Cultural Resources

REVIVAL II

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Sunday, August 24, 2008

William H. Wiggins, Jr., Lectionary Team Cultural Resource Commentator

I. Historical Background

(A) In the first three verses of the biblical text for this cultural moment, Elisha says, “Hear the word of the Lord: thus says the Lord, ‘Tomorrow about this time a measure of choice meal shall be sold for a shekel, and two measures of barley for a shekel, at the gate of Samaria.’ Then the captain on whose hand the king leaned said to the man of God, ‘Even if the Lord were to make windows in the sky, could such a thing happen?’ But he said, ‘You shall see it with your own eyes, but you shall not eat from it’” (2 Kings 7:1-3). In sum, Elisha, the prophet, is prophesying a future manifestation of the Word of God to a disbelieving audience. Prophetic African American preachers have historically used revivals and camp meetings to do the same—prophesy messages about future manifestations of God, often to unbelievers. Yes! These preachers had unbelievers among their own congregations, because it was hard for many to believe that slavery, segregation, and the brutality that accompanied these systems could be over-turned. Even today, the prophet/preacher is up against those who find it difficult to imagine that God can turn around blighted neighborhoods, crime-ridden communities, and lost young people with a mind for violence. But he or she who speaks for God must always be courageous enough to speak of the future manifestations of God, even when few believe due to harsh and what appear to be hopeless circumstances. Revivals provide platforms for just such brave articulations of the future manifestations of God, and for articulation of doom for those who do not heed the ways of God.

The religious fervor of American revivals and camp meetings spawned and nurtured the Abolitionist movement. Distinguished American historian John Hope Franklin noted that, “In the West, it [the Abolitionist movement] was connected with the Great Revival (The Second Great Awakening), of which Charles G. Finney was the dominant figure, emphasizing the importance of being useful and thus releasing a powerful impulse toward social reform. The young converts joined Finney’s Holy Band, and if the abolition of slavery was a way of serving God, they were anxious to enter into the movement wholeheartedly.”2 Although Finney should not be labeled an ardent abolitionist, he did use revivals as opportunities to address slavery as a sin when it was expedient to do so.

(B) Most often, black revivalists received very limited support of their efforts to strike a blow against slavery as they offered revival messages. Famous white revivalist Dwight Moody, who preached to millions of whites, segregated his revivals from 1876 through the 1890s, agreeing only to preach to blacks in separate services. Abolitionists Frederick Douglass and Ida B. Wells condemned him for condoning racism from the pulpit and using revivals to do so. They even “claimed that Moody and his ministerial colleagues,” which included Phillip Brooks, Henry Ward Beecher, and Frances Willard among others, were fanning racism through not aggressively condemning slavery. “Of all the forms of Negro hate in this world, save me from that one which clothes itself with the name of the loving Jesus.”2 Ida B. Wells said of Moody’s revivals: “I remember very clearly that when Rev. Moody had come to the South with his revival sermons, the notices printed said that the Negroes who wished to attend . . . would have to go into the gallery or, that a special service would be set aside for colored people only . . . Mr. Moody has encouraged the drawing of the color line in churches by consenting to preach on separate days, and in separate churches to colored people.”3

So, while black revivalists where trying to teach their people that God did not create them to be slaves, they were contending with racism by some of the most well-known white revivalists in the country.

II. A Revival Sermon that Became the Talk of the Nation

In 2001, Reverend Dr. Jeremiah Wright Jr., then the pastor of Trinity United Church of Christ of Chicago, began delivering, during revivals, a prophetic rebuke of what he saw as failures of the American government.

Wright said in part, “[T]he United States of America government, when it came to treating her citizens of Indian descent fairly, she failed. She put them on reservations. When it came to treating her citizens of Japanese descent fairly, she failed. She put them in prison camps. When it came to treating her citizens of African descent fairly, America failed. She put them in chains. The government put them in slave quarters, put them on auction blocks, put them in cotton fields, put them in inferior schools, put them in substandard housing, put them in scientific experiments, put them in the lowest paying jobs, put them outside the equal protection of the law, kept them out of the racist bastions of higher education and locked them into the position of hopelessness and helplessness.”4

A part of what made this message explosive is that it was delivered after the bombings of the World Trade Centers and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001. However, even with that, most Americans would never have paid attention to the sermon had it not been for the fact that the now retired Reverend Wright was the pastor to Barack Obama, the first African American with a realistic chance of becoming president of the United States, and Wright had also delivered this message at Trinity United Church of Christ. The sermon was obtained by media and used to paint Wright as unpatriotic and an angry black man, and to suggest that as a member of his church for 20 years, Obama shared Wright’s sentiments. More of the message can be heard on the following video.

III. Contemporary Revivals

The four-generational revival cycle, which is long known to whites in America, now appears to have become a permanent aspect of many African American churches and families. Now, “[t]he first generation gets converted; the second generation gets educated; the third gets rich; and the fourth goes to hell!”5 If the four-generational revival cycle is true, it may be one reason why revival attendance and the length of revivals in churches in historic African American denominations have lessened. Gone are the days of seven day, and even five day, revivals. Also gone are mourner’s benches (where persons were to sit until they could publicly confess that they had experienced spiritual transformation). Many churches in historically black denominations have even done away with devotional services that open revivals and testimonies by persons attending revivals. In many urban centers, the devotional services and testimony services have been replaced by what is called Praise and Worship.

So, what can one expect in a revival service in a historically black church today? You will find mixture of older worship practices, and worship practices that have become pervasive in the last twenty years. Particularly since 2000, revival services are filled with upbeat singing and ecstatic praise by attendees. Historically, this type of worship atmosphere was found primarily in Holiness-Pentecostal churches. However, currently, even in churches once known for quiet, contemplative worship, exuberant worship can now be heard during revivals. Further, in larger churches, although choir singing remains a staple, what are called Psalmists (guest singers and musicians) can often be heard. Given that frequently these singers and musicians are relatively well-known artists, it is clearly understood that attendees now come to revivals to hear these singers and musicians as much as, and sometimes more than, they come to hear revival preachers.

The messages in these services tend to rarely be prophetic; they offer listeners positive outcomes in life, and they have spawned new black church phraseology, such as: “It’s your season,” “Expect your breakthrough,” and “You are the head and not the tail.” They have also introduced rhetorical devices that have led to the historical black church call-and-response now mainly being led by the preacher and not the congregation. The most common rhetorical devices include: asking congregants to turn to other congregants and repeat a phrase to them, asking congregants to high-five another congregant, asking congregants to engage in 60 seconds of praise or other action, and asking congregants to repeat after the preacher.6

IV. Poetry and Prose Excerpts

Images of southern revivals and camp meetings are recurrent scenes in African American literature. For example, James Baldwin’s novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, features the revival at which Gabriel Grimes, the tormented stepfather of John Grimes, the novel’s protagonist, delivers his first sermon. And Maya Angelou shares her childhood memories of the camp meetings she attended while growing up in Stamps, Arkansas with readers of her autobiography, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. First, she recalls the setting: “The cloth tent had been set on the flatlands in the middle of a field near the railroad tracks. The earth was carpeted with a silky layer of dried grass and cotton stalks. Collapsible chairs were poked into the still-soft ground and a large wooden cross was hung from the center beam at the rear of the tent. Electric lights had been strung from behind the pulpit to the entrance flap and continued outside on poles made of rough two-by-fours.”7 Next, she describes the ecumenical nature of the congregation: “Everyone attended the revival meetings. Members of the hoity-toity Mount Zion Baptist Church mingled with the intellectual members of the African Methodist Episcopal and African Methodist Episcopal Zion, and the plain working people of the Christian Methodist Episcopal. These gatherings provided the one time in the year when all of those good village people associated with the followers of the Church of God in Christ.”8

V. Traditional Songs

“Something Happened When He Saved Me,” an old camp meeting conversion song, and “I Saw the Light,” written in 1948, are both revival favorites. The first appears to only concern spiritual conversion, but was also sung by those who had gained a taste for freedom. Something had indeed happened to them. “I Saw the Light” was also a song that meant more than could be seen at first glance. There was the light that was brought by spiritual conversion, and there was the light that shined when one realized that they were a citizen due equal treatment and equal rights as all other citizens.

Something Happened When He Saved Me

Something happened when he saved me,

It happened in my heart,

It made my soul rejoice;

Something happened when he saved me,

Something happened in my heart.

It was Monday when he saved me,

It happened in my heart,

It made my soul rejoice;

Something happened when he saved me.

Something happened in my heart.

It was Tuesday when he saved me,

It happened in my heart,

It made my soul rejoice;

Something happened when he saved me,

Something happened in my heart.

It was Wednesday when he saved me.

It happened…

It was Thursday…

It was Friday…

It was Saturday…

It was Sunday…9

I Saw the Light

I wandered so aimless my heart filled with sin

I wouldn't let my dear Savior in

Then Jesus came like a stranger in the night

Praise the Lord I saw the light

I saw the light I saw the light

No more darkness no more night

Now I'm so happy no sorrow in sight

Praise the Lord I saw the light

Just like a blind man I wandered alone

Worries and fears I claimed for my own

Then like the blind man that God gave back his sight

Praise the Lord I saw the light

Chorus

I was a fool to wander and astray

Straight is the gate and narrow the way

Now I have traded the wrong for the right

Praise the lord I saw the light.10

The Negro Spiritual “There’s a Meeting Here Tonight,” which was composed by black and unknown bards who had attended a community camp meeting, gives its listeners a glimpse of the denominational loyalties of the worshippers.

There’s a Meeting Here Tonight

There’s a meeting here tonight. (Repeat)

I can tell by your very walk, there’s a meeting here tonight.

My mother says it is the best.

There’s a meeting here tonight.

To live and die a Methodist!

There’s a meeting here tonight.

I’m Baptist bred and Baptist born,

There’s a meeting here tonight.

And when I’m dead, it’ll be a Baptist gone!

There’s a meeting here tonight.11

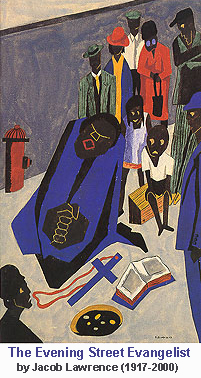

Possible Program Illustration:

Jacob Lawrence’s painting, “The Street Evangelist” which we are honored to feature as our web image for this moment on the calendar

Notes

-

Franklin, John Hope. From Slavery to Freedom: A History of Negro America. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1969. pp. 244-245

- Blum, Edward J., and W. Scott Poole. Vale of Tears: New Essays on Religion and Reconstruction. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2005. p. 101

- Ibid

- To see the sermon out of which these words emanated, see Jeremiah Wright’s “The Day of Jerusalem’s Fall.” In 9.11.01: African American

Leaders Respond to an American Tragedy. Simmons, Martha J., and Frank Thomas, eds. Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press, 2001. pp 81-91

- Jewett, Robert. Mission and Menace: Four Centuries of American Religious Zeal. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. p. 66

- For more information on modern rhetorical devices by black preachers see the article, “I Wish I had Somebody:

The Rhetorical Devices of Black Preaching.” Blow, David L. Sr., and Frank A Thomas, The African American Pulpit (Fall 2002).

- Angelou, Maya. I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. New York: Random House, 1969. p. 118

- Ibid. p. 120

- Something Happened When He Saved Me. Traditional

- I Saw the Light. Hank Williams, Jr., 1947

- There’s a Meeting Here Tonight. Negro Spiritual