Cultural Resources

“WHO SO EVER WILL” SUNDAY

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Sunday, August 28, 2011

(Please visit the archive section of the Lectionary Dialogue Corner for articles on this topic. Scroll to the bottom of the Dialogue Corner page.)

Bernice Johnson Reagon, Lectionary Team Cultural Resource Commentator

I. Introduction

Hospitality is presented to us in the Bible as not just a practice for Christians but as an ethical way of living that is required. Hospitality confirms the high worth and common humanity of all people! On this Sunday we want to encourage churches to begin a dialogue that welcomes Gay, Lesbian, Bi-Sexual, Transgender, and those who self-identify as Queer. For many black persons, those in these groups are identified by the Church as strangers, even if they have longed served in the Church. The first level of getting to know anyone is the extension of hospitality, not judgment or hostility.

II. Etymology

Hospitality: late 14c., “act of being hospitable,” from O.Fr. hospitalité, from L. hospitalitem (gen. hospitalitas) “friendliness to guests,” from hospes (gen. hospitis) “guest” (see host )

Host: “person who receives guests,” late 13c., from O.Fr. hoste “guest, host” (12c.), from L. hospitem (nom. hospes) “guest, host,” lit. “lord of strangers,” from PIE ghostis- “stranger” (cf. O.C.S. gosti “guest, friend,” gospodi “lord, master”; see guest

Guest: O.E. gæst, giest (Anglian gest) “guest; enemy; stranger,” the common notion being “stranger,” from P.Gmc. gastiz (cf. O.Fris. jest, Du. gast, Ger. Gast, Goth. gasts “guest,” originally “stranger”), from PIE base ghosti- “strange” (cf. L. hostis “enemy,” hospes “host”—from hosti-potis “host, guest,” originally “lord of strangers”—Gk. xenos “guest, host, stranger”; O.C.S. gosti “guest, friend,” gospodi “lord, master”). Spelling evolution influenced by O.N. cognate gestr (the usual sound changes from the O.E. word would have yielded Mod.Eng. yest). Phrase be my guest in the sense of “go right ahead” first recorded 1955.

Strange: late 13c., “from elsewhere, foreign, unknown, unfamiliar,” from O.Fr. estrange (Fr. étrange) “foreign, alien,” from L. extraneus “foreign, external,” from extra “outside of” (see extra). Sense of “queer, surprising” is attested from late 14c. Stranger, attested from late 14c., never picked up the secondary sense of the adjective. As a form of address to an unknown person, it is recorded from 1817, Amer.Eng. rural colloq. Meaning “one who has stopped visiting” is recorded from 1520s.1

III. Not Welcomed

Stranger Blues

I’m a stranger, stranger here

I’m a stranger everywhere

Lord I would go home

But I’m a stranger there

I’d rather drink muddy water

I’d rather sleep on a hollow log

Than to stay in this city

Being treated like a dirty dog

I got up this morning

I put on my walking shoes

I’m going down to the road

Cause I got that walking blues

I’m a stranger here, stranger here

I’m just passing through your town

You know I would stay,

But you people keep dogging me round.2

The text of the secular “Stranger Blues” provides an inside look from one who provides an extended and varied view of what it is like for one to find that there is no place where one is ‘at home,’ welcome to enter and be a part of the family, the group, the town, the congregation. Our rationale statement for this unit calls us as Christians to be hospitable to strangers. It supports the idea of inside/outside, or ‘those who stand at the door and knock.’ This unit also calls us to look at those members of our community who were ‘born and raised in the Church’ for whom the Church is a guiding force of their lives. These brothers and sisters are baptized, are members, serve on the usher boards and various committees, sing and direct for the choirs, play the instruments for the services, and contribute funds to support the life and service of the Church, all of without which the congregation would be greatly diminished.

III. Personal Experience

I was in church one Sunday morning and could not get in my usual seat, as it was reserved for a family gathered for a ceremony to have a baby dedicated. The family took up two rows, mostly women. When the service opened to the dedication, they all stood with a commitment to this new life. This welcoming was different than the Baptist churches I grew up in. Where I grew up, in a church family in Southwest Georgia, when a girl became pregnant out of wedlock, she was ‘put out’ of the church. The entire time she was pregnant she was out of the church. She had to come back to the church and apologize to get back in. The male partner, often known, remained unnamed and within the circle. It always made me angry to see the church put a young woman out of the church just when she needed a supportive and protective community. I thought about the lesson of Mary, a young unmarried pregnant woman, who was chosen to be the mother of one who would be Savior. It was a very special experience that morning to find a church that really had doors wide enough to receive all who sought entry—a teenage mother with a new baby, embraced by her large supporting family inviting all to come in. This is a story about welcoming those who are in need of a spiritual supporting community; being inside the Church community is what we are called to as Christians.

In our culture, gender identity is formed with a preferred ‘normal’ coming not at the center but at the extremes of the gender spectrum. As some of our children move through early adolescence, in some cases, their gender development evolves nearer the center of the gender spectrum rather than the outer edges—where male and female is expressed as opposites. These children become ‘known’ as ‘not normal,’ and though not put out of their church, they receive a strong message to ‘curb the expression of themselves and their nature.’ These young people grow up in an environment that radiates to them that they are “wrong,” a “violation,” “unhealthy.” Some leave their worship community. Many stay, weathering a storm that surrounds them with energy and many times spoken words from the pulpit that make it extremely challenging for them to walk with their heads high as children of a loving God. We all know that the Black church has always had within its midst those whose gender identities and sexual attractions do not operate at the extreme ends of the gender male and female spectrum. Then there are those within all human cultures that come into an awareness of belonging much more toward the center where gender pulls—from both or opposite their male and female sides; for them, this is their ‘normal.’

IV. Gender Development and Family and Community Awareness

Representing a more nuanced, and ultimately truly authentic model of human gender, “Gender Spectrum” is an information site providing concepts about gender and especially the impact on a strong culture that has little room for accepting variations that occur throughout living forms:

Just as I Am

Just am I am without one plea

But that Thy blood was shed for me,

And that thou bidst me come to Thee,

O Lamb of God, I come! I come!

3. Just as I am though tossed about

With many a conflict, many a doubt,

Fightings and fears within, without,

O Lamb of God, I come! I come!4

More recently, our children have begun to demand respect for who we/they are and the right to not be of that which is ‘despised.’ And even more recently, a few leaders of the Black church family have begun to engage in a dialogue about what is an ugly damaging history. In different ways the Black Church has begun to ask: Can we continue to do this? Will we begin to reach inside and outside of ourselves and find ways to go forward without being a damaging, destructive presence to our own children?

Keith Boykin wrote an article about an African American church that dismissed its own son:

The Rev Benjamin Reynolds

(It’s Me It’s Me Oh Lord), Standing in the Need of Prayer

It’s me, it’s me, it’s me oh Lord, standing in the need of prayer

Not my sister nor my brother but it’s me oh Lord, standing in the need of prayer

Not my mother or my father but it’s me…

Not the deacon, nor the preacher but it’s me…6

V. Black Church Leaders Ask for Forgiveness from the LGBT Community: In an unusual meeting, several ministers apologize to gays about how they have been treated.

By Delano Squires

A rather unusual event recently took place in the Washington, D.C., suburb of Fort Washington, Maryland. Several ministers of black churches met with members of the LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender) community—and formally apologized for what the organizers described as the Church’s judgmental attitude toward individuals who experience same-sex attraction and their loved ones.

Although a sincere apology is often the first step to restoring a fractured relationship, our culture has made public apologies into a performance art, characterized by carefully scripted PR creations and only token acknowledgments of actually having done wrong.

It was with this skepticism that I attended the forum at Carolina Missionary Baptist Church on Feb. 19, billed as an opportunity for people to express their thoughts and feelings in a safe environment. Anthony E. Moore, pastor of Carolina, moderated the dialogue and stated up front that the forum was not intended to be one in which the Church took a theological position on homosexuality. My pastor, Keith Battle, attended on behalf of Zion Church, and other sponsoring churches included Pilgrim Baptist Church in D.C. and New Vision Church in Bowie, Maryland.

When I arrived, someone was recounting what it has been like to be born a man while feeling, and ultimately living, like a woman. The speaker explained that she turned to prostitution and drugs after experiencing rejection from members of her family and church. She said that eventually she came back to church, committed her life to Christ and started to translate her pain into purpose.

There were similar stories throughout the two-hour forum, all with one common theme: The church, the one place that should represent the epitome of love, was often the most uncaring and unsafe place for these individuals when they were at their most vulnerable. Bishop Kwabena Rainey Cheeks, the openly gay pastor of Inner Light Ministries, a nondenominational church in Washington, bluntly declared that “the most dangerous place for a gay and lesbian person is the black church.”

Moore listened intently as people shared their experiences, often taking notes while they spoke. Toward the end of the event, he reinforced the sincerity of the church’s apology by pledging to continue the dialogue and to make concerted efforts to make his ministry more inclusive of members of the LGBT community.

. . .

Although the image of a preacher declaring eternal damnation resonates with many members of the LBGT community, not all churches have taken this position. A recent New York Times article cited U.S. Census Bureau data indicating that child rearing among same-sex couples is more common in the South than in any other part of the country, and found eight churches in Jacksonville, Fla., that openly welcome gay worshippers. It remains to be seen, however, to what extent the recent forum and the demographic trends in historically conservative regions foreshadow a broader shift in black churches’ attitudes toward gays and lesbians .7

VI. Poison Pews: African-American leaders talk about homophobia in the black church

by Yusef Najafi

African-American leaders, students and activists gathered for nearly two hours inside Howard University’s Howard Thurman Chapel in Northeast D.C. recently to discuss homophobia in African-American churches. Among those gathered, it was generally agreed that not only does such homophobia exist, but most would rather ignore it.

“We have people who are victimized every day in the church,” said Dustin Baker, a gay student at the Howard University School of Divinity, as he welcomed the crowd to the forum on Thursday afternoon, March 26. “It’s a hard statement to say, but the reality is oppressed people do oppress people. At one point in time, the black church was an oppressed group of people...and at times we oppress individuals, especially people of same-gender-loving communities.” Baker set an emotional tone as he shared with the audience of about 60 people that during his work as a counselor for gay youth, two—one 14, the other 17—committed suicide. The Howard University School of Divinity’s Student Government Association (SGA) and the People for the American Way Foundation organized “Homophobia in the Black Church” as part of the historically black college’s celebration of Harambee 2009. Joi R. Orr, president of the SGA, described Harambee as “the Kenyan tradition of community empowerment.” |

Donna Payne |

Sharon J. Lettman, executive vice president for leadership programs and external affairs for the People for the American Way Foundation, the organization that sponsored the discussion, commended Baker’s work before explaining why the discussion was crucial.

“Amongst the African-American community, sexuality is not a conversation,” Lettman said. “It’s not just homosexuality—sexuality is not a conversation.

“Gay rights is not a white-male issue,” she added, pointing to the need for a greater African-American counter to homophobia. “We have allowed a subculture to be created within our community because we won’t have this conversation.”

To help initiate a national discussion about homophobia in the black church, Lettman said a transcript of the forum would be distributed across the country in the near future.

Panelists for the discussion were Rev. Dr. Kenneth Samuel, senior pastor of Victory for the World in Stone Mountain, GA; Donna Payne, associate director of diversity at the Human Rights Campaign; Rev. Osagyefo Uhuru Sekou, Fellow In Residence at the Brooklyn Society for Ethical Culture; Rev. Byron Williams, pastor of the Resurrection Community Church in Oakland, CA.; and Rev. Dr. Ronald Hopson, an ordained minister, psychologist, and professor at Howard University’s Department of Psychology and School of Divinity.

Rev. Tony Lee initiated the panel discussion, which frequently touched on biblical scripture regarding homosexuality.

Samuel explained that biblical interpretation is a “very dangerous thing.”

“Certain text in the Bible, as we know, had been used to support slavery in America for over 200 years,” he said. “Certain texts have been used to justify patriarchy and sexism, militaristic warfare, beating of children.... We have toxic text in the Bible that needs to be interpreted in the light of the truth, and...from the light and lenses of the all-inclusive love of Jesus.”

Samuel said that before the Civil Rights Movement, African Americans had to find a way to believe in what was “good and godly,” while reinterpreting text in the Bible that denied basic humanity.

“I think we’re at that crossroads again.” he said. “Certainly in regards to LGBT persons, I think we have to look at that text through interpretative lenses and not literalistic lenses, because those literal lenses are very deadly, very dangerous.”

. . .

[Donna] Payne made the conversation more personal, offering a crossroads she traveled with her mother. She spoke of a conversation in which she advised her mother that her work at the Human Rights Campaign would likely lead to her appearing on television, identifying her to TV audiences far and wide as an African-American lesbian.

“She said, ‘Oh my goodness, look, I love you, but do you have to tell everybody?’” Payne remembered. “That is what every LGBT African American faces. The first frontier is within the church, their family.”

Payne said a recent study conducted among 5,000 GLBT people of color found that respondents identified their standing within their religious communities as something of great importance. They do not want to leave those communities, Payne explained, but homophobia is driving them away. The respondents’ concerns about their families and society as a whole were secondary.

In talking about solutions regarding homophobia in the black church, the panelists were all in agreement that it’s a conversation that must continue beyond the Thursday forum.

“Open, candid, honest dialogue is the first step in dismantling prejudice of any kind,” Samuel said.

Regarding more specific solutions, such as educating children, Payne suggested churches work with the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice.

Payne also urged that ministers who support GLBT people should contact the HRC or the National Black Justice Coalition, of which she is a board member, to “create a vehicle” that would educate the country on issues ranging from homophobia to distinct issues the transgender community faces.

“If LGBT people keep coming to funerals where you take a transgender [woman] and put [her] into a suit or something that’s totally against who they were, that is so painful and hurtful to the community. It’s something that everybody must be sensitive around, and it’s something that happens particularly in the African-American community. I’ve seen it over and over again.”8

VII. The Black Closet: The Need for LGBT Resources and Research Centers on Historically Black Campuses

by Victoria Diane Kirby

At the same time Howard University hosts a dialogue on Homosexuality and the Black Church, in her article, “The Black Closet; the Need for LGBT Resources and Research Centers on Historically Black Campuses,” Victoria Diane Kirby writes of the intertwined history of the Black church with education and that of America’s HBCUs.

The initial goal of HBCUs was to educate teachers and preachers for newly freed slaves. As a result, churches and missionaries created denominational schools and colleges across the South. Those religious ties continue to be a deep influence on the institutions today. Many members of the clergy believe that the Bible allows heterosexism and homophobia. This belief is supported by the six scriptures in the Bible that reference homosexuality (Genesis 1-2, 19:1-9; Leviticus 18:22, 20:13; 1 Corinthians 6:9; Romans 1:26-27; and 1 Timothy 1:10). As such, the self-worth and self-esteem of homosexual congregants and their partners are diminished by the attitudes that exist within the leaders and fellow congregants of the church (Miller 2000). Same gender loving (SGL) members of the congregation listen to sermons from the pulpit that say that they are going to Hell if they do not change their “lifestyle.” This doctrine and environment play a major role in the resistance toward the creation of not only resource centers, but also LGBT student groups and antidiscrimination policies that offer protection for sexual orientation and gender expression.

The Black church’s influence on the Black community has impacted LGBT students at HBCU campuses in a variety of ways. Many students have internalized the biblical concept of “being” an abomination and have simply accepted the fact that they are going to Hell (Kirby 2009). Having a negative self-concept plays a major role in youth suicides, in how well one does in school, and in how one interacts with society at large.9

VIII. Understanding the Radical Inclusiveness of Jesus

by Bishop Kwabena Rainey Cheeks

|

|

People often ask me what we at Inner Light Ministries [the church where Cheeks is pastor] mean by “the radical inclusiveness of Jesus Christ.” We believe that “radical inclusiveness” is to affirm God’s unconditional acceptance and universal law of love. This mandates that we have love for God, ourselves and our neighbors. …The “theology of Jesus” is inclusive, but the “theology about Jesus” is generally selective. The first accepts everyone as part of the body of Christ. The second requires that one have certain qualifications and meets certain standards.

We believe the answer lies in the life of Jesus and see him as a radical person. Jesus the Christ did not differentiate, nor did he segregate. He accepted everyone as the same. He had women and children around him, he healed people on the Sabbath and touched everyone, from the “haves” to the “have nots” and all those between.

So, I go back to the first question: Who do we not permit to sit at the table of God? Look at the congregations in the churches you are familiar with. Does it match the community? Does it ordain women who so diligently serve in that church? Or, are they only able to serve the food, but not sit at the table? What about gays, lesbians and bisexuals? Is it all right for them to sing in the choir, play the piano, serve on committees and financially support the church, as long as they do not announce themselves—but not sit at the table? Should I even mention the word transgender? Do they even get invited into the room?

Right now, the Episcopal Church is struggling with the idea of having a known gay Pastor become a Bishop. Why now is it suddenly so troubling for him to hold the office of Bishop? He can enter the room, but maybe not sit at the head of the table? What about people with a different spiritual practice, can they visit? Or what about single parents or even a person living with HIV/AIDS? Are they allowed to sit at the table of Christ?

The scripture says, “Who so ever will, let them come.” It does not say, who so ever will, let them come, “if….” Inner Light Ministries not only asks the question: “What would Jesus do?” We work at doing what Jesus did. Therefore, the theology of Christ is not difficult to understand. It simply charges us to love God, ourselves and our neighbors. That, for some people, is radically inclusive.10

I’m Gonna Eat at the Welcome Table

I’m gonna eat at the welcome table, (oh yes)

I’m going to eat at the welcome table, some of these days, hallelujah

I’m gonna eat at the welcome table

I’m gonna eat at the welcome table some of these days

I’m gonna walk the streets of glory,.(Greenville, Selma, Albany..)

I’m goin’ down to the river of Jordan,...

God’s gonna set this world on fire,...

I’m gonna tell God how you treated me,...11

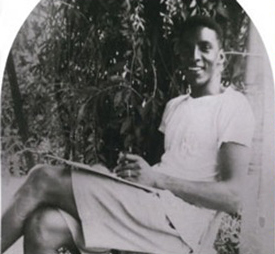

IX. Bayard Rusting: Pacifist, Activist, Major Strategist

In February 1956, when Bayard Rustin arrived in Montgomery to assist with the nascent bus boycott, Martin Luther King, Jr. had not personally embraced nonviolence. In fact, there were guns inside King’s house, and armed guards posted at his doors. Rustin persuaded boycott leaders to adopt complete nonviolence, teaching them Gandhian nonviolent direct protest.

Apart from his career as an activist, Rustin the man was also fun-loving, mischievous, artistic, gifted with a fine singing voice, and known as an art collector who sometimes found museum-quality pieces in New York City trash. Historian John D’Emilio calls Rustin the “lost prophet” of the civil rights movement.12

Rustin’s biography is particularly important for lesbian and gay Americans and all Americans, highlighting the major contributions of a gay man to ending official segregation in America. Rustin stands at the confluence of the great struggles for civil, legal and human rights by African-Americans and lesbian and gay Americans. In a nation still torn by racial hatred and violence, bigotry against homosexuals, and extraordinary divides between rich and poor, his eloquent voice is needed today.

In a nation still torn by racial hatred and violence, bigotry against homosexuals, and extraordinary divides between rich and poor, his eloquent voice is needed today.

A master strategist and tireless activist, Bayard Rustin is best remembered as the organizer of the 1963 March on Washington, one of the largest nonviolent protests ever held in the United States. He brought Gandhi’s protest techniques to the American Civil Rights movement, and was with Ella Jo Baker, a major strategist in sustaining the infrastructure for the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Despite these achievements, Rustin was silenced, threatened, arrested, beaten, imprisoned, and fired from important leadership positions, largely because he was an openly gay man in a fiercely homophobic era. Five years in the making and the winner of numerous awards, Brother Outsider presents a feature-length documentary portrait, focusing on Rustin’s activism for peace, racial equality, economic justice, and human rights.

Today, the United States is still struggling with many of the issues Bayard Rustin sought to change during his long, illustrious career. His focus on civil and economic rights and his belief in peace, human rights, and the dignity of all people remain as relevant today as they were in the 1950s and 60s.

Bayard Rustin with Martin Luther King, Jr.

in 1956 (Credit: Associated Press)

X. Conclusion

In this questioning song, Ysaye Maria Barnwell of Sweet Honey In The Rock puts the issue before us across time and categories. The song calls to attention how too many of us see others in categories with a question of whether they are worthy to share space as neighbors and family members. And importantly, if I knocked on your door needing shelter from those who think that I should not be, would you “harbor me”?

Would You Harbor Me?

Would you harbor me?

Would I harbor you?

Would you harbor me?

Would I harbor you?

Would you harbor a Christian, a Muslim, a Jew, a heretic, convict, or spy?

Would you harbor a runaway woman or child, a poet, a prophet or king?

Would you harbor an exile, or a refuge, a person living with AIDS?

Would you harbor a Tubman, a Garrett, a Truth, a fugitive or a slave?

Would you harbor a Haitian, Korean, or Czech, a lesbian or a gay?

Would you harbor me?

Would I harbor you?...13

Notes

1. Harper, Douglas. Online Etymology Dictionary. Online location: http://www.etymonline.com/ accessed 9 March 2011

2. “Stranger Blues.” By Sweet Honey In The Rock. Give Us Your Poor. West Chester, PA: Appleseed Records, 2004.

3. Online location: http://www.genderspectrum.org/ accessed 9 March 2011

4. “Just as I Am.” By Charlotte Elliot. African American Heritage Hymnal. Chicago, IL: GIA Press, 201. #344

5. Keith Boykin. “Gays in the Village. Online location: http://www.thenewblackmagazine.com/view.aspx?index=491 accessed 9 March 2011

6. “Standing in the Need of Prayer.” Negro Spiritual. African American Heritage Hymnal. #441

7. Delano Squires. Posted March 3, 2011 Online location: http://www.theroot.com/views/black-church-and-lgbt-community?page=0,1 accessed 9 March 2011

8. Yusef Najifi. Online location: http://www.metroweekly.com/news/?ak=4145 accessed 9 March 2011

9. Victoria Diane Kirby. Online location: http://isites.harvard.edu/icb/icb.do?keyword=k78405&pageid=icb.page414497

10. Interview with Bishop Rainey Cheeks. Online location: www.portofharlem.net/ accessed 9 March 2011

11. “I’m Gonna Eat at the Welcome Table.” African American spiritual and Freedom song.

12. Bayard Rustin. Online location: http://rustin.org/?page_id=3 accessed 9 March 2011

13. “Would You Harbor Me?” ©1994. Written by and used with permission from Ysaye M. Barnwell.