Cultural Resources

CHOIR ANNIVERSARY

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Sunday, August 9, 2009

Mellonee Burnim, Guest Cultural Resource Commentator

Associate Professor in the Department of Folklore and Ethnomusicology Indiana

University, Bloomington, IN

I. Historical Background

Music has always played a central role in African American worship. The songs sung by slaves belonged to no single individual, for they represented the collective experience and voice of the community at large. There were no rehearsals, for the songs were communally composed and orally transmitted. They were fixed in neither time nor space. The congregation and the choir were one and the same.

When choral singing was first introduced into worship services in Philadelphia’s Bethel African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church between 1841 and 1842, older members of the congregation protested vehemently, considering the practice as bringing “the devil into the church.”1 Rather than support this musical innovation, some disgruntled members chose to sever their ties to the church. By 1888, less than half a century later, Daniel Alexander Payne, an A.M.E. bishop, noted that the opposition to choral singing had been quelled, and “every Church in the Connection [sought] to have a good choir.”2

The choir in the majority of present-day African American churches of all denominations is an integral and defining component of the worship experience. The choir anniversary is both a formal and public celebration of this fact, and a way of honoring the significance of music and those dedicated to bringing music to life on Sunday morning and at many other times when the need arises.

The choir in traditional African American worship services functions in a number of different ways. Indicative of the significance of these multiple roles, leaders of churches, pastors in particular, are known to seek musicians of the highest caliber to lead the choir—musicians with demonstrated skill as singers and/or keyboard players, as well as that of directing. Good choirs are highly valued for their role in introducing new repertoire to the congregation, energizing worship, reinforcing sermon content, supporting the pastor’s travels to other churches for guest appearances, and even contributing to overall church efforts to attract and maintain members.

Traditional African American worship services are filled with music, typically with several selections offered by one or more choirs each Sunday. Before the advent of the gospel choir in the 1930s, the senior choir with its repertoire of hymns, spirituals and songs from Western European classical repertoire was predominant in some worship services. Today’s youth choir was the junior choir of days gone by. Various other choral aggregates are now commonplace, even in churches of modest size—men’s choir, women’s choir, children’s choir and also the mass choir, which combines all existing choral units into a whole.

Choir anniversary is a time for affirmation, renewal, and reflection. It is a time to

celebrate the transforming and healing and power of music, its centrality to the worship service, and the expectation that all musicians, vocal and instrumental, young and old, express their music as Christian witness.

The choir anniversary is sometimes celebrated as a multiple day event. Pre-anniversary services are solely devoted to music provided by guest choirs, soloists and ensembles from other churches, communities or cities, while the actual anniversary service exclusively features the designated choir. Programmatic changes may occur from year to year or from one context to another; however, the raison d’être for the anniversary itself remains the same--the choir and the music it provides are central to the African American worship experience. As a singing people, African Americans have witnessed the power of music throughout our history in this nation. The choir anniversary is a time of rededication, consecration and commitment—a time to celebrate our God, and our faith.

II. A Famous Music Leader

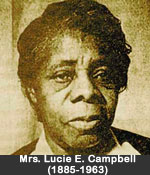

As a pioneering figure in the development of gospel music, Lucie Campbell is noted for her forty-plus years as Director of Music for the Christian Education Department of the National Baptist Convention, U.S.A Inc., (NBC) which, at her death, was the largest aggregate of African American Christians in the United States. Ms. Campbell composed more than 100 songs, directed 1000 voice choirs at the National Baptist Convention, and served as the only female member of the NBC Sunday School Publishing Board which released the landmark Gospel Pearls collection of African American religious music favorites in 1921.3 One of my favorite songs that she wrote is “Touch Me Lord Jesus.”

As a pioneering figure in the development of gospel music, Lucie Campbell is noted for her forty-plus years as Director of Music for the Christian Education Department of the National Baptist Convention, U.S.A Inc., (NBC) which, at her death, was the largest aggregate of African American Christians in the United States. Ms. Campbell composed more than 100 songs, directed 1000 voice choirs at the National Baptist Convention, and served as the only female member of the NBC Sunday School Publishing Board which released the landmark Gospel Pearls collection of African American religious music favorites in 1921.3 One of my favorite songs that she wrote is “Touch Me Lord Jesus.”

Touch Me Lord Jesus

Touch, touch me Lord Jesus, with thy hand of mercy.

Make each throbbing hear-beat feel thy pow’r divine.

Take my will forever, I will doubt thee never.

O Lord, please cleanse me, my dear Savior,

Make me wholly thine.4

III. Poetry and the Legacy of Music in the Lives of African Americans

(A) Chronicling the genius of slaves in creating the spiritual, the following excerpt from James Weldon Johnson’s poem, O Black And Unknown Bards, reminds us of the historical legacy of music in the lives of African Americans—its substance, its poignancy, its spiritual and cultural meaning.

O Black And Unknown Bards

O Black and unknown bards of long ago,

How came your lips to touch the sacred fire?

How, in your darkness, did you come to know

The power and beauty of the minstrels’ lyre?

Who first from midst his bonds lifted his eyes?

Who first from out the still watch, lone and long,

Feeling the ancient faith of prophets rise

Within his dark-kept soul, burst into song?

Heart of what slave poured out such melody

As “Steal away to Jesus”? On its strains

His spirit must have nightly floated free,

Though still about his hands he felt his chains.

Who heard great “Jordan roll”? Whose starward eye

Saw chariot “swing low”? And who was he

That breathed that comforting, melodic sigh,

“Nobody knows de trouble I see”?

There is a wide, wide wonder in it all,

That from degraded rest and servile toil

The fiery spirit of the seer should call

These simple children of the sun and soil,

O black slave singers, gone, forgot, unfamed,

You—you alone, of all the long, long line

Of those who’ve sung untaught, unknown, unnamed

Have stretched out upward, seeking the divine.5

(B) Throughout our history in these United States, African American poets have turned to music as a subject of inspiration, and as an affirmation of its status as uniquely and unequivocally American. The poem, Negro Spiritual, by Perient Trott makes this clear.

Negro Spiritual

Sable is my throat

golden the cable

golden the column of its sound—

firm, my transplanted feet

upon this soil—

deep, my roots

I am the sounding board

the maker of songs—

mine, the folk song of America!

sensitive, my transplanted feet

to the rhythm of the earth:

deep, my roots

in the somnambulant greatness

of the earth

in the nostalgia

of my race

in the drama

of my people

uprooted

dispossessed

transplanted—

the song of America

wells full-bodied

in my throat…

I am the maker of songs

The voice of colony

The folk song of empire

O, sable is my throat….

golden, the rich cable….

rich, the column of my song!

Sable, sable!

Golden, golden!

O sable is my throat!6

IV. Traditional Songs

In the song “I’m Gonna Sing,” the three repeated lines of text “I’m gonna sing when the Spirit says a-Sing,” followed by a recurring fourth line helps to identify this song as a spiritual. By changing only one word in the introductory line, new verses can be created infinitely, thereby facilitating its oral transmission and inviting the full participation of every one present. References to the Holy Spirit in the text attest to the widely held African American premise that music can and must be an expression of the heart.

I’m Gonna Sing

I’m gonna sing when the Spirit says a-Sing,

I’m gonna sing when the Spirit says a-Sing,

I’m gonna sing when the Spirit says a-Sing,

And obey the Spirit of the Lord.

2. shout 3. preach 4. pray. 7

Utilizing the same AAAB form identified in the spiritual above, “Over My Head” links the expression of music with the presence of God, affirming the significance of music in African American worship, and its power to engage, exhilarate, and even challenge those who surrender to its power.

Over My Head

Over my head I hear music in the air.

Over my head I hear music in the air.

Over my head I hear music in the air.

There must be a God somewhere.

Over my head I hear singing in the air.

Over my head I hear singing in the air.

Over my head I hear singing in the air.

There must be a God somewhere.

Over my head I see Jesus in the air. (3X)

There must be a God somewhere.8

V. Modern Songs

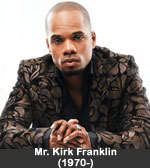

The signature song of performer composer Kirk Franklin’s debut release Kirk Franklin And the Family in 1993, “Why We Sing,” launched his rapid rise to popularity and multi-platinum sales. Although he was only twenty-three years old at his debut, “Why We Sing” became an interdenominational anthem among African American churches across the nation, and won Stellar Awards from the black gospel music industry, Dove Awards from the predominantly white Gospel Music Association, and the James Cleveland Gospel Music Work shop of America (GMWA) Excellence Award. Inspired by the text of the chorus of the hymn “His Eye Is on the Sparrow” (1905) by Civilla Martin and Charles Gabriel, Franklin’s composition speaks directly to the aesthetic sensibilities of African American worshippers, for whom outward demonstration of religious fervor and commitment are a welcome and time honored tradition.

The signature song of performer composer Kirk Franklin’s debut release Kirk Franklin And the Family in 1993, “Why We Sing,” launched his rapid rise to popularity and multi-platinum sales. Although he was only twenty-three years old at his debut, “Why We Sing” became an interdenominational anthem among African American churches across the nation, and won Stellar Awards from the black gospel music industry, Dove Awards from the predominantly white Gospel Music Association, and the James Cleveland Gospel Music Work shop of America (GMWA) Excellence Award. Inspired by the text of the chorus of the hymn “His Eye Is on the Sparrow” (1905) by Civilla Martin and Charles Gabriel, Franklin’s composition speaks directly to the aesthetic sensibilities of African American worshippers, for whom outward demonstration of religious fervor and commitment are a welcome and time honored tradition.

Why We Sing

Verse

Someone asked the question: why do we sing?

When we lift our hand to Jesus, what do we really mean?

Someone may be wond’ring: when we sing our song

At times we may be crying and nothings even wrong.

Refrain

I sing because I’m happy. I sing because I’m free.

His eye is on the sparrow, that’s the reason why I sing.

Glory, hallelujah! You’re the reason why I sing.

Verse

When the song is over, we all say “Amen.”

In our heart just keep on singing, and the song will never end.

If somebody asks you: was it just a show?

Lift your hands and be a witness and tell the whole world, “No.”

Refrain

I sing because I’m happy. I sing because I’m free.

His eye is on the sparrow, that’s the reason why I sing.

Glory, hallelujah! You’re the reason why I sing.

Verse

When we cross the river, we’ll study war no more.

We will sing our song to Jesus, the One whom we adore.

Refrain

I sing because I’m happy. I sing because I’m free.

His eye is on the sparrow, that’s the reason why I sing.

Glory, hallelujah! You’re the reason why I sing.9

The daughter of a Baptist minister, Los Angeles resident Margaret Douroux developed a love for gospel music as she served as accompanist for choirs in her father’s church from the time she was a young girl. A highly respected and sought after composer, her works have been sung and recorded by such major gospel artists as the Reverend James Cleveland, Shirley Caesar, Helen Baylor and the Sounds of Blackness. During the 1970s, her “Give Me a Clean Heart” became a national standard in African American churches of all denominations. Its inclusion in the New National Baptist Hymnal, and the African American Heritage Hymnal, and the Songs of Zion, the African American Supplement to the United Methodist Hymnal, among other sources, attests to the enduring legacy of this work.10

The daughter of a Baptist minister, Los Angeles resident Margaret Douroux developed a love for gospel music as she served as accompanist for choirs in her father’s church from the time she was a young girl. A highly respected and sought after composer, her works have been sung and recorded by such major gospel artists as the Reverend James Cleveland, Shirley Caesar, Helen Baylor and the Sounds of Blackness. During the 1970s, her “Give Me a Clean Heart” became a national standard in African American churches of all denominations. Its inclusion in the New National Baptist Hymnal, and the African American Heritage Hymnal, and the Songs of Zion, the African American Supplement to the United Methodist Hymnal, among other sources, attests to the enduring legacy of this work.10

Give Me a Clean Heart

Refrain

Give me a clean heart so I may serve thee.

Lord, fix my heart so that I may be used by thee.

For I’m not worthy of all these blessings,

Give me a clean heart, and I’ll follow thee.

Verses

I’m not asking for the riches of the land.

I’m not asking for the proud to know my name.

Please give me, Lord, a clean heart, that I may follow thee.

Give me a clean heart and I’ll follow thee.

Sometimes I am up and sometimes I am down.

Sometimes I am almost level to the ground.

Please give me, Lord, a clean heart, that I may follow thee.

Give me a clean heart and I’ll follow thee.

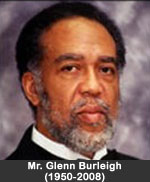

A native of Oklahoma and an Oklahoma University alum, composer-pianist Glenn Burleigh is best known for his composition “Order My Steps,” (1991) the premier track on Women of Worship, the debut release of the Women’s Division of the James Cleveland Gospel Music Workshop of America. Referring to himself as both a minister of music and “the word,” Burleigh’s texts are strongly linked to Scripture, as illustrated in “Order My Steps” based on Psalm 119:133, whose message calls for personal humility, God’s guidance and the anointing of the Holy Spirit in singing songs for worship.

A native of Oklahoma and an Oklahoma University alum, composer-pianist Glenn Burleigh is best known for his composition “Order My Steps,” (1991) the premier track on Women of Worship, the debut release of the Women’s Division of the James Cleveland Gospel Music Workshop of America. Referring to himself as both a minister of music and “the word,” Burleigh’s texts are strongly linked to Scripture, as illustrated in “Order My Steps” based on Psalm 119:133, whose message calls for personal humility, God’s guidance and the anointing of the Holy Spirit in singing songs for worship.

Order My Steps

Verse1

Order my steps in your word, dear Lord,

Lead me, guide me, every day.

Send your anointing, Father, I pray.

Order my steps in your word.

Please, order my steps in your word.

Verse 2

Humbly I ask thee, teach me your will.

While you are working, help me be still.

Though Satan is busy, God is real!

Order my steps in your word.

Please, order my steps in your word.

Verse 3

Bridle my tongue, let my words edify,

Let the words of my mouth be acceptable in thy sight.

Take charge of my thoughts, both day and night.

Order my steps in your word.

Please, order my steps in your word.

I want to walk worthy, my calling to fulfill.

Please order my steps, Lord, and I’ll do your blessed will.

The world is ever changing, but you are still the same.

If you order my steps, I’ll praise your name.

Order my steps, in your word.

Order my tongue, in your word.

Guide my feet, in your word.

Wash my heart, in your word.

Show me how to walk, in your word.

Show me how to talk, in your word.

When I need a brand new song to sing,

Show me how to let your praises ring.

In Your word! In your word!

Order my steps in your word.

Please, order my steps in your word.11

III. Suggested Reading and Websites List Developed by Alfie Wines

Abbington, James. African American Church Music Series.http://www.giamusic.com/choral_music/african_american.cfm

This is a choral music series in the tradition of the music of the African American church.

Abbington, James. Let Mt. Zion Rejoice!: Music in the African American Church.

This book addresses many practical aspects of music of the African American church, including the relationship between the pastor and the music staff.

African American Heritage Hymnal. Chicago, IL: GIA Publications, Inc., 2001.

African American Worship: Faith Looking Forward The Journal of the

This journal contains essays on various topics related to African American sacred music.

Black Sacred Music—A Journal of Theomusicology. Durham, NC: Duke University

This journal also contains essays on various topics related to Black sacred music.

Costen, Melva Wilson. African American Christian Worship. Updated Edition.

This book helps the reader understand the history and the contemporary context of African American worship.

Costen, Melva Wilson and Darius I. Swann. The Black Christian Worship Experience.

This book provides insight into the total Black Worship experience.

Lining Out the Word:--Dr. Watts Hymn Singing in the Music of

This book provides insight into the tradition of the lined hymn.

Floyd, Samuel A. The Power of Black Music—Interpreting Its History from Africa to

This book traces the history of Black Music from its African roots to contemporary contexts.

Holmes, Barbara A. Joy Unspeakable—Contemplative Practices of the Black Church.

This book debunks notions that worship in the Black Church is not contemplative.

Jones, Ferdinand and Arthur Jones. The Triumph of the Soul: Cultural and

This book explores African American music from a cultural and psychological point of view.

Kirk-Duggan, Cheryl. Exorcizing Evil—A Womanist Perspective on the Spirituals.

This book explores African American spirituals from the perspective of the Black woman.

Lovell, John. Black Song—The Forge and the Flame—The Story of How the Afro-

This book provides important insights into the making of the spiritual.

Mapson, J. Wendell Jr. The Ministry of Music in the Black Church. Valley Forge, PA:

This book explores the contemporary challenges facing music ministry in the Black Church.

McClain, William B. Come Sunday—The Liturgy of Zion—A Companion to Songs of

This book provides liturgy that can be used in conjunction with many of the songs in Songs of Zion.

Songs of Zion.

This songbook, published by the United Methodist Church, includes many traditional songs of the black church. Summary notes on history, style and performance notes are also included.

Soul Praise—Amazing Stories and Insights Behind the Great African-American Hymns

This book tells the story behind many of the beloved songs of the African American Church.

Southern, Eileen. The Music of Black Americans—A History. New York, NY: Norton,

This book explores the music of black Americans from a historical viewpoint. Insights in this book can be helpful in understanding the music of the Black Church as well.

Southern, Eileen, ed. Readings in Black American Music. New York, NY: W. W.

This is a book of essays on Black American music.

This Far By Faith: American Black Worship and its African Roots. Washington, DC:

Songs in this songbook can be used by any denomination.

Tutu, Desmond. The Worshipping Church in Africa. Durham, NC: Duke University

This discussion of worship in Africa helps connect African American worship to its African roots.

Walker, Wyatt Tee. Somebody’s Calling My Name—Black Sacred Music and Social

This book explores the musical genius of the black sacred music and its role in changing the social landscape of African Americans. It encourages the black Church to keep its rich musical heritage alive.

Warrick, Mancel, Joan R. Hillsman, and Anthony Manno. The Progress of Gospel

This book looks at gospel music from a historical perspective.

Warren, Gwendolyn Sims. Ev’ry Time I Feel the Spirit—101 Best-Loved Psalms,

This book tells the story behind many songs of the African American church.

Ward, Andrew. Dark Midnight When I Rise—The Story of the Fisk Jubilee Singers—

This book covers the history of the Fisk Jubilee Singers from 1851-1903. It provides important insight for understanding this musical genre and its impact on the world.

Watkins, Ralph C. The Gospel Remix—Reaching the Hip Hop Generation. Valley

This book explores the role of gospel hip hop in reaching young people for Jesus Christ.

Zion Still Sings—For Every Generation. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 2007.

New songs and styles are included.

Notable Websites

- The African American Lectionary. Online location:

http://www.TheAfricanAmericanLectionary.org accessed 12 Feb. 2009

In addition to this material, view other Year Two material and, particularly view the entire Year One calendar by visiting the archive link for each area.

- This website has the transcript and video for the PBS segment “Black church Music,” broadcast on April 13, 2007. Online location: http://www.pbs.org/ accessed 12 Feb. 2009

- Emmett G. Price III. Online location:

http://www.emmettprice.com/biography.html accessed 12 Feb. 2009

This website hosted by Dr. Emmett Price, III lists a variety of information that would be of interest to persons who want to know more about black church music.

- Emmanuel Research Review. Online location:

http://www.egc.org/research/issue_17.htm accessed 12 Feb. 2009

This website includes information regarding The Black Church Music Ministry Project (BCMMP) which is located in Boston, MA.

Notes

1. Payne, Daniel Alexander, Sarah C. Bierce Scarborough, and C. S. Smith. Recollections of Seventy Years. Nashville, TN: Pub. House of the A.M.E. Sunday School Union, 1888. p. 235; Recollections of Seventy Years: Electronic Edition. Online location: http://docsouth.unc.edu/church/payne70/payne.html accessed 12 Feb. 2009

2. Ibid.

3. Burnim, Mellonee V., and Portia K. Maultsby. African American Music: An Introduction. New York, NY: Routledge, 2006. pp. 493-508.

4. African American Heritage Hymnal. Chicago, IL: GIA Publications, 2001. #274; The New National Baptist Hymnal 21st Century Edition. Nashville, TN: Triad Publications, 2005. #336

5. Hughes, Langston, and Arna Wendell Bontemps. The Poetry of the Negro, 1746-1970. 1949. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1970.

6. Ibid.

7. “I’m Gonna Sing.” Traditional. Cleveland, J. Jefferson, and Verolga Nix. Songs of Zion. Supplemental worship resources, 12. Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 1981. #81

8. Ibid.

9. African American Heritage Hymnal. #496

10. “About Dr. Margaret Pleasant Douroux, CEO/Founder, Heritage Music Foundation.” African American Heritage Hymnal.#461

11. African American Heritage Hymnal. #333