Americans, they are both embraced, encouraged, and honored within the context of churches. This was the case with the first study groups and colleges associated with African American churches, and it continues to this day.

II. Biographical Reflection

Dr. Anna Julia Cooper

|

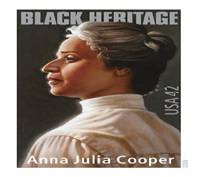

Religious communities have a longstanding interest in education for both secular and spiritual reasons. In fact, educational institutions and opportunities associated with churches often express a desire to link secular and spiritual knowledge to the general welfare and uplift of African Americans. And, over the course of the past two centuries, such church-based educational opportunities have enhanced African American life and thought. For example, Dr. Anna Julia Cooper’s educational advancement serves as a prime sign of the connections between spiritual advancement, socio-political insight, and educational opportunity. Cooper (1858–1964), deeply committed to the Church and the Christian faith, was the fourth African American woman to earn a PhD, when she graduated with a degree in history of the University of Paris-Sorbonne in 1924. However, her education began in 1868, when she enrolled in the school organized by the Episcopal Church in her state of North Carolina. While this school, like many others, assumed that women and men should undertake different courses of study, Cooper’s academic abilities and her tenacious push for greater opportunity resulted in her taking what had traditionally been the educational path reserved for men. Cooper graduated, but continued on as a teacher at the school before completing her own education with the highest academic degree possible. What Cooper is probably best known for is her book, A Voice from the South. Drawing on her education and religious commitment, Cooper used her studies as a way of thinking about the involvement of African American women in the political and religious life of the nation. For Cooper, life as a responsible and reasonable citizen and as a committed Christian required using her education to critique oppressive forces in society and in religious communities. Education, she would argue, must be used to promote self-determination and political change for African Americans as well as more productive and liberating interpretations of the Christian faith.

|

Cooper’s work and writings have served as inspiration for generations of students and religious leaders committed to using educational opportunity to advance the faith and transform the world. The strength of Cooper’s contributions to the life and advancement of democratic principles has been celebrated through a variety of honors, including a commemorative postal stamp. |

III. Songs That Speak to the Moment

Education—secular or religious—requires a willingness to learn, a desire to be taught. “Teach Me” by Hezekiah Walker expresses that desire to know, to learn, and to be taught and does so by lifting a character trait of significance to Christians who desire knowledge—patience.

Teach Me

Patience is a virtue I desire

(desire)

I need it when I have to go through the fire

(fire)

When You say no, it tells me what not to do

When You say yes, I know You’ll see me through

(see me through)

Waiting is a simple thing

That I must learn how to do

So teach me (teach me)

Teach me (teach me)

How to (how to wait)

Patience is a virtue I desire (desire)

I need it when I have to go through the fire

(fire)

When You say no, it tells me what not to do

(what not to do)

And when You say yes, I know You’ll see me through

(see me through)

Waiting is a simple thing

That we must learn how to do

So teach me (teach me)

Teach me (teach me)

How to (how to wait)

Patience is a virtue I desire (desire)

And I need it when I have to go through the fire

(fire)

Lord when You say no, it tells me what not to do

(what not to do)

And when You say yes, I know You’ll see me through

(see me through)

Waiting is a simple thing

That we must learn how to do

So teach me (teach me)

Teach me (teach me)

Say Lord (oh Lord teach me)

Teach me Jesus (teach me)

Say Lord (oh Lord teach me)

Teach me Jesus (teach me)

(repeat as directed)

Teach me how to wait

Wait

Teach me how to wait

Wait.1

For Christians, the purpose of study is to strengthen spiritual development and to enable closeness to God and God’s will. In a sense, it is to prevent there being anything that distracts from and stands between oneself and one’s faith. The gospel hymn “Nothing Between” by Charles A. Tindley speaks to this type of relationship to God’s will.

Nothing Between

Nothing between my soul and my Savior,

Naught of this world’s delusive dream:

I have renounced all sinful pleasure—

Jesus is mine! There’s nothing between.

Nothing between, like worldly pleasure;

Habits of life, though harmless they seem,

Must not my heart from Him ever sever—

He is my all! There’s nothing between.

Nothing between, like pride or station:

Self or friends shall not intervene;

Though it may cost me much tribulation,

I am resolved! There’s nothing between.

Nothing between, e’en many hard trials,

Though the whole world against me convene;

Watching with prayer and much self denial—

Triumph at last, with nothing between!

Nothing between my soul and the Savior,

So that His blessed face may be seen;

Nothing preventing the least of His favor:

Keep the way clear! Let nothing between.2

The discipline of the Christian faith requires work and a willingness to study and learn. As the following song indicates, one of the most important things that must be learned is prayer.

Hand in Hand

Now begin the heavenly race

The Savior calls today;

Let us early seek His face,

And early learn to pray.

Refrain

Hand in hand we’ll journey on,

Reaching forward to the prize,

Hoping, trusting in the Lord,

Where all our vigor lies.

He Who left His Father’s throne,

To suffer, bleed and die,

He Who made our grief his own,

Will every want supply.

Refrain

They who on His Name believe,

And patiently endure,

Life eternal shall receive,

And find His mercy sure.

Refrain

Now begin the heavenly race,

No more, no more delay;

To the healing fount of grace,

Rejoicing, haste away.

Refrain3

IV. Poetry and Quotes

Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave,

I am the dream and the hope of the slaves.

I rise

I rise

I rise.

| — Maya Angelou,“Still I Rise,”And Still I Rise (1978)4 |

The question is not whether we can afford to invest in every child; it is whether we can afford not to.

| — Marian Wright Edelman, The Measure of Our Success (1992)5 |

Nothing in all the world is more dangerous than sincere ignorance and conscientious stupidity.

| — Martin Luther King, Jr., Strength to Love (1963)6 |

Education helps one case cease being intimidated by strange situations.

| — Maya Angelou7 |

Some say we are responsible for those we love. Others know we are responsible for those who love us.

| — Nikki Giovanni8 |

You must invent your own games and teach us old ones how to play.

| — Nikki Giovanni9 |

V. Making This a Memorable Learning Moment

Many African Americans, and many African American churches, have made an effort to connect the growth and maturation of young people with the rituals and activities of Africa. For example, some have drawn from the practices of the Igbo of Nigeria to mark out and ritualize rites of passage for young men and young women. This process often involves the separating of the young people involved in the ritual from others for a set period of time, during which they are given special information about their new responsibilities as maturing members of the community—e.g., they learn about cooperation, the history of their people, the doctrines of their religious community.

VI. Learning More about This Moment

Videos

- “I Am a Promise: The Children of Stanton Elementary School.” New Video Group, 2005.

- “Mary McLeod Bethune: Champion for Education.” TMW Media Group, Inc., 2010.

- “60 Minutes—The Harlem Children’s Zone.” (CBS, 2006)

- “The Marva Collins Story.” Warner Home Video, 2008.

- “Waiting for Superman.” Paramount Vantage, 2010.

- “With All Deliberate Speed.” Starz/Anchor Bay, 2005.

Websites

- U.S. Department of Education. Online location: www.ed.gov/

- African American Child. Online location: www.aachild.com

- United Negro College Fund. Online location: www.uncf.org

- The Black Book Review. Online location: www.qbr.com/

Books

|

Anderson, James D. The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860–1935. Chapel Hill: The

University of North Carolina Press, 1988. |

|

Bell, Derrick. Silent Covenants: Brown V. Board of Education and the Unfulfilled

Hopes for Racial Reform. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. |

|

Perry, Theresa. Young, Gifted, and Black: Promoting High Achievement among

African-American Students. Boston: Beacon Press, 2004. |

|

Walker, Vanessa Siddle. Their Highest Potential: An African American School Community in the Segregated South. Chapel Hill: The University of North

Carolina Press, 1996. |

|

Watkins, William H. The White Architects of Black Education: Ideology and Power in America, 1865–1954. New York: Teachers College Press, 2001. |

|

Woodson, Carter G. The Mis-Education of the Negro. Seattle, WA: 2010. |

Notes

1. “Teach Me” by Hezekiah Walker. Pastor Hezekiah Walker Presents the LFT Church Choir. New York, NY: Zomba, 1998.

2. “Nothing Between” by Charles A. Tindley. African American Heritage Hymnal. Chicago, IL: GIA Publications, 2001. #397

3. “Hand in Hand.” Author unknown.

4. Maya Angelou, “Still I Rise.” Online location: http://www.infoplease.com/spot/bhmquotes1.html

5. Marian Wright Edelman. Online location: http://www.infoplease.com/spot/bhmquotes1.html

6. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Online location: http://www.infoplease.com/spot/bhmquotes1.html

7. Maya Angelou. Online location: http://famouspoetsandpoems.com/poets/maya_angelou/quotes

8. Nikki Giovanni. Online location: http://famouspoetsandpoems.com/poets/nikki_giovanni/quotes

9. Nikki Giovanni. Online location: http://famouspoetsandpoems.com/poets/nikki_giovanni/quotes