|

INSTALLATION OF OFFICERS/LEADERS

(AND CELEBRATION OF ALL CHURCH LEADERS)

CULTURAL RESOURCES

(See today’s worship unit for a sample Installation of Officers service.)

Sunday, January 3, 2010

Anthony B. Pinn, Lectionary Team Cultural Resource Commentator

I. Historical Considerations

One of the most significant developments in North America, from the early period of the colonies to the present, has to be the creation and growth of African American religious institutions. And in numerical terms, these institutions are most widely recognizable as black Christian churches in that these churches claim millions of religious African Americans.

Beginning with the hidden corners of African American life, within what we commonly call the “hush arbor” meetings, the black Christian community would gain visibility long before the end of the antebellum period. By the 1750s, for example, there were African American Baptist congregations. In addition, African Americans formed independent Methodist denominations by the early 1800s. And by the early twentieth century, Pentecostal and Holiness churches contributed to the unique religious landscape of African American communities. In more recent decades, the richness of African American organized religion included communities formed around popular figures such as Sweet Daddy Grace (Universal House of Prayer for All People), Father Divine (Peace Mission Movement), James (Prophet) Jones (Church of Universal Triumph, the Dominion of God, Inc.), Dr. Johnnie Coleman (Christ Universal Temple) and a host of others. More recent developments include the use of technology within the context of extremely large and globally embraced, non-denominational churches.

The religious groups and organizations that have marked and continue to inform African American communities represent a wide variety of theological creeds and doctrines, ritual practices, and religious sensibilities. Diversity is the primary marker. However, while differing in terms of beliefs and practices, at least one reality marks all these successful movements and religious communities – strong and visionary leadership.

Beginning during the period of slavery, African American religious communities have relied on the expertise and abilities of “called” leaders to map out and articulate a vision of proper living and productive thinking. Furthermore, religious leaders have given some shape to the struggles for freedom and liberty that mark the United States and have provided inspiration for the hard work done by committed Christians. This is certainly the case with respect to the Civil Rights Movement, but the importance and visibility of strong leadership is not limited to this one example. In large and small ways, people have turned to religious leaders to provide guidance on a variety of issues and topics, assuming these leaders had special abilities that marked them as having responsibilities others could not claim.

While exceptions can always be found, it was widely the case that ministers exercised somewhat singular control as the mark of leadership, and this approach was typically the practice regardless of the particular denomination. The senior minister mapped out the vision for the church and the larger community and determined the strategies to use in promoting the vision. The minister might solicit advice and comments, but it was widely assumed that this person was “called” by God and was positioned to direct conduct in ways not available to the typical member of the laity or the larger community. “Calling” and its ramifications, with respect to assumptions of the pastor’s more insightful read of scripture and special “anointing,” gave a certain type of authority.

As scholars have noted, the late twentieth century entailed an increase in educational opportunities for African Americans, due in large part to the successes of the Civil Rights Movement. African Americans entered universities and professional schools in growing numbers beginning in the 1970s and then brought their education and professional skills to their community engagement and participation in churches. As a consequence, it was no longer safe to assume the minister was the best-informed person in the church. The presence of well educated and highly trained laity forced new models of leadership. And while leadership had been and continues to be a consistent and important factor in the growth of African American religious communities, it is also important to note that the best leaders have had to recognize the need for partnerships and for assistance; and, they have worked to tap the expertise of the congregation.

Shared or communal leadership is now the more typical model utilized in successful churches; and, in this way, senior ministers recognize that the best church work cannot be done in isolation. Instead, the proper leadership structure is a matter of layers and synergy – the combining of expertise and abilities for the good of the community. No one, according to this model, stands alone.

II. Autobiographical Reflection

I am an academic, trained to study, teach, and publish materials related to African American religion(s). And while this work involves some interaction with other academics and with students in the context of the classroom, scholars like me also spend a significant amount of time in isolation working alone in their offices. In this way, we tend to assume control over all aspects of our work in that the academic alone determines what he or she researches and writes. Expertise and authority in this context are understood as limiting the need to ask others, to consult others in any sustained way beyond referencing someone’s work. Even in the classroom, styles of teaching can involve the assumption that the professor knows everything and the student is there to gain knowledge without questioning the authority of the professor.

This arrangement can make for poor leadership strategies during those times when partnership and consensus is necessary. Effective work must involve partnerships, and reflection on the give-and-take of exchange with others. Working together provides a more useful model. My most challenging moments as a scholar, and some of my more rewarding moments, have involved the wisdom offered by others, and the exchange of ideas and thoughts that produced more sustainable and more productive results. Whether studying religion, or ministering to a religious community, shared leadership is a productive strategy.

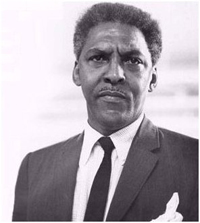

III. Biographical Reflection – Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin (1912-1987) has not received the type of public attention given to figures of the civil right struggle such as Martin Luther King, Jr. However, his importance is undeniable. Rustin understood his role in ways consistent with the strategy of joint effort and shared leadership, that marks the scriptural text for this lectionary moment. He believed in the value of conversation and shared responsibility. Rustin’s work on the freedom rides, the March on Washington, and other civil rights activities mirrors a commitment to synergy as the mark of success as well as mirroring a way of working marked by responsibility for and to others. Bayard Rustin (1912-1987) has not received the type of public attention given to figures of the civil right struggle such as Martin Luther King, Jr. However, his importance is undeniable. Rustin understood his role in ways consistent with the strategy of joint effort and shared leadership, that marks the scriptural text for this lectionary moment. He believed in the value of conversation and shared responsibility. Rustin’s work on the freedom rides, the March on Washington, and other civil rights activities mirrors a commitment to synergy as the mark of success as well as mirroring a way of working marked by responsibility for and to others.

Having travelled to India and gained knowledge of non-violent direct action, Rustin played a significant role in establishing the protest strategies that would define civil rights struggles – strategies that, at their best, relied on the power of people united under a shared vision and cause. He pushed for partnerships between the civil rights movement and other organizations concerned with better life options in the United States. This entailed yet another demonstration of his commitment to cooperation.

IV. Songs that Speak to the Moment

Walk Together Children

Working in isolation, attempting to live a proper and productive life without partnerships and without the support of others, is a difficult position that often results in less than ideal results. It is important to join forces with others who have similar commitments, to, as the song suggests, “walk” together. The key is the recognition of community, shared accountability.

Walk together children

Don' you get weary

Walk together children

Don't you get weary

Oh, talk together children

Don't you get weary

There's a great camp meeting in the promised land

Sing together children

Don' you get weary

Sing together children

Don't you get weary

Oh, shout together children

Don't you get weary

There's a great camp meeting in the promised land

Gwineter mourn and never tire

Mourn and never tire

Mourn and never tire

There's a great camp meeting in the Promised Land.1

We All Can Do Good

As the scripture for this day suggests, we have an obligation to work mindful of others, and thereby recognize the need to help others. It is in this way we are able to share responsibility for promoting the best of the gospel tradition. Leaders installed and recognized on this day must be mindful of their need to work in cooperation with others, to always remember the benefits of partnership, and to always promote the welfare of others.

Our lives, we are told, are but fleeting at best,

Like roses they fade and decay;

Then let us do good while the present is ours,

Be useful as long as we stay.

Do good unto others, do good while we can,

Our moments how quickly they fly;

Remember the proverb, remember it now,

We all can do good if we try.

A look or a smile, that in kindness we give,

May comfort a desolate heart;

May sweeten a life that is lonely and sad,

And hope to the weary impart.

How many around us are strangers to God,

How many poor children we see;

If such we could bring to the foot of the cross,

How grateful and glad we should be.

We all can do good, and we all can bestow

Some gift for the sake of the Lord;

If only a cup of cold water we give,

Our souls will not lose their reward.2

V. A Memorable Learning Moment

January 20, 2009 is an important day in the history of leadership in the United States. This is the day when President Obama took the oath of office and, thereby, put into practice much needed changes in the leadership style associated with the top governmental position in the United States.

Thinking back to his campaign, it is safe to say that part of Obama’s appeal was his vision of shared leadership, of the need to communicate and exchange ideas as part of the process of decision making. He inspired citizens of the United States, across racial, social and class lines to embrace him because his style of leadership gave citizens a new sense of involvement – a shared sense of obligation and responsibility. It was this shared accountability that inspired. Feelings of isolation and a sense that public leadership did not understand and did not hear the needs of typical citizens were changed. As President Obama said while campaigning, there is a difference – an important distinction – that should mark a new approach to governmental leadership:

"We're up against the conventional thinking that says your ability to lead as president comes from longevity in Washington or proximity to the White House. But we know that real leadership is about candor and judgment and the ability to rally Americans from all walks of life around a common purpose, a higher purpose."3

This commitment to partnership, to care for the community, was not a simple campaign promise. It has marked his general philosophy as President. He, as we should within our leadership capacities, worked to surround himself with knowledgeable people, and seems to value and utilize their expertise. Isn’t this the way church leadership should function? Ministers, like President Obama, should not feel threatened by the talents of others but should see these talents as important, as invaluable. Inviting assistance is not a sign of weakness or inability. Rather, it is a sign of mature thinking and a commitment that extends beyond individualism and self-promotion. Working together through leadership that involves a shared commitment makes communities stronger. Effective leadership is shared leadership. Compassion for others is the mark of community sustainability and serves as the best way to build worlds that represent the best of all of our abilities and vision.

VI. Learning More about this Moment

Books

Andrews, Dale. Practical Theology for the Black Church. Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox, 2002.

Fluker, Walter. Ethical Leadership: The Quest for Character, Civility and Community.

Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2009.

Fluker, Walter, Ed. The Stones that the Builder Rejected: The Development of

Ethical Leadership from the Black Church Tradition. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity

Press International, 1998.

Franklin, Robert. Crisis in the Village: Restoring Hope in African American

Communities. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2007.

Gilkes, Cheryl Townsend. If It Wasn’t for the Women…Black Women’s Experience and

Womanist Culture in Church and Community. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2000.

Tribble, Jeffries. Transformative Pastoral Leadership in the Black Church. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Notes

1. “Walk Together Children.” Online location: http://www.negrospirituals.com/news-song/walk_together_children.htm accessed 12 October 2009

2. “We All Can Do Good.” Online location: http://www.allgospellyrics.com/ accessed 12 October 2009

3. Barack Obama speech: “Yes, We Can Change.” Online location: http://www.cnn.com/2008/POLITICS/01/26/obama.transcript/index.html accessed 12 October 2009

|