Cultural Resources

ELECTION DAY

CULTURAL RESOURCES

*(This material may also be used on the Sunday preceding Election Day.)

Tuesday, November 4, 2008

William H. Wiggins, Jr., Lectionary Team Cultural Resources Commentator

I. Introduction

Keep the black man from the ballot and we’ll treat him as we please, with no means for protection, we will rule with perfect ease.

— Lizelia Augusta Jenkins Moorer1

Our two scriptures for Election Day, Matthew 22:15-22 and Mark 12:13-17, explore the eternal issue of the proper relationship between the Christian community and the secular government under whose laws they reside. The Pharisees raise this issue when they ask Jesus: “Tell us, then, what you think. Is it lawful to pay taxes to the emperor or not?” (Matthew 22:17); and “Is it lawful to pay taxes to the emperor, or not? Should we pay them, or should we not?” (Mark 12:14-15) Jesus answer, “Give therefore to the emperor the things that are the emperor’s and to God the things that are God’s,” (Matthew 22: 21 and Mark 12:17), is a resounding yes; you should pay your taxes. In sum, Christians have abiding civic as well as religious responsibilities. The paying of taxes is a civic responsibility that Christians have, and the following of the Church’s moral and ethical teachings are religious responsibilities to which Christians must adhere.

The right to vote has been one civic responsibility that African Americans have struggled to freely exercise since Emancipation. Numerous historical documents serve as road signs of progress that our ancestors have made toward exercising the right to vote and run for Federal, state and municipal offices, as freely as any of our fellow American citizens.

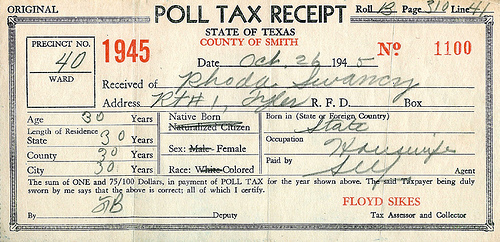

II. The Poll Tax

Their struggles even produced Amendments to the United State Constitution. For example, the Twenty Fourth Amendment, which was ratified on January 23, 1964, speaks directly to the issue of the abolition of poll taxes, a device used by many southern states to disenfranchise African American voters after Reconstruction.

On March 24, 1965, Roy Wilkins, the Executive Director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, testified before House Subcommittee No. 5 of the Committee of the Judiciary and shared with the panel the crippling effect of the poll tax through details that Dr. Aaron Henry, the President of the Mississippi Branch of the NAACP, had told to him:

The poll tax is a great deterrent to voting in Mississippi. It must be paid on or before the first day of February in the year that one intends to vote. A voter must pay the tax for two years before he can vote. You cannot pay back taxes. During the month of January we are at our peak in unemployment. This is the most likely time of the year not to have the $3 necessary to pay the poll tax in Coahoma County (in many counties the tax is $2 but in Coahoma County it is $3). Our experience here in Coahoma is that one cannot pay taxes for another except in the immediate family. A man may pay the poll tax for his wife or she for him but not for one living in the household.2

Evelyn T. Butts (standing)

Her attorney Joseph Jordan (seated)

One person who was influential in bringing an end to the Poll Tax was Evelyn T. Butts. Butts was born May 22, 1924. She was the second of six children. Her father was a laborer and, when she turned ten, her mother died. When she filed her suit against poll taxes, Mrs. Butts was an unemployed seamstress and her husband was a disabled veteran. The poll tax to vote in Virginia was $1.50. Butts disagreed with the tax and, in October1965, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear Butts’ appeal as she lost her case in the lower courts. Her attorney, Joseph A. Jordan, Jr., argued the case with U.S. Solicitor General Thurgood Marshall who later became a U.S. Supreme Court justice. The Supreme Court eliminated the Poll Tax in March 1966, two and a half years after Butts sued. After the decision Butts said, “The victory was an accomplishment for blacks and whites who could not afford to pay the tax.”3

Butts later became active in numerous civic, community, and political organizations. Following the decision, she set about registering many blacks - 2,882 in one six-month period. Butts received dozens of awards for her service. Among her many accomplishments was her appointment to the Norfolk Redevelopment and Housing Authority in 1975. Mrs. Butts died in 1993 and, in 1995, had a street named in her honor in Norfolk.4

Ultimately, the 24th Amendment was passed ending poll taxes and other tools used to disenfranchise African American voters such as literacy tests. The amendment reads:

Section 1. The right of citizens of the United States to vote in any primary or other election for President or Vice President, or electors for President or Vice President, or for Senator or Representative in Congress, shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State by reason of failure to pay any poll tax or other tax.

Section 2. The Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.5

III. Librarian Terrye Conroy Gives the History on Blacks and Voting

Terrye Conroy is a reference librarian for the Law Library of the University of South Carolina. In 2005, she developed a reference guide titled “The Promise of Voter Equality: Examining the Voting Rights Act at 40” for a symposium held at the University of South Carolina School of Law in 2005. The guide became a bibliography.

Conroy writes concerning black and voting:

The Civil Rights Acts of 1957, 1960, and 1964 empowered the U.S. Department of Justice to investigate and litigate voting rights violations; however, enforcement on a case-by-case basis proved time-consuming and ineffective. Voter registration drives were often met with violence. When student volunteers from around the country gathered in Mississippi for Freedom Summer in 1964, Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner were arrested and handed over to be murdered by Ku Klux Klan members. After Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot and killed by Alabama State Troopers while protecting his grandmother from being beaten during a voter registration march in Marion, Alabama, Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference decided to organize a protest march from nearby Selma to the state capitol in Montgomery. On March 7, 1965, state troopers led by Sheriff Jim Clark trampled marchers with their horses and attacked them with whips, clubs, and tear gas as they attempted to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge. ABC News interrupted its broadcast of the movie Judgment at Nuremburg as Americans watched in horror the events of what was to become known as “Bloody Sunday.” John Lewis, at the time a young leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and since 1986 congressman for Georgia’s Fifth Congressional District, suffered a concussion when attacked while leading the march…

As he signed the Voting Rights Act into law, President Lyndon B. Johnson described the right to vote as “the most powerful instrument ever devised by man for breaking down injustice and destroying the terrible walls which imprison men because they are different from other men.”6

The Voting Rights Act was signed two years to the month after the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. This law gave the United States Attorney General the power to authorize Federal examiners to see that no African American citizens were denied the right to vote. These responsibilities are spelled out in the first two sections of this law:

Section 2. No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or applied by any State or political subdivision to deny the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.

Section 3. (a)Whenever the Attorney General institutes a proceeding under any statute to enforce the guarantees of the fifteenth amendment in any State or political subdivision the court shall authorize the appointment of Federal examiners by the United States Civil Service Commission in accordance with section 6 to serve for such period of time and for such political subdivisions as the court shall determine is appropriate to enforce the guarantees of the fifteenth amendment (1) as part of any interlocutory order if the court examines that the appointment of such examiners is necessary to enforce such guarantees or (2) as part of any final judgment if the court finds that violations of the fifteenth amendment justifying equitable relief have occurred in such State or subdivision.7

IV. Voting Patterns of African Americans

Until President Franklin D. Roosevelt unveiled his New Deal, “the name given to a sequence of programs he initiated between 1933 and 1938 with the goal of giving work (relief) to the unemployed, reform of business and financial practices, and recovery of the economy during The Great Depression,”8 most African Americans voted overwhelmingly Republican. The shift in the voting preferences can be seen in the U.S. census beginning in the late 1930’s and continuing with the election of John F. Kennedy and the passage of the Voting Rights Act by a Democratic president. Rod Young, in his article on African American voting patterns, indicates that by 1964 eighty-two percent of African Americans voted Democratic, and by 1968 the number was ninety-two percent.9 With the exception of the 1972, 1984, and the 1992 elections, blacks continued to give at least 80% of their collective votes to the Democratic presidential candidate.10

As voter turn-out has steadily declined in the United States, voting by African Americans has also declined. Some have worried that generations who did not participate in the civil rights movement are taking the right to vote, which was earned through marches and even bloodshed, for granted. However, with the presidential candidacy of Senator Barack Obama, Democratic senator from Illinois, voter turn-out by African Americans increased for the 2008 primary election, and many anticipate that this increase will remain during the general election for president.

V. The Loss of Voting Rights by Felons after Release

Little has been said by scholars, politicians or the African American church about the fact that felons in the United States, even after they are released and have paid any applicable fines or restitution, often are never able to vote again in the United States. Given how much is known about disparate sentences given to African Americans compared to Whites, especially for non-violent drug cases, surely the absolute loss of the right to vote deserves to be questioned, if not railed against. John Conyers (Democrat, MI) did introduce the Civic Participation and Rehabilitation Act to regain the right to vote for persons who have served their time in jail or prison. The bill was introduced in 1999, 2003, and 2005 but has not passed.

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, at the end of 2004, 1,469,629 people were incarcerated in this country. According to the Sentencing Project, as of summer 2008, “more than 60% of the people in prison were racial and ethnic minorities.” For Black males in their twenties, one in every eight is in prison or jail on any given day. These trends have been intensified by the disproportionate impact of the “war on drugs,” in which three-fourths of all persons in prison for drug offenses are people of color.”11 Since 1997, nineteen states have amended felony disenfranchisement policies in an effort to reduce their restrictiveness and expand voter eligibility. According to the Sentencing Project, this resulted in 760,000 persons regaining the right to vote.12 However, even with these reforms, an estimated five million (5,000,000) felons who have been released will remain ineligible to vote in the 2008 Presidential election.13 Speaking of presidential elections and the role that former felons could play, Jeff Manza and Christopher Uggen, authors of the award winning and highly hailed book Locked Out: Felon Disenfranchisement and American Democracy go so far as to say, “The disenfranchisement of former felons in Florida who have completed their entire sentence likely swung that state toward George W. Bush in the 2000 presidential race, effectively deciding both the election and the course of American history.”14 They also argue that the inability of felons to vote in elections from 1974-2000 was crucial in Republican control of the Congress during this period.15

Given that the prison economy has dramatically expanded around the country and that its rate of expansion shows little sign of abating, African American churches will continue to have inside their worship services and the communities they serve, individuals who are disenfranchised from voting. This is an issue ripe for action by church civic and social action committees, African Americans and all organizations concerned with justice and with helping reintegrate former felons into all aspects of community life so that they can be productive citizens.

VI. Books and Other Information on Blacks and Voting Recommended by Terrye Conroy

Many books and articles are now available to provide information on the struggle for voter rights by African Americans. Some are:

- History of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. American Civil Liberties Union presents a Voting Rights Act Timeline online at: Voting Rights Act: Renew. Restore. http://www.votingrights.org/timeline. This comprehensive Voting Rights Act timeline depicts events affecting voting rights from 1776 through August 6, 2007.

- Bass, Jack. Taming the Storm: The Life and Times of Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr., and the South’s Fight over Civil Rights. New York: Doubleday, 1993. In his biography of U.S. District Court and Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr., Bass uses transcripts of testimony and interviews with witnesses, lawyers, law clerks, and the judge himself to convey the events precipitating Johnson’s order allowing the historic march from Selma to Montgomery on March 21, 1965, just months before the passage of the Voting Rights Act.

- Bass, Jack. Unlikely Heroes. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1981. Jack Bass tells the story of the heroic judges of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals (Elbert Tuttle, John Brown, John Minor Wisdom, and Richard Rives) who “helped shape the nation’s Second Reconstruction, and left a permanent imprint on American history” (p.22). Chapter 14, “The Wall Tumbles,” addresses the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the pivotal role of Federal District Court Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr.

- Durham, Michael S. Powerful Days: The Civil Rights Photography of Charles Moore. New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 1991. This book depicts the events of the struggle for civil rights in America through the eyes of photo-journalist Charles Moore as he traveled the South to cover the events of the movement for Lifemagazine. Moore’s photograph collection includes stirring images of the Mississippi voter registration drives as well as the tragedy of Bloody Sunday and the triumph of the Selma to Montgomery march. Samples of Moore’s photographs can be found online at: Kodak’s website, Powerful Days in Black and White. www.kodak.com/US/en/corp/features/moore/mooreIndex.shtml.

- Lawson, Steven F. Black Ballots: Voting Rights in the South, 1944–1969. New York: Columbia University Press, 1976. Reprinted with new preface. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 1999. Page references are to 1999 edition. Lawson underscores how difficult the fight was to “make our nation live up to its democratic ideals” (p.x) by detailing the operations of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, along with those of grassroots organizations, through the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Lawson explains that his somewhat “top down” (p.x) version of history is intended to show that government officials in the United States did not act because it was the right thing to do, but in response to political pressure from African Americans and to overt crises.

VII. Prose Excerpts

Reverend Adam Clayton Powell and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. encouraged their congregations to become active participants in American democracy. Reverend Powell, in a sermon entitled “Democracy and Religion,” told his congregants:

Democracy is by far the best political system under which man lives, but there is no guarantee that it shall continue as such. The only guarantee of a continuation is the improvement of democracy. This can be done only by Christian leadership. Christian leadership is most effective when we go out and preach and teach outside of the church.

There is no inalienable right to govern, but the human spirit does demand to be governed with justice. Politics, like preaching, should be the function of those best fitted to perform its duties. Today, democracy places too much power in the hands of a voting public largely incompetent, and ethically insensitive, which places the unfit in office while others are excluded because of the party system which legislates en masse, and thereby offers too many “pork barrels.”

I call today for the men and women of the church to commit themselves, without reservation, to the democratic ideal but also to a revision of those elements within the democratic system which thwart attainment. The last two of Reverend Powell’s seven mandates for revision are: Sixth, the church should lay upon its members a sense of their responsibility to be a nucleus from which a new democracy is built. And seventh, the church needs to make reason and revelation the approach to the truth. Without reason there is no knowledge of how to act in civic affairs. Without revelation one sees little to ask for.16

On May 17, 1957, Dr. King delivered a sermon entitled, “Give Us the Ballot,” to commemorate the third anniversary celebration of the 1954 Supreme Court Decision. The site was the Lincoln Memorial. In this sermon, (with audience responses bracketed) King’s masterful use of the traditional African American oratorical preaching technique of incremental repetition is shown:

All types of conniving methods are still being used to prevent Negroes from becoming registered voters. The denial of this sacred right is a tragic betrayal of the highest mandates of our democratic tradition. And so our most urgent request to the president of the United States and every member of Congress is to give us the right to vote. [Yes]

Give us the ballot, and we will no longer have to worry the federal government about our basic rights. Give us the ballot [Yes], and we will no longer plead to the federal government for passage of an anti-lynching law; we will by the power of our vote write the law on the statute books of the South [Alright] and bring an end to the dastardly acts of the hooded perpetrators of violence.

Give us the ballot [Give us the ballot], and we will transform the salient misdeeds of bloodthirsty mobs [Yeah] into calculated good deeds of orderly citizens.

Give us the ballot [Give us the ballot], and we will fill our legislative halls with men of goodwill [Alright now] and send to the halls of Congress men who will not sign a “Southern Manifesto” because of their devotion to the manifesto of justice. [Tell ‘em about it.]

Give us the ballot [Yeah], and we will place judges on the benches of the South who will do justly and love mercy [Yeah], and we will place at the head of the southern states governors who will, who have felt not only the tang of the human, but the glow of the Divine.

Give us the ballot [Yes], and we will quietly and nonviolently, without rancor or bitterness, implement the Supreme Court’s decision of May seventeenth, 1954. [That’s right].17

Six years later, Dr. King would return to the Lincoln Memorial and deliver his “I Have a Dream” speech, which included this passage of incremental repetition in which voting is also mentioned:

We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating “for whites only.” [Applause] We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. [Applause] No, no, we are not satisfied and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream. [Applause].18

VIII. Traditional Songs for This Calendar Moment

These three songs embody the courage and dogged determination that Africans Americans have utilized in their quest for full participation in the American electoral process.

Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me ‘Roun’

Ain’t gonna let nobody, turn me ‘roun’

turn me ‘roun’

turn me ‘roun’

Ain’t gonna let nobody, turn me ‘roun’

Keep on walkin’

Keep on walkin’

Walkin’ to the promise land

Ain’t gonna let Bull Connor turn me ‘roun’

turn me ‘roun’

turn me ‘roun’

Ain’t gonna let Bull Connor turn me ‘roun’

Keep on walkin’

Keep on walkin’

Walkin’ to the promise land.19

We Shall Overcome

We shall overcome,

We shall overcome,

We shall overcome, someday.

Oh, deep in my heart, I do believe that

We shall overcome some day.”

We shall live in peace.

We shall live in peace.

We shall live in peace, some day.

Oh, deep in my heart, I do believe that

we shall live in peace, some day.

We shall all be free.

We shall all be free.

We shall all be free, some day

Oh, deep in my heart, I do believe that

We shall all be free some day.20

Lift Every Voice and Sing

Lift every voice and sing

Till earth and heaven ring,

Ring with the harmonies of Liberty;

Let our rejoicing rise

High as the listening skies,

Let it resound loud as the rolling sea.

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us,

Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us,

Facing the rising sun of our new day begun

Let us march on till victory is won.

Stony the road we trod,

Bitter the chastening rod,

Felt in the days when hope unborn had died;

Yet with a steady beat,

Have not our weary feet,

Come to the place for which our fathers sighed?

We have come over a way that with tears has been watered,

We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered,

Out of the gloomy past,

Till now we stand at last

Where the white gleam of our bright star is cast.

God of our weary years,

God of our silent tears,

Thou who has brought us thus far on the way;

Thou who has by Thy might

Led us into the light,

Keep us forever in the path, we pray.

Lest our feet stray from the places, our God, where we met Thee,

Lest our hearts drunk with the wine of the world, we forget Thee;

Shadowed beneath Thy hand,

May we forever stand

True to our God,

True to our native land.21

*Special thanks to Reverend Leroy Elliott of Chicago, Illinois for the use of his version of the song “A Change Is Going to Come.”

Notes

1. Moorer, Lizelia Augusta Jenkins. “The Negro Ballot.” Prejudice Unveiled, and Other Poems. Boston: Roxburgh Pub. Co, 1907. p. 47; Online location: “The Negro Ballot.” Humanities Text Initiative: American Verse Project. 16 May 2001. University of Michigan. http://www.hti.umich.edu/a/amverse accessed 28 June 2008

2. Grant, Joanne. Black Protest: History, Documents, and Analyses, 1619 to the Present. New York: Fawcett World Library, 1968. p. 392

3. Online location: http://www.melanet.com/

4. Ibid.

5. United States. The United States Constitution: What It Says, What It Means: the Text of the United States Constitution, Including an Understandable Description of Each Article and Amendment, Right in the Palm of Your Hand. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

6. Conroy, Terrye. The Voting Rights Act of 1965: A Selected Annotated Bibliography. SC Bar Continuing Legal Education Symposium, October 21, 2005. Online location: http://www.aallnet.org/products/pub_llj_v98n04/2006-39.pdf accessed 28 June 2008

7. The United States Constitution: What it Says, What it Means. Introduction by Caroline Kennedy. Afterword by David Eisenhower. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

8. Online location: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Deal accessed 29 March 2008

9. See Rod Young’s article, “African American Voting Demographics 2008 Democratic Party Statistics.”

10. Morrison, Minion K. C. African Americans and Political Participation: A Reference Handbook. Political participation in America. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2003.

11. The Sentencing Project is a national organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. Since 1986 it has worked to create a fair and effective criminal justice system by promoting reforms in sentencing law and practice, and alternatives to incarceration. For this cultural resource unit see. The Sentencing Project: Research and advocacy for reform. Online location: http://www.sentencingproject.org accessed 29 March 2008

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Manza, Jeff, and Christopher Uggen. Locked Out: Felon Disenfranchisement and American Democracy. Studies in crime and public policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

15. Ibid. Particularly see chapter seven.

16. Powell, Adam Clayton. Keep the Faith, Baby! New York: Trident Press, 1967.

Ward, Jerry Washington. Trouble the water: 250 Years of African-American Poetry. New York, N.Y.: Mentor, 1997. pp. 157-158

17. King, Martin Luther, Clayborne Carson, and Kris Shepard. A Call to Conscience: The Landmark Speeches of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. New York: IPM (Intellectual Properties Management), in association with Warner Books, 2001. pp. 47-48

18. Ibid. p. 84.

19. Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me ‘Roun.’ Negro Spiritual.

20. We Shall Overcome. Negro Spiritual.

21. Lift Every Voice and Sing. By James Weldon Johnson. Considered the Black National anthem.