Cultural Resources

KWANZAA

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Saturday, December 26, 2009 – January 1, 2010

Maulana Karenga, Guest Cultural Resource Commentator

Creator of Kwanzaa and the Nguzo Saba, Professor of Africana Studies, California State University, Long Beach, CA

I. Historical Background

Kwanzaa

A Celebration of Family, Community, and Culture

Kwanzaa is an African American and Pan-African holiday which celebrates family, community and culture with emphasis on creating, harvesting and sharing good in the world. Its name comes from the Swahili words matunda ya kwanza which mean “first fruits” and reflects the holiday’s roots in African harvest celebrations which bear various names according to the language of the society which celebrates them. Some of these are: Pert-en-Min in ancient Egypt, Umkhosi in Zululand, Incwala in Swaziland, Odwira in Ashantiland, and Odu Ijesu in Yorubaland.

I created Kwanzaa in 1966 in the United States. Kwanzaa begins on December 26 and continues through January 1. Kwanzaa is rooted in ancient African history and culture, but it was developed in the modern context of African American life and struggle as a reconstructed and expanded African tradition. Moreover, Kwanzaa is developed out of Kawaida philosophy which stresses cultural grounding, value-orientation and an ongoing dialog with African culture, continental and diasporan, in pursuit of paradigms of human excellence and human possibility.

As explained in my book Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture (2008), the celebration of Kwanzaa is first rooted in the ancient and ongoing African ethical tradition and commitment to bring, increase and sustain good in the world. It is at the same time reaffirmation of the ancient ancestral teachings that the greatest good is shared good; that we must conceive it and cultivate it together, harvest it together and share it throughout the world. For surely the Divine gift of the good of the world and in the world belongs to everyone. It is within this concept of cooperatively created and shared good that we grasp the expansive meaning of the ancient harvests and harvest celebrations in which the ancient origins of Kwanzaa are based and modeled, for they offer us models of the cooperative creation, sharing and celebration of good in and for the world.

Second, Kwanzaa’s modern roots are in the reaffirmation of the 60s, that historical period of sustained struggle to free ourselves and to reaffirm our Africanness and our social justice tradition. And this too was/is an affirmation and reaffirmation of our ancient and ongoing commitment to bring, increase and sustain good in the world. For it was an earnest and exacting struggle for freedom in its fullest sense, for justice in its most expansive meaning, power of a people over their destiny and daily lives and for a just and enduring peace in the world. And, of course, the reaffirmation of the 60s was a struggle to return to our own history and culture, to speak our own special cultural truth and make our own unique contribution to the ethical reconstruction of the country and to the expansion of good in the world.

II. The Nguzo Saba and Other Kwanzaa Symbols

At the heart of the meaning and activities of this seven-day holiday are the Nguzo Saba (The Seven Principles), developed by the author, which are aimed at reaffirming and strengthening family, community and culture. These principles are: Umoja (Unity), Kujichagulia (Self-Determination), Ujima (Collective Work and Responsibility), Ujamaa (Cooperative Economics), Nia (Purpose), Kuumba (Creativity), and Imani (Faith). Each day of Kwanzaa is dedicated to one of the principles and is organized around activities and discussion to emphasize each principle. Also, at the evening meal, family members light one of the seven candles each night to focus on the principles in a ritual called “lifting up the light that lasts;” that is to say, upholding the Nguzo Saba and all the other life-affirming and enduring principles which reaffirm the good of life, enrich human relations and support human flourishing.

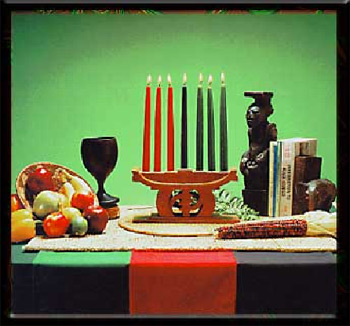

In addition to the mishumaa saba (seven candles),the other basic symbols of Kwanzaa are: the mazao (crops), symbolic of African harvest celebrations and of the rewards of productive and collective labor; mkeka (mat), symbolic of our tradition and history and therefore the foundation on which to build; kinara (candleholder), symbolic of ancestral roots, our parent people, Continental Africans; muhindi (corn), symbolic of children and the future of African people which they embody; kikombe cha umoja (unity cup), symbolic of the foundational principle and practice of unity which makes all else possible; and zawadi (gifts), symbolic of the labor and love of parents and the commitments made and kept by the children. There are also two supplemental symbols: a representation of the Nguzo Saba and the bendera (flag), containing the three colors black, red and green, symbolic of African people, the struggle, and the promise and future that come from the struggle respectively.

A central and culminating event is the gathering of the community on December 31 for an African karamu (feast) featuring libation and other ceremonies of honoring the ancestors and narratives, poetry, music, dance and other performances to celebrate the goodness of life, relationships and cultural grounding. Kwanzaa ends on January 1 with the Siku ya Taamuli (Day of Meditation) which is dedicated to sober self-assessment and recommitment to the Nguzo Saba and all those other African values which reaffirm commitment to the dignity and rights of the human person, the well being of family and community, the integrity and value of the environment and the reciprocal solidarity and common interests of humanity.

III. Songs That Speaks to the Moment

Nguzo Saba Song

Leader: I said Umoja

Group: I said Umoja

Leader: Means unity

Group: It means unity

Leader: I said Kujichagulia

Group: Kujichagulia

Leader: Means Self-determination

Group: It means Self-determination

Leader: I said Ujima

Group: I said Ujima

Leader: Means Collective Work and Responsibility

Group: It means Collective Work and Responsibility

Leader: I said Ujamaa

Group: I said Ujamaa

Leader: Means Cooperative Economics

Group: It means Cooperative Economics

Leader: I said Nia

Group: I said Nia

Leader: Means Purpose

Group: It means Purpose

Leader: I said Kuumba

Group: I said Kuumba

Leader: Means Creativity

Group: It means Creativity

Leader: I said Imani

Group: I said Imani

Leader: It means faith in all of our people

Group: It means faith in all of our people

(Leader: It means faith in all of our teachers)

(Group: It means faith in all of our teachers)

(Leader: It means faith in all of our leaders)

(Group: It means faith in all of our leaders)

Leader: Nguzo Saba

Group: Nguzo Saba

Leader: The Seven Principles

Group: The Seven Principles

Leader and Group: Sing last stanza two more times, each time getting quieter and quieter, until gradually fading out.

Dr. Bernice Johnson Reagon, a member of The African American Lectionary cultural resource team, wrote the song “Seven Principles” to express her understanding of the Nguzo Saba.

Seven Principles

1. Umoja -- Unity that brings us together (3x)

2. Kujichagulia -- Kujichagulia – Kujichagulia

Kujichagulia (5x) (chant beginning with the third Kujichagulia) We will determine who we are! (3x)

3. Ujima – Working and building our union (3x)

4. Ujamaa – We’ll spend our money wisely (3x)

5. Nia – We know the purpose of our lives (3x)

6. Kuumba – All that we touch is more beautiful (3x)

7. Imani – We believe that we can! We know that we can! We will any way – that we can!!!

IV. A Cultural Response

I created Kwanzaa in the context of the Black Freedom Movement, and thus it reflects a vision and values deemed necessary and important to the success of that struggle and the enhancement of black life. In the Movement, there were two main areas of emphasis—reaffirmation of our Africanness and our social justice tradition. The Civil Rights phase of the Black Freedom Movement stressed social justice and the Black Power phase added re-Africanization.

Out of this process emerged what was called efforts to “return to the source” or more basic to get “Back to Black” and bring forth the best ideas and practices from our own culture, ancient and modern. From this emphasis emerged the Black Power Movement shaping the development of modern Black Arts, Black Studies and Black liberation theology movements as well as Kwanzaa, and initiatives in recovering African names, values, life-cycle ceremonies and other cultural practices. I was at UCLA working on my doctorate in political science when the Black Power phase of the Black Freedom Movement emerged. I left to work in the Movement and did not return to the university to finish my doctorate until 1975.

Indeed, when I left the university, it was a response to the challenge deeply rooted in our culture since the earliest of times, to acquire and use knowledge in the interest of bringing, increasing and sustaining good in the world. In our culture as African people, whether we read the texts of ancient Egypt or Anna Julia Cooper, Mary McLeod Bethune, W. E. B. DuBois or Benjamin Mays, knowledge is never for knowledge sake, but always for human sake. Thus, we must not only know but also act in the interest of good in the world. We sum up our duty in Kawaida philosophy this way: “to know our past and honor it; to engage our present and improve it and to imagine our future and forge it in good and expansive ways.”

Thus in this tradition and context, I created Kwanzaa for three basic reasons. First, I created Kwanzaa to reaffirm our rootedness as African people, in African culture—ancient and modern, for we had been lifted out and had lost so much of this culture through and in the Holocaust of enslavement. Second, I created Kwanzaa to give us as African people a special time when we could come together all over the world, reaffirm the bonds between us and meditate on the awesome meaning of being African in the world. Today, over 40 million Africans each year on every continent in the world and throughout the world’s African communities celebrate this holiday, themselves and their culture. Finally, I created Kwanzaa to introduce and reinforce the importance of African communitarian values; values that stress and strengthen family, community and culture. And, of course, the central communitarian values of Kwanzaa, the cultural hub and hinge on which the holiday turns are the Nguzo Saba, the Seven Principles.

People always ask, did I ever imagine the holiday would grow so quickly and spread so widely. My response is always in three parts. First, I say clearly I could not predict the future and so I had no idea how it would develop. But I had faith. A shared faith with members of my organization Us, that if I created something of real and lasting value and we taught it patiently and respectfully to our people, they would see its value, embrace it and use it to enrich and expand their lives. Secondly, I give honor to those who made me and the holiday possible. For in African tradition, we never claim exclusive credit for anything. For all that we are and do are enriched and made real and good by those who touch our lives and share good with us.

So, I am thankful to my father and mother who brought me into being and taught me a righteous way to walk in the world; my sisters and brothers and whole family who nurtured and sustained me, and especially my wife, Tiamoyo, who inspires and assists me in all things good and beautiful; the members of Us, the founding organization of Kwanzaa, who first practiced it and who are an indispensable source of intellectual exchange and collegial support; my friends and supporters around the world; and the people of the Movement who helped take it around the country and the world. And, of course, I am thankful to all African people who saw in Kwanzaa a message and meaning of profound value and embraced it and practiced it; and to our ancestors who gave us this ancient, great and varied culture we call African with its rich and limitless resources from which we can and do draw daily to understand, enrich and expand our lives.

Finally, I always note that I feel blessed to have seen an important part of my life’s work come to fruit and flourish in my lifetime. And I’m especially grateful when I think of how those greater and more worthy than I were not able to see their work bear fruit and flourish in a similar way. But I gain a sense of satisfaction in knowing that whatever I’ve incorporated in Kwanzaa and Kawaida philosophy based on their lives and teachings has made my work worthy and possible and thus their work hopefully is rightfully honored and continued in my own.

V. Making It a Memorable Learning Movement

The celebration of Kwanzaa is organized around five fundamental kinds of activities rooted in the ancient first-fruit harvest celebration. First, Kwanzaa, like the ancient harvest celebrations, is a time for ingathering of the people to reaffirm the bonds between us, as persons, families, community and a people. It is a time to celebrate the joy and rightness of being together, of sharing good, and of cultivating and sustaining righteous relations at every level and in every form.

- Strengthen Community and Family:

Some Specific Activities:

(a) visit and share with relatives and friends;

(b) hold community events of reaffirmation and unity;

(c) visit the ill and aged reaffirming their meaning to us as a community; and

(d) reconcile, where possible, with those from whom we’ve become alienated even if it's difficult.

- Reverence the Creator and Creation: Kwanzaa, like the ancient celebrations is a time of special reverence for the Creator and creation, a special time of giving thanks for the harvest of good in our lives, the good given and the good received. It is a special time to reaffirm our recognition of the world as sacred space, reaffirm our sense of oneness in it and our responsibility to care for and preserve it.

Some Specific Activities:

(a) collect and distribute items for the needy;

(b) do environmentally friendly things in a more conscious and intensified way; and

(c) give lectures, and hold forums on the environment, its meaning, value and our relationship to it.

- Commemorate: Kwanzaa is a time for commemoration of the past, a time to remember, teach and reflect on the rich and limitless lessons of our life and history as a people. It is a time to raise up and praise the ancestors and honor our elders. For as we say in Kawaida philosophy, “they are those models of human excellence and achievement who lifted up the light that lasts—the light of the spiritual and the special, the ethical and eternal.” And it is they who taught us to walk as Africans in the world—as bearers of dignity and divinity, as pursuers of excellence, and as creators and sustainers of the good in the world.

Some Specific Activities:

(a) Have ceremonies to pour libation and raise up names;

(b) tell historical narratives of persons and events at meals or special family or community occasions;

(c) honor elders in special ways; and

(d) teach lessons of ancestors and elders in various forums and spaces.

- Recommit: Kwanzaa is a time for recommitment to our highest values, those values which represent and call forth from us the best of what it means to be African and human in the world. It is values that teach us to speak truth, do justice, honor our ancestors and elders, cherish and challenge our children, care for the poor, needy and vulnerable among us, have a rightful relationship with the environment, struggle constantly against evil and always raise up, praise and pursue the good. And, of course, Kwanzaa calls on us to hold fast to and practice daily the Nguzo Saba, the Seven Principles, which are at the heart of the holiday and are life-affirming, life-preserving and life-enhancing.

Some Specific Activities:

(a) organize each day around one of the Seven Principles;

(b) involve children and adults in reciting and explaining its meaning to them and how it affects their lives; and do the same for all Seven Principles;

(c) do art and craft work to illustrate the symbols of the Principles;

(d) hold forums of various kind around discussion and demonstration of the Principles; and

(e) on the last day of Kwanzaa, the Day of Meditation, use the Nguzo Saba as one way to answer the three major questions for meditation: who am I; am I really who I am; and am I all I ought to be? This means measuring ourselves in the mirror of the best of our history and culture and determining where we stand. And it means asking ourselves what is the moral meaning of our lives as Africans in the world; what does it mean to be an African given the ancient and ongoing demands of our history and the current critical challenges of our times.

- Celebrate: Finally, Kwanzaa is a time of celebration of the good, the good of family, community and culture, the good of life, love, friendship, and peace; the good of earth, water and all living things, of field and forest, star and stone, rain and river—in the words of the ancestors, the good of “all that heaven gives, the earth produces, and the waters bring forth from their depths.”

Some Specific Activities:

(a) have forms of good and meaningful celebration: song, poetry, dance, music, story-telling, discussions, meals, recreational activities, etc.; and

(b) of course, hold the community Karamu (Feast of African Food) on December 31 before the Day of Meditation which follows on January 1.

VI. Sources of Gaining and Enhancing Knowledge of Kwanzaa

1. Karenga, Maulana. Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture. Los Angeles, CA: University of Sankore Press, 2008. Online location: www.sankorepress.com accessed 1 August 2009

2. The African American Holiday of Kwanzaa (video), Los Angeles, CA: University of Sankore Press. Online location: www.sankorepress.com accessed 1 August 2009

3. Kwanzaa sets, official symbols and materials available at University of Sankore Press. Online location: www.sankorepress.com accessed 1 August 2009