Cultural Resources

CANCER AWARENESS DAY

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Sunday, October 12, 2008

Yolanda Y. Smith, Guest Cultural Resource Commentator

Assistant Professor of Christian Education, Yale Divinity School

I. Introduction – My Journey with Cancer

My journey with cancer began on Wednesday, March 9, 2005 when I discovered a lump under my right arm. A diagnostic mammogram and ultrasound revealed a mass about the size of a pea deep inside my right breast. The mass was undetectable through the physical exam. However, it showed up clearly on both tests. Although I had had regular mammograms over the years, in that moment, I began to appreciate more fully the value of the mammogram in conjunction with self-examinations. Weeks of doctor’s appointments, exams, tests, and consultations confirmed that I had breast cancer. I would subsequently undergo sixteen weeks of chemotherapy, surgery, and six and a half weeks of radiation.

Prior to my experience with cancer, I had minimal knowledge about the disease, and my knowledge about the impact of cancer on African Americans was even smaller. Like many touched by cancer, the “Big C” conjured up images of chronic illness, lengthy hospital stays, fatigue, discomfort, sickness, and pain. In my mind, cancer was frequently associated with death and despair. After receiving the news that I had cancer, I also began to see myself in this light and wondered whether my life would end early.

Once the initial shock wore off, however, I decided to fight the cancer with every ounce of my being. This meant that I had to rely heavily on the grace of God, my family, friends, colleagues, and the medical professionals attending to my care. As the weeks and months passed by, my support system became a critical part of my journey. I soon discovered how much their love, prayers, encouragement, and acts of kindness bolstered my faith and gave me the courage to fight this disease no matter how difficult or unpleasant. I was particularly inspired by the words of the nurse practitioner, who encouraged me during my initial consultation to live my life as fully and completely as possible during this time. “You are not an invalid,” she said and, from that point on, I refused to think of myself as an invalid or as a person without hope. I was about to engage in the fight of my life, and I was determined more than ever to live! I had embraced the notion that recovery is about choices. We all have the choice, according to Donna Newman, “to be hopeful rather than hopeless,” “to act from faith rather than react from fear,” and “to enjoy life rather than merely survive it.”1

I found meaning in God’s word and in the in the words of other survivors like Audre Lorde, who courageously battled cancer during the late seventies and early eighties. Throughout her journey she maintained, “what is there possibly left for us to be afraid of, after we have dealt face to face with death and not embraced it? Once I accept the existence of dying, as a life process, who can ever have power over me again?”2

I completed my treatment on December 15, 2005, and, while I was cancer free for two and a half years, I am undergoing treatment once again due to a recurrence of the cancer. Despite this new challenge, my doctors and I are optimistic that the cancer will be in remission soon. As I continue my journey toward healing and wholeness, I thank God for the beauty of every day and I take comfort in the prayers of my family, friends, and loved ones.

As a survivor, I am committed to supporting others (especially African American women) with cancer. To this end, I conduct workshops on spirituality and healing, and I make myself available to speak with individuals battling cancer. Although challenging at times, my journey through breast cancer has been a time of profound growth and deepened understanding. Hence, I have gained many life lessons, including the value of faith in times of crises; being grateful for each day; surrounding yourself with people who love and support you; assuming responsibility for your own health care by taking the initiative to ask questions; remembering the importance of monthly self-exams, annual mammograms and early detection; saying thank you; and telling those you hold near and dear how much you love and appreciate them. I am grateful for what this experience has taught me and for every person who has supported me throughout my journey toward healing.3

II. General Statistics

In my quest to take control of my own health care, I began to read about cancer with particular attention to breast cancer in African American women. What I discovered overall, however, was alarming. Most of the literature I read from the American Cancer Society’s “The Complete Guide—Nutrition and Physical Activity” and other sources indicated that African Americans, despite being only about 13% of the total population, have “the highest death rate and shortest survival of any racial and ethnic group in the US for most cancers.”4

These sources also suggest that the reasons for these disparities include multiple complex and interrelated factors such as: poor access to health insurance; low socioeconomic concerns related to income, education, and housing; poor information and access to quality screening and prevention services; genetic factors; certain unhealthy behaviors; environmental issues, cultural barriers, and racial discrimination.5 Consequently, many African Americans are at a great disadvantage when it comes to fighting cancer. I soon realized that because I had access to good quality health care and an early diagnosis of my cancer, I had a very good chance of beating my cancer. This, however, is not always the case for many African Americans. Thus, it is imperative that the African American church and community take an active role in raising awareness about cancer and empowering individuals with knowledge and resources to have the greatest chance of combating cancer successfully.

As of 2003, the combined death rates for all cancers, when compared to white men and women, continued to be 35% higher in African American men and 18% higher in African American women.6 The estimated number of newly diagnosed cancer cases anticipated in 2007 was approximately 152,900. The top three cancers diagnosed in African American men include prostate (37%), lung (15%), and colon/rectum (9%). The top three cancers diagnosed among African American women are breast (27%), lung (13%), and colon/rectum (12%). The estimated number of deaths from cancer among African Americans in 2007 was 62,780.7

The cancers that are responsible for the largest number of deaths among African American men include lung (31%) and prostate (13%), while in African American women, the largest number of deaths from cancer occurs from lung (22%) and breast (19%). The third and fourth most deadly cancers estimated for both African American men and women in 2007 included colon/rectum and pancreas respectively.8 Poor access to quality and timely treatment often results in advanced stage diagnoses for many African Americans. Hence, African Americans are “less likely than whites to survive 5 years after diagnosis for all cancer sites and at all stages of diagnosis.”9

III. Risk Factors

Multiple factors contribute to the risk of cancer in African Americans. For instance, issues related to low socioeconomic status can influence access to quality health care, timely diagnosis and treatment, education and awareness about cancer symptoms, and access to appropriate screening services. As a result, African Americans may be at greater risk of advanced stage diagnosis of cancer resulting in decreased chances for a cure and shorter survival rates.10 Being overweight, obesity, and sedentary lifestyles may increase the risk of developing many forms of cancers. For example, an increased risk of cancers of the breast (among postmenopausal women), colon/rectum, endometrium (uterus), esophagus, and kidney have been linked to being overweight or obese. However, obesity may also raise the risk of additional cancers such as cervical, gallbladder, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, multiple myeloma, ovarian, pancreatic, thyroid, liver, gastric cardia, and aggressive forms of prostate cancer. Although persons being overweight and obese are a growing concern among all communities in the United States, African Americans (especially women and girls) are more likely to be obese or overweight than Caucasians.11 Many studies suggest that incorporating regular exercise and maintaining a healthy body weight can help to lower the risk of some cancers such as breast cancer and colon cancer. However, African Americans are less likely to engage in regular physical activity with women being more sedentary than men.12

Another risk factor for African Americans is smoking and the use of tobacco. In addition to lung cancer, a wide-range of cancers have been linked to smoking including “cancers of the nasopharynx, nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, lip oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, esophagus, pancreas, uterine cervix, kidney, bladder, stomach, and acute myeloid leukemia.” African American men are more likely to contract and die from lung cancer than white men.13

Additional risk factors for African American women relative to breast cancer include age, gender, early onset of menstrual cycle leading to a long menstrual history, hormones, not having children, family history of breast cancer, genetic factors, personal history of breast or ovarian cancer, environmental factors, and early menopause and stress. Although breast cancer in the US occurs more frequently in white women, African American women die from the disease at a higher rate.14 Studies have also shown that African American women are usually “diagnosed at a younger age than their white counterparts, and cancers of similar stage and grade in black women are often faster-growing, more aggressive forms and require more aggressive treatment than those in white women.”15 Consequently, doctors encourage African American women to begin monthly self-breast examinations and request screening services at a younger age. They would further benefit from Founder and CEO of the Sisters Network, Karen Jackson’s assertion that “we must individually and collectively make our health a priority and reject all that stands in the path of reaching that goal.” 16

Finally, African American men have the highest incidence and mortality rates of prostate cancer than other racial/ethnic groups in the US. Compared to white men, African American men are 2.4 times more likely to die from the disease. Significant risk factors for African American men and prostate cancer include possible genetic variations, socioeconomic concerns, insufficient health insurance coverage leading to poor access to health care services, less frequent visits to the doctor for regular physical examinations and screening for prostate cancer, and delayed diagnosis of the disease. Given these trends, health care professionals recommend that African American men receive screening tests for prostate cancer annually beginning at age 45.17

IV. Reducing Risk Factors/Prevention

Some key strategies to reducing cancer include:

1. Avoiding smoking and tobacco use;

2. Maintaining a healthy body weight by eating a balanced diet and increasing regular physical activity;18

3. Taking advantage of high quality screening services and regular follow-ups;19

4. Having regular screening/diagnostic testing as appropriate for various cancers e.g., mammograms for breast cancer, colonoscopy for colon/rectum cancer, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test for prostate cancer, Papanicolaou (Pap) test for cervical cancer, etc;20

5. Consulting a doctor immediately if you are experiencing unusual symptoms. Go to a neighborhood clinic or even an emergency room if you do not have health care, but do see a physician;

6. Working to eliminate racial and ethnic health disparities by raising awareness about socioeconomic concerns, environmental factors, genetic variations, cultural barriers, racial discrimination in health care, and specific health behaviors;

7. Participating in cancer clinical trials;21

8. Mobilizing churches and community organizations to work in partnership with health care providers, public health agencies, and communities of other racial ethnic groups to develop and implement culturally based programs, resources, research opportunities, preventative education, and clinical services;

9. Developing public education campaigns at your church; and,

10. Providing support resources (including psychological and spiritual) for persons affected by cancer and their families.

V. Research and Organizations

Organizations such as the American Cancer Society, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Cancer Institute, and others are involved in numerous research projects to better understand the risk factors, health disparities, environmental factors, genetic variations, early detection and prevention benefits, treatment, survivorship, and other aspects of cancer among African Americans. These organizations also provide information on advocacy, current trends, community networking, clinical trials, health and wellness, education, racial/ethnic disparities in health care, books, pamphlets, resources, and much more. To learn more about these organizations and the services they provide contact their national offices or visit their web sites.22

| Organizations | |

| American Cancer Society National Home Office 1599 Clifton Road Atlanta, GA 30329 1-800-ACS-2345 www.cancer.org | Cancer Care, Inc 275 7th Avenue New York, NY 10001 (212) 712-8400 (admin.) (212) 712-8080 (services) www.cancercare.org |

| Centers for Disease Control |

| Health Resources & Services Administration Hill-Burton Program U.S. Dept. of Health & Human Services Parklawn Building 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 (301) 443-5656 (800) 638-0742 (800) 492-0359 (Maryland area) http://www.hrsa.gov/ | National Cancer Institute Public Information Office Building 31, Room 10A31 31 Center Drive, MSC 2580 Bethesda, MD 20892-2580 (301) 435-3848 (Public Info.) www.nci.nih.gov |

VI. A Meditation for Persons with Cancer

God is Present

God is present with me this day.

God is present with me in the midst of my anxieties. I affirm in my own heart and mind the reality of his presence. He makes immediately available to me the strength of his goodness, the reassurance of his wisdom and the heartiness of his courage. My anxieties are real; they are the result of a wide variety of experiences, some of which I understand, some of which I do not understand. One thing I know concerning my anxieties: they are real to me. Sometimes they seem more real than the presence of God. When this happens, they dominate my mood and possess my thoughts. The presence of God does not always deliver me from anxiety but it always delivers me from anxieties. Little by little, I am beginning to understand that deliverance from anxiety means fundamental growth in spiritual character and awareness. It becomes a quality of being, emerging from deep within, giving to all the dimensions of experience a vast immunity against being anxious. A ground of calm underlies experiences whatever may be the tempestuous character of events. This calm is the manifestation in life of the active, dynamic Presence of God.

God is present with me this day.23

VII. Quotes

“Society has failed the African American woman by devaluing the importance of her health. We must individually and collectively make our health a priority and reject all that stands in the path of reaching that goal.”

--Karen Eubanks Jackson

“Survival means being able to look back and recognize your strengths, weaknesses, challenges, and triumphs, while having the will and character to embrace and look forward to many more. [God] never guaranteed how our gifts would be packaged. . .”

--Arnetta Yarbrough

“The natural healing force within each one of us is the greatest force in getting well.”

--Hippocrates

“Every situation, properly perceived, becomes an opportunity to heal.”

--A Course in Miracles

“Accept what comes to you totally and completely so that you can appreciate it, learn from it, and then let it go.”

--Deepak Chopra

“We bring about new beginnings by deciding to bring about endings. To renew your life you must be willing to change, to make an effort to leave behind the things that comprise your wholeness. The universe rushes to support you whenever you attempt to take a step forward. Any time you seek to be in harmony with life, to make yourself feel more whole, all the blessings that flow from God stream toward you, to bolster you and encourage you, because all life is biased on the side of supporting itself.”

--Susan Taylor

VIII. Songs for this Lectionary Moment

I Want Jesus to Walk with Me

I want Jesus to walk with me

I want Jesus to walk with me

All along my pilgrim journey

Lord, I want Jesus to walk with me

In my trials, Lord, walk with me

In my trials, Lord, walk with me

When my heart is almost breaking

Lord, I want Jesus to walk with me

When I’m in trouble, Lord, walk with me

When I’m in trouble, Lord, walk with me

When my head is bowed in sorrow

Lord, I want Jesus to walk with me. 24

Balm in Gilead

There is a balm in Gilead

To make the wounded whole

There is a balm in Gilead

To heal the sin-sick soul

Sometimes I feel discouraged

And think my work’s in vain

But then the Holy Spirit

Revives my soul again

Don’t ever feel discouraged

For Jesus is your friend

And if you look for knowledge

He’ll ne’er refuse to lend

If you cannot preach like Peter

If you cannot pray like Paul

You can tell the love of Jesus

And say “He died for all.”25

Because He Lives

God sent his Son

They called him Jesus

He came to love, heal, and forgive

He lived and died to buy my pardon.

An empty grave is there to prove

My Savior lives.

How sweet to hold

A newborn baby

And feel the pride, and joy he gives

But greater still the calm assurance

This child can face uncertain days

Because he lives.

And then one day

I’ll cross the river

I’ll fight life’s final war with pain

And then as death gives way to vict’ry

I’ll see the lights of glory

And I’ll know he lives.

Because he lives I can face tomorrow

Because he lives all fear is gone

Because I know he holds the future

and life is worth the living just because he lives.26

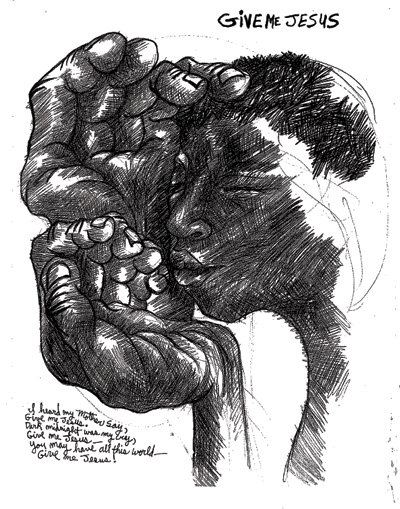

*Artwork by Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson, The Teachings: Drawn from African American Spirituals (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1992). Used by permission of the author.

1. Donna Newman, quoted in The Language of Recovery. Ed. Blue Mountain Arts Collection. Blue Mountain Press, 2000.

2. See Lorde, Audre. The Cancer Journals. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1997. p. 24 Audrey Lorde lost her battle with cancer on November 11, 1992.

3. A shorter version of my journey with cancer will also appear in the 2009 Sisters’ Journey Calendar. Sisters’ Journey is a faith-based support group for African American women (and their family/friends) who have been diagnosed with breast cancer. For more information about the organization, please visit their website at

http://www.yalecancercenter.org/news/2008stories/smart_sisters.html.

4. I found this to be true when I first began researching cancer in 2005, and it continues to be the case even today. See, American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2007-2008. Atlanta, 2007; online location: http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/CAFF2007AAacspdf2007.pdf, accessed 7 May 2008. See also, United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Eliminate Disparities in Cancer Screening & Management.” Office of Minority Health & Health Disparities, 2007; online location: http://www.cdc.gov/omhd/AMH/factsheets/cancer.htm, accessed 7 May 2008; United States. National Institutes of Health. “Disparities: Questions and Answers.” National Cancer Institute, 2007; online location: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/cancer-health-disparities, accessed 7 May 2008.

5. See, American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2007-2008; United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Eliminate Disparities in Cancer Screening & Management;” United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Black or African American Populations.” Office of Minority Health & Health Disparities, 2007; online location: http://www.cdc.gov/omhd/Populations/BAA/BAA.htm, accessed 7 May 2008; and United States. National Institutes of Health. “Disparities: Questions and Answers.”

6. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2007-2008.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid. pp. 4 - 6.

10. Ibid. p.15; United States. National Institutes of Health. “Disparities: Questions and Answers;” United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Black or African American Populations,” 2008. p. 2; National Cancer Institute. “Cancer Health Disparities: Questions and Answers.”

11. American Cancer Society. “The Complete Guide—Nutrition and Physical Activity.” Nutrition and Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Atlanta: 2006. Online location: http://www.cancer.org/docroot/PED/content/PED_3_2X_Diet_and_Activity_ Factors_That_Affect_Risks.asp, accessed 7 May 2008; American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2007-2008. p. 17.

12. American Cancer Society. “The Complete Guide—Nutrition and Physical Activity;” and, American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2007-2008. pp. 17-19.

13. One reason for this disparity, according to the research, is that African American men “often smoke cigarettes more intensively and are more likely to smoke mentholated brands, which have been shown to have higher carbon monoxide concentrations than non-mentholated cigarettes and may be associated with a greater absorption of nicotine.” See, American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2007-2008. pp. 15-16.

14. Brown, Zora K., LaSalle D. Leffall and Elizabeth Platt. 100 Questions & Answers about Breast Cancer. Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers, 2003. pp. 17-30; National Cancer Institute. “Cancer Health Disparities: Questions and Answers.” p. 3. For additional information on warning signs, recommended steps for early detection, factors that place women at increased risk for breast cancer, and methods for detecting breast cancer early see, Kelly, Pat, and Mark N. Levine. Breast Cancer: The Facts You Need to Know About Diagnosis, Treatment, and Beyond. Buffalo, NY: Firefly Books, 2003. For specific information on African American women see, The Sisters Network website http://www.sistersnetworkinc.org/cancer-education.asp.

15. Brown, Zora K., LaSalle D. Leffall and Elizabeth Platt. 100 Questions & Answers about Breast Cancer. p. 23. See also, American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2007-2008. p. 8.

16. Karen Eubanks Jackson organized the Sisters Network, Inc., a National African American Breast Cancer Survivorship Organization, in 1994. Quoted in Thoughts of Survivors: A Journal for Inspiration and Empowerment for African American Breast Cancer Survivors. Houston: Sisters Network, Inc. p. 9.

17. National Cancer Institute. “Cancer Health Disparities: Questions and Answers.” p. 7. Online location: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/cancer-health-disparities; American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2007-2008. pp.12 - 13, 21.

18. The American Cancer Society recommends that adults engage in at least “30 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity, above usual activities, on 5 or more days of the week; 45 to 60 minutes of intentional physical activity are preferable.” Children and adolescents should engage in “at least 60 minutes per day of moderate to vigorous physical activity at least 5 days per week.” See, American Cancer Society. “The Complete Guide—Nutrition and Physical Activity.” Nutrition and Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee; and, American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2007-2008. p. 17.

19. Screening tests are an important resource because they can help detect some cancers at an early stage. Early detection tests for some cancers “can lead to the prevention of cancer through the identification and removal of precancerous lesions. Screening can also greatly improve the chances of cure, extend life, reduce the extent of treatment needed, and thereby improve quality of life for cancer survivors.” See, American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2007-2008. p. 19.

20. For additional information on screening/diagnostic testing see, “Screening Guidelines for the Early Detection of Cancer in Asymptomatic People.” American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2007-2008. p. 20; and, United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Eliminate Disparities in Cancer Screening & Management.”

21. For more information on clinical trials see, http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials.

22. See also, National Institute of Cancer. Continuing Umbrella of Research Experiences (CURE). “Opportunities for Career and Training Development for Minority Trainees.” Comprehensive Minority Biomedical Branch. Online location: http://minorityopportunities.nci.nih.gov/mTraining/index.html; United States. National Institutes of Health. “Body and Soul: A Celebration of Healthy Eating & Living.” Online location: http://www.bodyandsoul.nih.gov; and, Dept. of Health & Human Services. Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH 2010). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1 May 2008. Online location: www.cdc.gov/reach2010.

23. Thurman, Howard. God is Present from the book Meditations of the Heart. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1999, p.50.

24. I Want Jesus to Walk With Me. African American Heritage Hymnal. Chicago IL: GIA Publications, 2001. #563

25. There is a Balm in Gilead. African American Heritage Hymnal. #524

26. Gaither, Gloria. Because He Lives. Old Tappan, N.J.: F.H. Revell Co., 1977.