Cultural Resources

EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION DAY AND JUNETEENTH

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Sunday, January 1, 2012

The African American Lectionary Cultural Resources Team

| And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God. | |

| —Abraham Lincoln, The Emancipation Proclamation, January 1, 1863 |

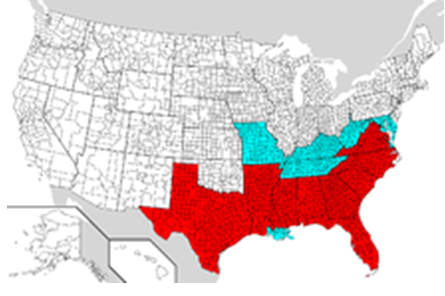

I. History

When it was enacted, the Emancipation Proclamation applied only in ten states that were still in rebellion in 1863. It did not cover the nearly 500,000 slaves in the slave-holding border states (Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, or Delaware) which were Union states—those slaves were freed by separate state and federal actions. The state of Tennessee had already mostly returned to Union control, so it was not named and was exempted. Virginia was named, but exemptions were specified for the 48 counties then in the process of forming the new state of West Virginia, seven additional Tidewater counties individually named, and two cities. Also specifically exempted were New Orleans and 13 named parishes of Louisiana, all of which were also already mostly under federal control at the time of the Proclamation. These exemptions left unemancipated an additional 300,000 slaves.1

|

(Areas covered by the Emancipation Proclamation are in red. Slave-holding areas not covered are in blue.) |

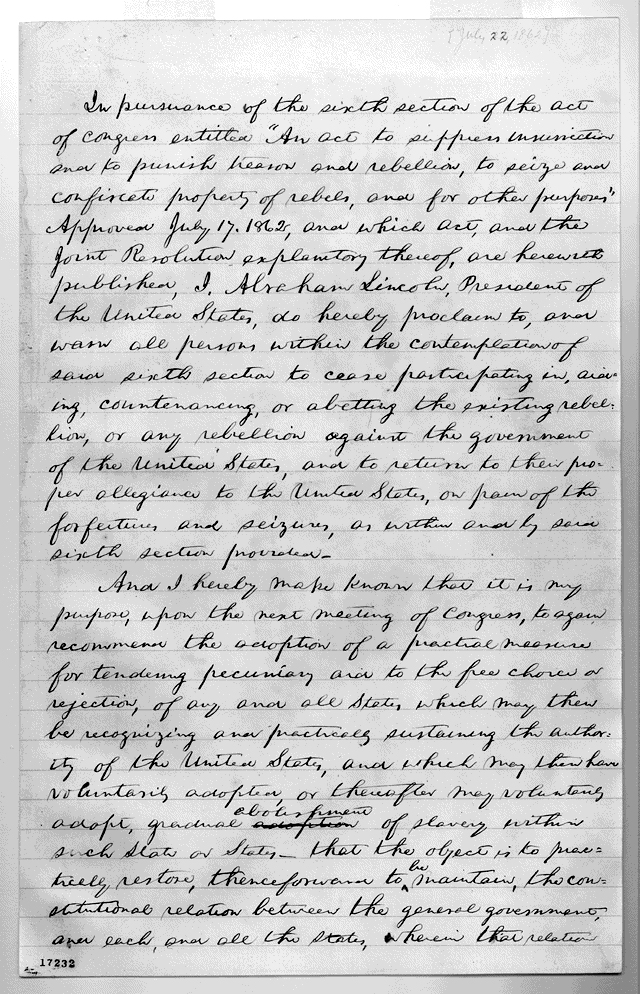

The Proclamation was issued in two parts. The first part, issued on September 22, 1862, was a preliminary announcement outlining the intent of the second part, which officially went into effect 100 days later on January 1, 1863, during the second year of the Civil War. It was Abraham Lincoln’s declaration that all slaves would be permanently freed in all areas of the Confederacy that had not already returned to federal control by January 1863. The ten affected states were individually named in the second part (South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina). Not included were the Union slave states Maryland Missouri, and Kentucky. Also not named was the state of Tennessee, which was at the time more or less evenly split between the Union and Confederacy. Specific exemptions were stated for areas also under Union control on January 1, 1863, namely 48 counties that would soon become West Virginia, seven other named counties of Virginia and New Orleans and 13 named parishes nearby.2

Winning re-election, Lincoln pressed the lame duck 38th Congress to pass the proposed amendment immediately rather than wait for the incoming 39th Congress to convene. In January 1865, Congress sent to the state legislatures for ratification what became the Thirteenth Amendment, banning slavery in all U.S. states and territories. The amendment was ratified by the legislatures of enough states by December 6, 1865, and proclaimed 12 days later. There were about 40,000 slaves in Kentucky and 1,000 in Delaware who were liberated then.3

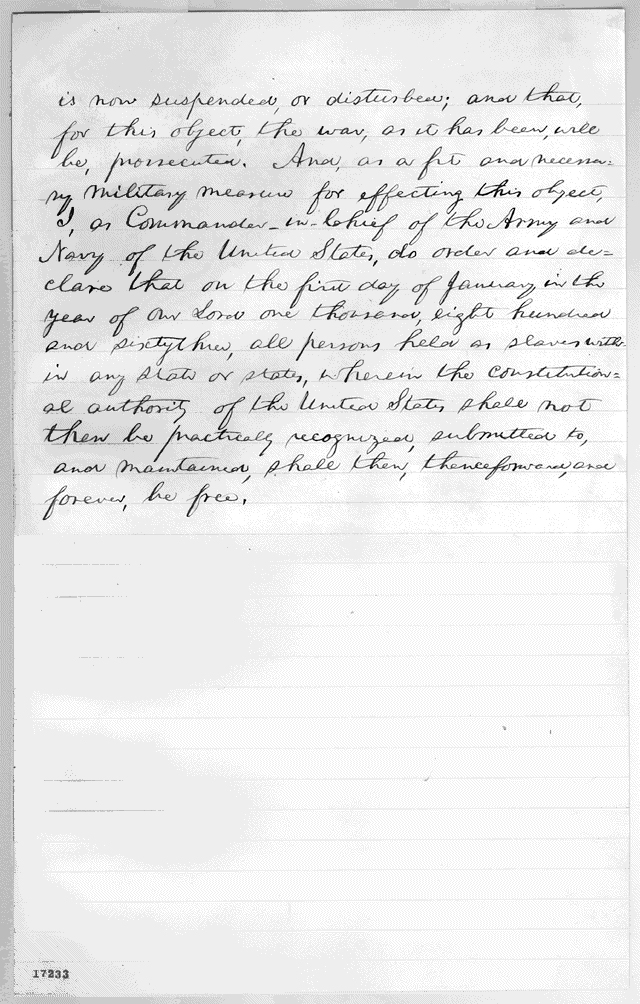

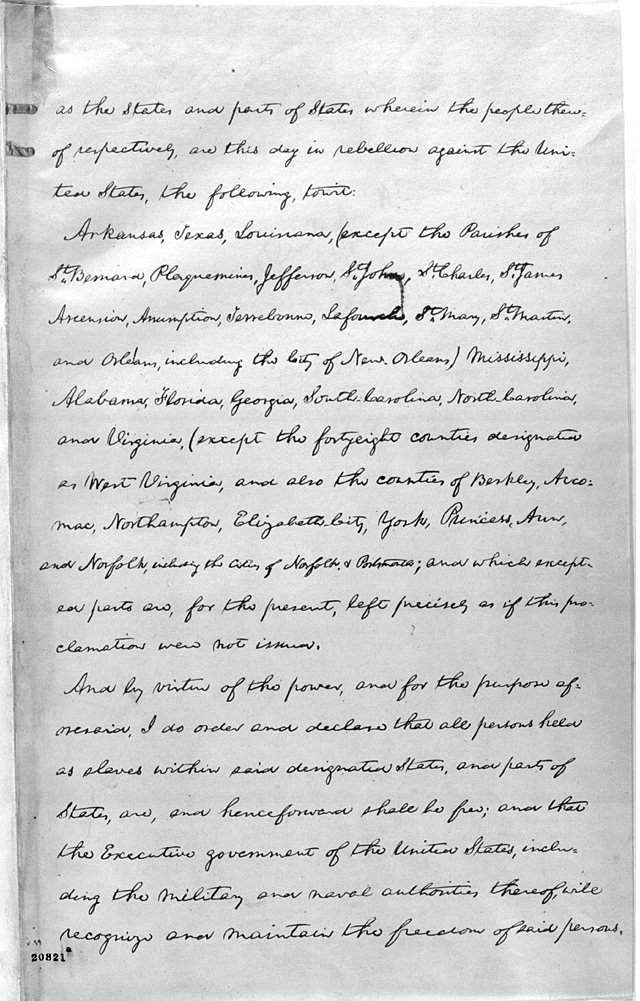

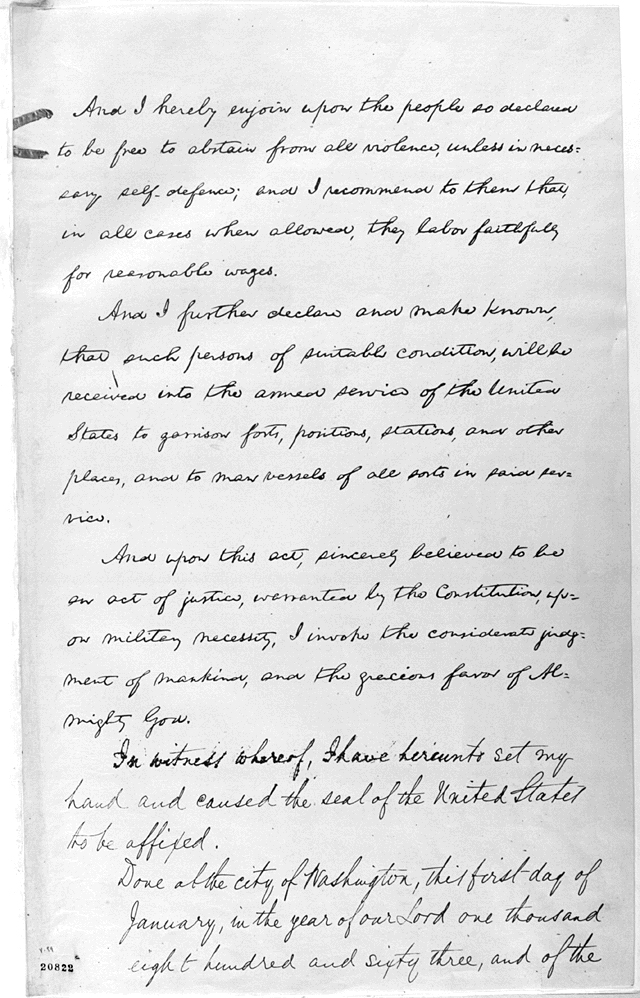

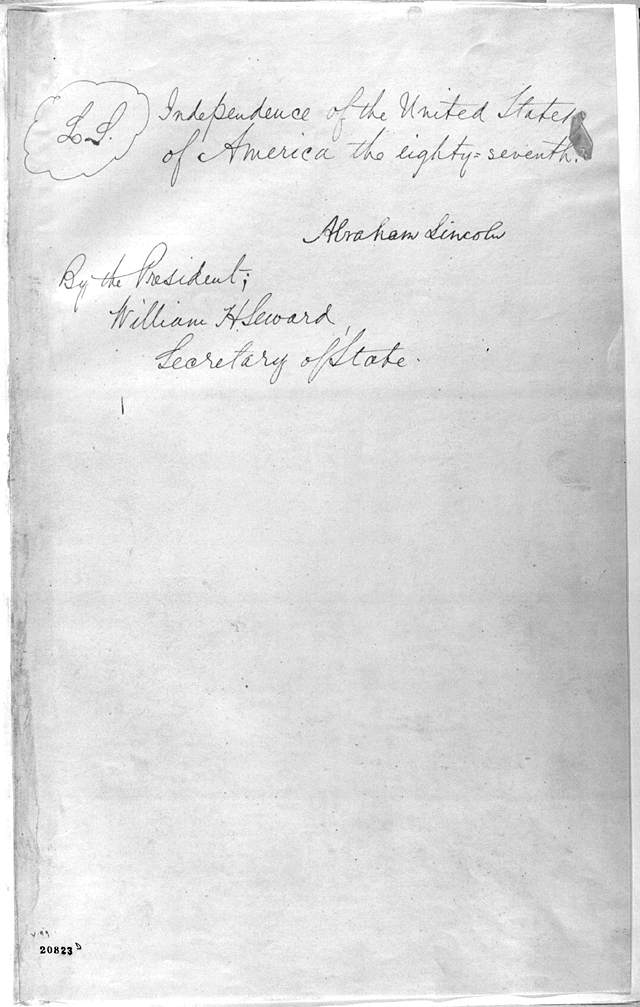

A draft of the proclamation was written by President Lincoln before the final proclamation was issued. The handwritten draft is provided below taken from the Robert Todd Lincoln Family Papers, Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress.

|

|

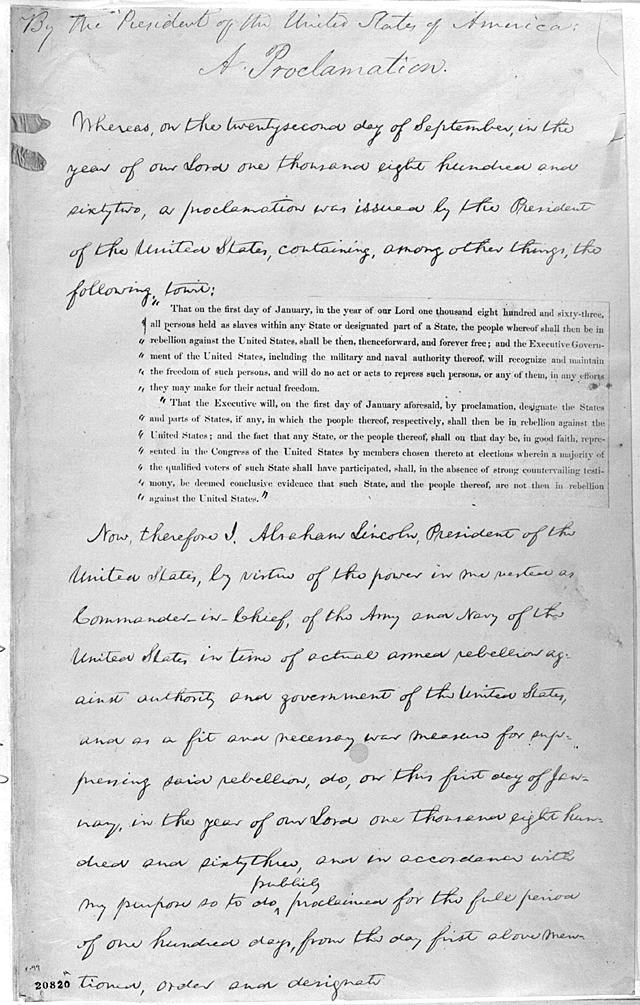

Below is the final written copy of the Proclamation taken from the Robert Todd Lincoln Family Papers, Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress.

|

|

|

|

II. Comments Concerning Slavery and Emancipation

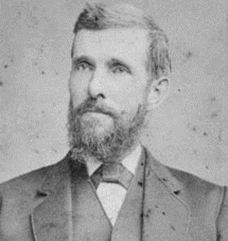

Rev. William Weston Patton (1821–1889) was president of Howard University, an abolitionist, and one of the contributors to the words of John Brown’s Body. He was the son of a minister. Patton was chairman of the committee that presented to President Lincoln, in 1862, the memorial from Chicago asking him to issue a proclamation of emancipation. In 1886, on behalf of the freedmen (a group that worked to end slavery, provide education for blacks, and provide funding for Black abolitionists), Patton went to Europe to gain their support for the ending of slavery and to raise funds for abolitionist causes.

John Brown’s Body

In October 1861 Patton wrote new lyrics to the battle song John Brown’s Body. These were published in the Chicago Tribune on December 16, 1861. The new lyrics glorify the violent acts of the abolitionist John Brown and his followers. The third verse directly refers to the attack on the armory in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia . Verse four compares John Brown to John the Baptist.

He captured Harper’s Ferry, with his nineteen men so few,

And frightened “Old Virginny” till she trembled thru and thru;

They hung him for a traitor, themselves the traitor crew,

But his soul is marching on.

John Brown was John the Baptist of the Christ we are to see,

Christ who of the bondmen shall the Liberator be,

And soon thruout the Sunny South the slaves shall all be free,

For his soul is marching on.

Nell Irvin Painter, Edwards Professor of American History at Princeton, pioneered a new field in the study of slavery. In her work Soul Murder and Slavery, Painter examines the psychological impact that the institution has on both black and white people. She looks at the effects of slavery-produced trauma on children especially, and at the culture that is created in a world based on domination and ownership. Her work is also excerpted in a book entitled Black on White: Black Writers on What It Means to Be White, edited by David R. Roediger. Painter said in Black on White:

Let’s take, for instance, a large plantation household. There we would find the owning family and probably more than just one or two generations, and probably more than just the nuclear family. But we’d also find working people, enslaved working people who then would be called servants. Some of them would actually sleep in the bedrooms of their owners, and they would be in very close contact.

So we have families that are made up of people who are not necessarily biologically connected, but because they’re together so much, they get psychologically connected. And you can be connected to someone whom you hate, but that person is very important in your life. And that’s the kind of relationship that thinking “black-white color line” completely obscures. So we need to be able to see how, across the color line as well as within the color line, we have psychological dynamics and sometimes physical dynamics as well.

And when we talk about this terrible thing of violence in slave society, we need to think of many people, many kinds of people as victims and as perpetrators, for that matter, because violence can be inter-generational, and violence can spread to people who in one situation are victims but in another situation may be perpetrators.

So for instance, let’s take the very common scene of whips and beating of someone because they have not done their work properly, according to their overseer or their owner. So the master beats the worker. “You didn’t do your work right.” Tch-tch-tch-tch. But seeing this are perhaps that slave’s children and that master’s children.

And psychologists talk about triangles. So you have the person being beaten, the person doing the beating, and the observer. And the observer needs to identify with one or the other. Slave children would tend to identify with their mother, their father, their uncle, and think of themselves as victims. And they would be victimized in their turn. Slaving children can go either way. And southern society, at least, was set up in such a way that girls could identify with the victim and could identify with victims as women. We have a whole stereotype of the mistress who is the nurse on the plantation, who takes care of people. But the boy must learn to identify with the beater. If he doesn’t, then he’s not fully a man. So that makes the ability to inflict violence an integral part of one’s manhood.

John Nelson was a Virginian who spoke in 1839 about his own coming of age and this system of triangles. He says, when he was a child, when his father beat their slaves, that he would cry and he would feel for the slave who was being inflicted with violence. He would feel almost as if he himself were being beaten, and he would cry. And he would say, “Stop, stop!” And his father said, “You have to stop that. You have to learn to do this, yourself.” And as John Nelson grew up, he did learn how to do it. And he said in 1839 that he got to the point where he not only didn’t cry; he could inflict a beating himself and not even feel it.

Someone who can do that is going to cut off a whole world of feeling, and make the larger system of obedience and submission into one of the great values, one of the great moral values. Obedience and submission are hallmarks of slavery. They’re also hallmarks of patriarchy, because the patriarch has people below him who owe him obedience and submission: people in his own family, his slaves, his poor relations, his wife. And then there’s also Christianity, in which pious people owe obedience and submission to God. So if you put together slavery, patriarchy, and evangelical Christianity, you’ve got a lot of violence and submission.

One thing I found very interesting when I started working on soul murder and slavery is that we have a new literature of trauma that’s come out of the Vietnam War. But none of that sees slaves as people who endured trauma. In American history, those people are the perfect victims of trauma, and we can now learn a great deal about what they were likely to feel, or want to do, or try to get away from, or their symptoms, for instance, because we know about what trauma can do to people.

Within this plantation household, little kids would be learning lessons. Little kids learn lessons all the time. That’s how they grow up. And so a white child would learn lessons, as well as black children. A white child seeing the violence that goes on between owners and slaves learns: “Well, I can do that. I have power too.” And I’ve read many an anecdote from slaves and from slaveowning families about the point where the white child no longer plays with the black children as an equal, but begins to give them orders—around 5, 6, 7. And so the child, the white child learns that he can give orders and that she can give orders, but not quite in the same way. But the great lesson is that I (child) can inflict violence, can give orders, must be obeyed, and I am someone to whom others owe submission.

One of the figures who appears over and over again in fiction and non-fiction about the slaveholding South is the jealous mistress. And in fact, Harriet Jacobs (Linda Brent) has a chapter in Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl entitled “The Jealous Mistress.” So we have a triangle between the master and the enslaved woman whom he forces or to whom he is linked sexually. And then we have the mistress, the jealous mistress. And we realize the dynamic between the jealous mistress and the master. She’s jealous. But there’s also another dynamic going on (another kind of attachment, if you wish), that the slave woman, who’s usually quite young, may feel that the mistress has abandoned her, in the way that young women who are incest victims tend to blame their mother more than their father or stepfather or uncle. So you have a dynamic between the two women that we don’t usually focus on.

Some years ago, I had the pleasure of working on a large journal that a plantation mistress in Georgia [Ella Gertrude Clanton Thomas] had generated between 1848 and 1889. So it’s a big document. And in that document I found: She was aware that her husband was involved with a woman of color, probably over the generations, and that the husband and the slave woman had had a child, about the same age as her son. The mistress never wants to admit that she knows about this relationship and that it troubles her. But the issue of competition between women appears over and over and over in the journal.

And at one point, after the Civil War, she’s looking out on a field and she’s seeing her son (whom she feels, of course, should be in college) plowing. And he’s plowing with the slave woman’s child. And the slave woman’s boy, he’s not in college either. But the mistress feels that there’s a competition between these two boys, and the fact that they are both in the field plowing shows how her son has fallen and this other woman’s son is poised to rise. So she has a complicated psychological dynamic that comes out of this kind of complicated family.

This same woman tried to erase a story out of her journal. It’s a moment when she really is most tortured. And in this moment, she realizes that not only she is involved in adulterous triangle, but also her mother had been. That is, her father had a slave woman, and had had children by another woman. So in 1864, Ella Gertrude Clanton Thomas (known as Gertrude Thomas) is reading the will that her father has left. He’d just died in 1864. And she realizes that she stands to inherit her half-brothers and sisters. This woman is a devout Methodist, realizes all the terrible Biblical problems here, and the moral issues. And she’s completely destroyed by the idea that she could own her brothers and sisters. But this kind of monstrous situation was one that came out of the dynamics of slavery time and time again.4

This following article by James Baldwin appeared in December 1962 as part of a special issue of the Progressive Newspaper marking the one-hundredth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. It is a letter to his nephew, James.

Dear James:

Other people cannot see what I see whenever I look into your father’s face, for behind your father’s face as it is today are all those other faces which were his. Let him laugh and I see a cellar your father does not remember and a house he does not remember and I hear in his present laughter his laughter as a child. Let him curse and I remember his falling down the cellar steps and howling and I remember with pain his tears which my hand or your grandmother’s hand so easily wiped away, but no one’s hand can wipe away those tears he sheds invisibly today which one hears in his laughter and in his speech and in his songs.

I know what the world has done to my brother and how narrowly he has survived it and I know, which is much worse, and this is the crime of which I accuse my country and my countrymen and for which neither I nor time nor history will ever forgive them, that they have destroyed and are destroying hundreds of thousands of lives and do not know it and do not want to know it. One can be—indeed, one must strive to become—tough and philosophical concerning destruction and death, for this is what most of mankind has been best at since we have heard of war; remember, I said most of mankind, but it is not permissible that the authors of devastation should also be innocent. It is the innocence which constitutes the crime.

Now, my dear namesake, these innocent and well-meaning people, your countrymen, have caused you to be born under conditions not far removed from those described for us by Charles Dickens in the London of more than a hundred years ago. I hear the chorus of the innocents screaming, “No, this is not true. How bitter you are,” but I am writing this letter to you to try to tell you something about how to handle them, for most of them do not yet really know that you exist. I know the conditions under which you were born for I was there. Your countrymen were not there and haven’t made it yet. Your grandmother was also there and no one has ever accused her of being bitter. I suggest that the innocent check with her. She isn’t hard to find. Your countrymen don’t know that she exists either, though she has been working for them all their lives.

Well, you were born; here you came, something like fifteen years ago, and though your father and mother and grandmother, looking about the streets through which they were carrying you, staring at the walls into which they brought you, had every reason to be heavy-hearted, yet they were not, for here you were, big James, named for me. You were a big baby. I was not. Here you were to be loved. To be loved, baby, hard at once and forever to strengthen you against the loveless world. Remember that. I know how black it looks today for you. It looked black that day too. Yes, we were trembling. We have not stopped trembling yet, but if we had not loved each other, none of us would have survived, and now you must survive because we love you and for the sake of your children and your children’s children.

This innocent country set you down in a ghetto in which, in fact, it intended that you should perish. Let me spell out precisely what I mean by that for the heart of the matter is here and the crux of my dispute with my country. You were born where you were born and faced the future that you faced because you were black and for no other reason. The limits to your ambition were thus expected to be settled. You were born into a society which spelled out with brutal clarity and in as many ways as possible that you were a worthless human being. You were not expected to aspire to excellence. You were expected to make peace with mediocrity. Wherever you have turned, James, in your short time on this earth, you have been told where you could go and what you could do and how you could do it, where you could live and whom you could marry.

I know your countrymen do not agree with me here and I hear them saying, “You exaggerate.” They do not know Harlem and I do. So do you. Take no one’s word for anything, including mine, but trust your experience. Know whence you came. If you know whence you came, there is really no limit to where you can go. The details and symbols of your life have been deliberately constructed to make you believe what white people say about you. Please try to remember that what they believe, as well as what they do and cause you to endure, does not testify to your inferiority, but to their inhumanity and fear.

Please try to be clear, dear James, through the storm which rages about your youthful head today, about the reality which lies behind the words “acceptance” and “integration.” There is no reason for you to try to become like white men and there is no basis whatever for their impertinent assumption that they must accept you. The really terrible thing, old buddy, is that you must accept them, and I mean that very seriously. You must accept them and accept them with love, for these innocent people have no other hope. They are in effect still trapped in a history which they do not understand and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it. They have had to believe for many years, and for innumerable reasons, that black men are inferior to white men.

Many of them indeed know better, but as you will discover, people find it very difficult to act on what they know. To act is to be committed and to be committed is to be in danger. In this case the danger in the minds and hearts of most white Americans is the loss of their identity. Try to imagine how you would feel if you woke up one morning to find the sun shivering and all the stars aflame. You would be frightened because it is out of the order of nature. Any upheaval in the universe is terrifying because it so profoundly attacks one’s sense of one’s own reality. Well, the black man has functioned in the white man’s world as a fixed star, as an immovable pillar, and as he moves out of his place, heaven and earth are shaken to their foundations.

You don’t be afraid. I said it was intended that you should perish, in the ghetto, perish by never being allowed to go beyond and behind the white man’s definition, by never being allowed to spell your proper name. You have, and many of us have, defeated this intention and by a terrible law, a terrible paradox, those innocents who believed that your imprisonment made them safe are losing their grasp of reality. But these men are your brothers, your lost younger brothers, and if the word “integration” means anything, this is what it means, that we with love shall force our brothers to see themselves as they are, to cease fleeing from reality and begin to change it, for this is your home, my friend. Do not be driven from it. Great men have done great things here and will again and we can make America what America must become.

It will be hard, James, but you come from sturdy peasant stock, men who picked cotton, dammed rivers, built railroads, and in the teeth of the most terrifying odds, achieved an unassailable and monumental dignity. You come from a long line of great poets, some of the greatest poets since Homer. One of them said, “The very time I thought I was lost, my dungeon shook and my chains fell off.”

You know and I know that the country is celebrating one hundred years of freedom one hundred years too early. We cannot be free until they are free. God bless you, James, and Godspeed.

Your uncle,

JAMES5

III. Songs That Speak to the Moment

Free at Last

Free at last, free at last

Thank God almighty, I’m free at last

Free at last, free at last

Thank God almighty, I’m free at last

Satan’s mad and I am glad

Thank God almighty, I’m free at last

He missed this soul he thought he had.

Thank God almighty I’m free at last.

You can hinder me here but you cannot there

There’s a God in heaven and he answers prayer.

Only chain that I can stand

Is the chain that links hand to hand

Thank God almighty I’m free at last.6

Charles Albert Tindley (1851–1933) wrote many timeless songs. Although he wrote them for a particular audience and addressed very specific periods in history, they still apply to much of the current human condition. In the song “A Better Day Is Coming” Tindley’s lyrics were written with blacks in slavery in mind and their condition years after Emancipation. However, clearly the words of the song are still the plea of so many today. In the song “Here I May Be Weak and Poor (God Will Provide for Me),” one can almost close his or her eyes and see those who suffered the savagery of slavery, the un-kept promises of Emancipation, and even those who now suffer devastation due to the greed of others. In “The World of Forms and Changes (After awhile)” he again addresses timeless subjects such as fear over tainted products. He says: “The world of forms and changes [i]s just now so confused. That there is found some danger [i]n everything you use.” As the next food recall occurs, Tindley was again on the mark. Then, he speaks of the greed that was permeating the country in his day. He says, “Our boated land and nation, [a]re plunging in disgrace; with pictures of starvation, almost in every place; while loads of needed money, remain in hoarded piles; but God will rule this country, after awhile.” As people occupy Wall Street and other streets around the world in the fall of 2011, this verse of “The World of Forms and Changes” is so relevant.

A Better Day Is Coming

1. A better day is coming,

the morning draweth nigh,

When girded right with holy might

shall overthrow the wrong,

When Christ our Lord shall listen

to every plaintive sigh,

and stretch his hand o’er every land

in justice by and by.

Chorus

‘Tis coming by and by,

‘Tis coming by and by

A better day is coming,

the morning draweth nigh.

‘Tis coming by and by,

‘Tis coming by and by,

The welcome dawn is hastening on,

‘Tis coming by and by.

2. The boars of haughty error

no more shall fill the land,

While men enraged their powers engaged,

to kill their fellow man,

But God the Lord shall triumph,

and Satan’s host shall fly,

For wrong must cease and righteousness

shall conquer by and by.

Chorus

‘Tis coming by and by,

‘Tis coming by and by

A better day is coming,

the morning draweth nigh.

‘Tis coming by and by,

‘Tis coming by and by,

The welcome dawn is hastening on,

‘Tis coming by and by.

3. No more will angry nations

In deadly conflict meet,

While children cry and parents die

in conquest or defeat,

For Jesus Christ the Captain,

will give the battle cry,

The Holy Ghost will lead the host

to victory by and by.

Chorus

‘Tis coming by and by,

‘Tis coming by and by

A better day is coming,

the morning draweth nigh.

‘Tis coming by and by,

‘Tis coming by and by,

The welcome dawn is hastening on,

‘Tis coming by and by.

4. No more shall lords and rulers

Their helpless victims press

and bar the door against the poor

and leave them in distress,

But God, the King of Glory,

who hears the ravens cry,

will give command that every man

have plenty by and by.

Chorus

‘Tis coming by and by,

‘Tis coming by and by

A better day is coming,

the morning draweth nigh.

‘Tis coming by and by,

‘Tis coming by and by,

The welcome dawn is hastening on,

‘Tis coming by and by.7

Here I May Be Weak and Poor (God Will Provide for Me)

1. Here I may be weak and poor,

With afflictions to endure;

All about me not a ray of light to see.

Just as He has often done,

For his helpless trusting ones,

God has promised to provide for me.

Chorus

God has promised to provide for me,

God has promised to provide for me;

All creation is His own,

All my needs to him are known.

He has promised to provide for me.

2. All my raiment and my food,

And my health and all that’s good,

Are within His own written guarantee,

God is caring for the poor,

Just as He has done before,

He has promised to provide for me.

Chorus

God has promised to provide for me,

God has promised to provide for me;

All creation is His own,

All my needs to him are known.

He has promised to provide for me.

3. Mighty men may have control,

Of the silver and the gold;

Want and sorrow for the poor there may be,

But the God of heaven reigns,

And his promise is the same,

And I know He will provide for me.

Chorus

God has promised to provide for me,

God has promised to provide for me;

All creation is His own,

All my needs to him are known.

He has promised to provide for me.

4. Ancient Israel heard His voice,

How the people did rejoice,

When he lead them safely thro’ the mighty sea.

In the wilderness they knew,

What the living God can do;

He’s the one that doth provide for me.

Chorus

God has promised to provide for me,

God has promised to provide for me;

All creation is His own,

All my needs to him are known.

He has promised to provide for me.

5. When they hadn’t any bread,

Good old Moses knelt and prayed;

And the God who gives plentiful and free,

Sent the precious manna down,

Israel saw it on the ground;

‘Twas the God who now provides for me.

Chorus.8

The World of Forms and Changes (After awhile)

The world of forms and changes

Is just now so confused

That there is found some danger

In everything you use;

But this is consolation

To every blood washed child:

The Lord will change our nation

After awhile.

2. Old Satan tries to throw down

Everything that’s good;

He’d fix a way to confound

The righteous if he could.

But thanks to God Almighty

That he cannot beguile;

And he will be done fighting

After awhile.

Chorus

After awhile,

After awhile

The Lord will change our situation

After awhile.

6. Our boasted land and nation,

Are plunging in disgrace;

With pictures of starvation

Almost in every place;

While loads of needed money,

Remain in hoarded piles;

But God will rule this country,

After awhile.

Chorus

After awhile,

After awhile

The Lord will change our situation

After awhile.9

IV. A Few Words about Juneteenth

Sharon Fuller provided the following information in the 2009 worship unit for Emancipation Proclamation/Juneteenth:

What is Juneteenth?

June 19th is perhaps the oldest holiday celebrated by African Americans; it is the grandfather of all such observances. Juneteenth is a cultural observance. June 19, 1865 marks the date all slaves in the United States were officially made free.” (See the material above for the specific regarding who was free.)

Who developed Juneteenth?

Freed slaves in the state of Texas created and developed the June 19th celebration in 1866. Legend has it that the name Juneteenth was derived from a little Negro girl who could not pronounce June 19. She said Juneteenth and the name caught on and was used throughout the state of Texas

When is Juneteenth observed?

Juneteenth is officially observed on June 19; however, the celebration may last one to seven days. On this lectionary it is slated for celebration for January 1 and has been joined with Emancipation Proclamation Day for two reasons. First, the Emancipation Proclamation was given effect on January 1, 1863. Second, during the earliest Juneteenth celebrations the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation took center stage. Our goal is to give historical coverage to both events, understanding that Juneteenth is now almost always celebrated in June.

Where is Juneteenth observed?

This American holiday is celebrated primarily by African Americans and was originally celebrated by freed slaves located in the state of Texas. Juneteenth is now celebrated by many throughout the world.

Why is Juneteenth observed?

Juneteenth is observed to acknowledge that all slaves within the continental United States were freed at a certain point. This celebration acknowledges the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation while also acknowledging that the slaves of the states of Texas did not receive the news until almost 2˝ years after the official signing of the announcement was given. Large celebrations began in 1866.

African American in Texas treat this day like the Fourth of July, and the celebrations contain similar events. In the 1800s, the celebrations included a deeply religious tone: prayer services, speakers with inspirational messages, and preaching, after which the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation was followed by stories from former slaves. Barbeque, red soda water, desserts, and watermelon were served and enjoyed by all. Various games were played while rodeos and dances became serious contests for participants and the crowds alike.

V. Websites and Books for Emancipation Proclamation Day and Juneteenth

- See the National Endowment for the Humanitie’s Edsitement website for information to teach children and youth about the Emancipation Proclamation. Online location: http://edsitement.neh.gov/lesson-plan/emancipation-proclamation-freedoms-first-steps

- See the National Archives (American Originals) section for information to teach children and youth about the Emancipation Proclamation. Online location: http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/american_originals_iv/sections/emancipation_proclamation.html

- Visit the Library of Congress website for information on the Emancipation Proclamation. Online location: http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/EmanProc.html

- See the Library of Congress for the complete Abraham Lincoln Papers. They consists of approximately 20,000 documents. In its online presentation, the Abraham Lincoln Papers comprise approximately 61,000 images and 10,000 transcripts.

- Guelzo, Allen C. “How Abe Lincoln Lost the Black Vote: Lincoln and Emancipation in the African American Mind,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association (2004) online edition.

- Holzer, Harold, Edna Greene Medford, and Frank J. Williams. The Emancipation Proclamation: Three Views. Louisiana State University Press, 2006.

- Kachun, Mitch. Festivals of Freedom: Memory and Meaning in African American Emancipation Celebrations, 1808–1915. University of Massachusetts Press, 2006.

- McPherson, James M. and James K. Hogue. Ordeal by Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction. McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/Languages; 4th edition, 2010. esp. pp. 316–321.

Notes

1. Foner, Eric. The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery. New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 2010. pp. 241–242.

2. The Emancipation Proclamation.” Online location: www.wikipedia.org/EmacipationProclamation accessed 1 October 2011

3. Online location: http://www.sonofthesouth.net/

4. Painter, Nell Irvin. “Slavery and Soul Murder.” Black on White: Black Writers on What It Means to Be White, ed. David R. Roediger. New York, NY: Schocken, 1999.

5. Baldwin, James, “A Letter to My Nephew.” Progressive Newspaper, December 1962. Online location: http://www.progressive.org/archive/1962/december/letter

6. “Free at Last.” Negro Spiritual

7. Tindley, Charles Albert. “A Better Day Is Coming.” Beams of Heaven: Hymns of Charles Albert Tindley (1851–1933) Singer’s Edition. #40. S.T. Kimbrough, Jr. ed., Carlton R. Young, Music ed. General Board of Global Ministries, The United Methodist Church, New York, NY, 2006.

8. Tindley, Charles Albert. “Here I May Be Weak and Poor (God Will Provide for Me).” Beams of Heaven. #34

9. Tindley, Charles Albert. “The World of Forms and Changes (After awhile).” Beams of Heaven. #35