Cultural Resources

WATCH NIGHT

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Friday, December 31, 2010

Jonathan Langston Chism, Guest Cultural Resource Commentator

African American Religion Doctoral Student, Rice University Department of Religious Studies, Houston, TX

I. Historical Background and Documents

Numerous African American Christians observe Watch Night in a variety of ways; however, many may not be cognizant of the tradition’s historical roots. The precise origin of Watch Night has been disputed. Did the tradition originate in 1733 with the Methodist Movement or in the 1862 Freedom’s Eve celebrations? Though some African American Methodists can proudly pinpoint the 1733 origin of the tradition, Freedom’s Eve likely has the strongest link to the widespread celebration of Watch Night in several African American Christian churches.

In their denomination’s manuals, African American Methodists can trace the original roots of Watch Night to the Methodist tradition. The first Watch Night service began with the Moravians, “a small Christian denomination whose roots lie in what is the present day Czech Republic” in 1733 on the estates of Count Nicholas von Zinzendorf in Hernhut, Germany.1 John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist Movement, picked up the tradition from the Moravians and incorporated it into Methodism as a time for Methodists to renew their covenant with God and to contemplate their state of grace in light of the second coming of Christ. Wesley believed that all Christians should reaffirm their covenant with God annually.2 He held Watch Night services between 8:30 p.m. and 12:30 a.m. on the Friday nearest the full moon and on New Year’s Eve.3

The first Methodist Watch night service in the United States probably took place in 1770 at Old St. George’s Church in Philadelphia, a church of which Richard Allen, the founder of the African American Episcopal church, was a member.4 African American Methodists celebrated Watch Night prior to Freedom’s Eve because Allen and other African Americans celebrated Watch Night Meeting services at St. George’s Church and also at Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia.5

While acknowledging the Methodist starting point, many African American Christians link their celebration of the tradition to December 31, 1862, “Freedom’s Eve.” After the Union Army was victorious at the Battle of Antietam on September 22, 1862, Lincoln issued a preliminary proclamation that declared that all slaves in “any state or designated part of a state . . . In rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”6 Many blacks in the North and South as well as both free and enslaved blacks anxiously waited for Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation to become effective on January 1, 1863. The Sunday before that “Day of Days,” Frederick Douglass expressed to his audience at Rochester’s Spring Street AME Zion Church his elation at “the glorious morning of liberty about to dawn upon us.”7 On December 31, 1862, Watch Night services occurred throughout the United States.

Wide alert with anticipation, many blacks dared not and perhaps could not sleep throughout the late night hours because they wanted to watch “the night turn into a new dawn.”8 As they watched, many slaves reflected on their hardships and toils, mourned the memory of their ancestors and loved ones who died in slavery, and exuberantly thanked and praised God for allowing them and their descendants to watch the night of captivity pass.9

Nearly one hundred and fifty years after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, many African American Christians continue the tradition of gathering into mainline Protestant churches on New Year's Eve to celebrate Watch Night. During their Watch Night services, many African Americans probably do not specifically celebrate Freedom’s Eve per se in the sense of reflecting on their ancestors’ freedom from slavery. Yet, the direct link between Freedom’s Eve celebrations and Watch Night undoubtedly has both explicit and implicit impact on many African American Christians’ observance of the tradition. Many African American Christians consistently bring in the New Year inside of a church, starting their service between 7:00 p.m. and 10:00 p.m. On one hand, some African American worship leaders fully honor the Freedom’s Eve tradition during Watch Night. On the other hand, many African American Christians from various denominations including Methodist, Baptist, and Pentecostal churches implicitly reflect the spirit of Freedom’s Eve celebrations by bringing in the New Year with jubilation and praise, praying, shouting, and thanking God for allowing them to live and survive another year as they anticipate the fulfillment of their hopes and God’s promises in the New Year.

II. Cultural Response: Watching for Freedom in the Twenty-First Century

Giving his renowned “I Have a Dream” speech one hundred years after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, Reverend Dr. Martin King began by reflecting on Lincoln’s signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. He declared, “This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.”10 He boldly continued to exclaim:

But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languishing in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land.11

The chains of poverty, racism, and discrimination have acted as constricting shackles for many blacks throughout the course of the century following emancipation. Being only quasi-free and given the illusion of equality, many African Americans derived hope from the well spring of their faith as they struggled for the realization of God’s perfect will for true liberation and justice.

As I reflect on the historical and contemporary significance of Watch Night for African American Christians, I find myself wrestling with the following questions: should black Christians continue to keep the memory of slavery alive in the twenty-first century? Is there value to entering a New Year by reflecting on how our enslaved ancestors waited and watched for their freedom? One hundred and forty-seven years after the first Freedom’s Eve celebration, do African Americans still need to watch for freedom? How can African American faith communities watch for freedom in the twenty-first century? Throughout African American history, African Americans have offered different responses and continue to express diverse opinions to these types of questions.

Less than a decade after the first Freedom’s Eve celebration, many blacks had become resistant to celebrating Freedom’s Eve and Emancipation Day.12 Many African Americans wanted “to distance themselves from the more painful and degrading aspect of the race’s collective past,” as they felt that celebrating blacks’ emancipation kept the memory of slavery alive.13 After 1870, and even continuing into the twentieth century, many African Americans advocated halting Freedom Day commemorations.14 In 1876, Theophilus G. Steward, an AME minister, insisted that “blacks would never unite behind a ‘common history’ because the race’s history was centered on slavery, and ‘slave history is no history.’”15 In his series of essays on the social life of blacks in New York City, Steward explained that it was difficult “to find a colored man even from the South who will acknowledge that he actually passed through the hardships of slavery … Men do not like to be referred to slavery now.”16

Despite the early resistance to celebrating blacks’ emancipation, many African American Christians have continued the tradition of gathering in churches for Watch Night services. As the slaves did on Freedom’s Eve, many black Christians offer prayers of thanksgiving, sing praises, shout, dance, and “get happy” as they transition from one year into the next. With high hopes and expectations for bountiful blessings, many watch and pray as the clock strikes midnight.

However, in my experience and celebration of Watch Night in a Church of God in Christ congregation, a Baptist church, and in a United Methodist church, the emancipation thrust of Freedom’s Eve has had weak emphasis. Unlike enslaved blacks, during my celebrations of Watch Night in the twenty first-century, I must acknowledge that I have not devoted time to prayerfully reflecting on the glorious dawning of freedom for enslaved persons and communities. Similar to millions of Americans, I have established personal New Year’s resolutions, vowing to liberate myself from unwelcome habits, to clear my debts, to eat healthier and to exercise regularly. I certainly have frequently watched for freedom for myself and my family. But faithfully watching for the coming of freedom for dilapidated African American communities and oppressed persons throughout the world has not explicitly been a point on the agenda of Watch Night services that I have attended.

As Reverend Steward explained over a century ago, many contemporary African Americans may not feel the need to continue watching for freedom. Some may contend that Blacks are far removed from the evil days of slavery. Dr. King’s position that “the Negro is still not free” is nearly half a century old; and since then, undeniable progress has been made in the struggle for freedom. Black Americans have the freedom to own property and to obtain lucrative wealth in a free capitalistic market economy, to acquire an education, and even to become the president of the United States. To say that black Americans like the well-known Irvin “Magic” Johnson, Tiger Woods, and Michael Jordan are financially free is an understatement. Black Americans are living the American dream as doctors, lawyers, engineers, college professors, etc. Black Americans have passed through academic halls in both predominantly black and white institutions. Though a minority, blacks are sitting in some of the highest offices in judicial, legislative, and executive branches of government. Hence, some persons may question if there are any rational justifications for black churches to continue the African American tradition of watching for freedom. Slavery is in the past, and blacks are free.

Unfortunately, even 147 years after the Emancipation Proclamation there is ample room for blacks to watch for freedom in the United States. There are a number of staggering disparities in healthcare, public and private education, employment, wealth, and the justice system between black and white Americans. Thousands of black Americans are in bondage to drug addictions and substance abuse, including alcohol, marijuana, crack and cocaine. Marian Wright Edelman and many other persons have insisted:

Imprisonment is the new slavery for the black community … Of the 2.1 million inmates today, 910,000 are African American. Blacks make up 43.9% of the state and federal prison populations but only 12.3% of the U.S. population … African Americans constitute 13% of all monthly drug users, but they represent 35% of arrests for drug possession, 55% of convictions, and 74% of prison sentences.17

Furthermore, there is room for freedom for all children, especially minorities. Since 1973, the Children’s Defense Fund has campaigned for adequate health coverage for all children, to protect children from abuse and neglect, to promote equal access to quality education, and to end child poverty and the cradle to prison pipeline that funnels too many youth down the path to prison.18 Certainly African American churches can continue to watch for freedom. During Watch Night, African Americans can praise God and celebrate the progress that has been made in the freedom struggle, and they can renew their hope and faith in God to face the challenges that lie ahead. African Americans can watch with anticipation that the complete promise of freedom will be fulfilled. Black Christians can be inspired by the prophet Jeremiah’s words to the people of Israel, “For surely I know the plans I have for you, says the Lord, plans for your welfare and not for harm, to give you a future with hope” (Jeremiah 29:11, NRSV).

III. African American Traditional Songs

The following traditional hymns can aid African Americans in reflecting on how God has been and remains to be their source of hope in the freedom struggle. Written by Albert A. Goodson, “We’ve Come This Far by Faith” is a congregational hymn that can encourage African Americans to cogitate how far they have come in America from the era of slavery to the present. The lyrics of “How I Got Over,” an African-American hymn written by Reverend C. H. Cobbs, can also inspire African Americans to anticipate victory in the freedom struggle. Cobb imagines one day entering paradise and looking back and pondering, “How I got over?” Not only can getting over be a referent to heaven but it also can be a referent to the realization of earthly hopes and dreams. “O God, Our Help in Ages Past” is an English hymn written by Isaac Watts. The hymn paraphrases Psalm 90, a prayer of Moses. In this Psalm, Moses distinguishes the eternal nature of God from the finite nature of human beings. Moses muses how God has been a dwelling place and source of refuge for the children of Israel for all generations (Psalm 90:1). As they bring in the New Year, this hymn can inspire African American Christians to ruminate how God has been their sustaining power and source of security throughout the ages, their “help in ages past” and their “hope for years to come.”

We’ve Come This Far by Faith

Chorus

We’ve come this far by faith leaning on the Lord; Trusting

In His Holy Word, He’s never failed me yet.

Oh, Can’t turn around, We’ve come this far by faith.

Verse

Don’t be discouraged with trouble in your life.

He’ll bear your burdens

And move all misery and strife, That’s why we’ve

*(Optional: Recitation)

Just the other day I heard a man say he didn’t believe in God’s Word;

I can say God has made a way, He’s never failed me yet, Thank God,

We’ve come this far by faith.19

How I Got Over

Chorus

How I got over (How I got) over, my Lord, and my

Soul looked back and wondered (wondered, wondered) How I got over, my Lord.

The tallest tree (in) paradise, The Christians

Call (it) tree of life. And my soul looked back and

Wondered (wondered, wondered) How I got over, my Lord.

Lord, I’ve been ‘buked (and) I’ve been scorned, And I’ve been

Talked (‘bout as) sure as your’s born. And my soul looked back and

Wondered (wondered, wondered) How I got over, my Lord.

Oh, Jordan’s river (is so) chilly and cold, It will chill your

Body (but) not your soul. And my soul looked back and

Wondered (wondered, wondered) How I got over, my Lord.20

O God, Our Help in Ages Past

O God, our help in ages past,

Our hope for years to come,

Our shelter from the stormy blast,

And our eternal home!

Under the shadow of Thy throne

still may we dwell secure;

Sufficient is Thine arm alone,

and our defense is sure.

Before the hills in order stood

Or earth received her frame,

From everlasting Thou are God,

To endless years the same.

Time, like an ever rolling stream,

Bears all its sons away;

They fly, forgotten, as a dream

Dies at the opening day.

O God, our help in ages past,

Our hope for years to come,

Be Thou our guide while life shall last,

And our eternal home.21

IV. A Watch Night Poem

Cheryn D. Sutton of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania wrote the following poem which highlights the African American history of Watch Night. The poem can be read during Watch Night services or printed in the church bulletin as a reading.

Watch Night

The Lord will watch over your coming and going both now and forevermore. –Psalm 121:8

We gather

with quiet invocation and fervent shouts

in prayer houses built by our ancestors.

It is the anniversary of freedom’s eve,

the beginning of a new year;

and our voices ache with jubilee songs

our feet moving, our bodies possessed

our spirits remembering.

It was on New Year’s Day long ago when enslaved Africans,

their children,

and their children’s children

became irrevocably free.

of January, A.D. 1863,

all persons held as slaves

within any State

or designated part of a State

the people whereof

shall then be in rebellion . . .

The freedom words

that were woven into sweet-grass baskets,

hidden in the words of negro spirituals,

preached aloud at campground meetings,

sung to black babies in sleepy-time songs,

would become the law of the land

Alleluia.

Praise the Lord.

Then freedom’s eve became freedom’s day

(after 100 days of waiting,

three years of a bloody civil war,

more than two centuries of servitude)

as an answer to the petitioner’s plea:

How long, my Lord, how long

Truly there was a reason why,

so many were gathered

on that new year’s eve in 1862:

skins dark as the midnight sky,

or pale as the sand on a sea island beach,

Truly there was a reason why,

embraced by traditions from across the seas,

our ancestors had the griots

tell those wonderful stories of home.

Truly there was a reason why,

they created drum sounds with their feet,

their hand-claps, and their rhythm sticks;

spoke of a future free of shackles,

waited and watched till the morning came.

They trusted the words of Lincoln:

Shall be then, thence forward,

and forever free.

They believed the words of Leviticus:

It shall be a Jubilee for you

and each of you shall return to his possession,

and each of you shall return to his family.

But could they really have faith

(this time)

that the righteous would truly be blessed?

for the comings and goings of life

can never be foretold.

How long, my Lord, how long?

There was no word at midnight,

nor at daybreak,

but past dusk on New Year’s Day came a message:

tapped across telegraph wires,

spoken at great mass meetings.

The proclamation had been signed.

Emancipation was forever.

God’s chosen would be free.

It was written:

. . . upon this act,

sincerely believed to be an act of justice

warranted by the Constitution

upon military necessity

I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind

and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

Now, more than a century later,

in churches and chapels and houses of prayer,

on the anniversary of freedom’s eve,

on watch night:

we gather

to welcome yet another year;

to bring in jubilee,

Waiting anew for the midnight hour

with whispers and shouts,

singing and silence,

libations and thanksgiving.

Remembering that we were not always

Free.22

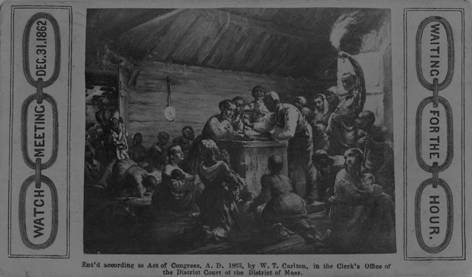

V. Visual Suggestions for Church Programs or Screens

To assist members in their Watch Night service, the worship leader may place the following in the church bulletin or on the projector screen. This image can be copied from the website on this page or from the 2008 African American Lectionary Watch Night material. Simply go to the Year One archive on the website to print it.

An Image of a Freedom’s Eve Celebration23

An audio visual clip of Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream Speech,” particularly the segment where he discusses the Emancipation Proclamation can also be used.24

VI. Annotated Resources

Some books that can aid African-Americans further exploring Watch Night include:

- Abbington, James, and Linda H. Hollies. Waiting to Go! African American Church Worship Resources from Advent Through Pentecost. Chicago, IL: Gia Publications, 2002; Bone, Daniel L., and Mary J. Schifre. Prepare: A Weekly Worship Plan Book for Pastors and Musicians. Nashville, TN:Abingdon Press, 2008.

- Kachun, Mitch. Festivals of Freedom: Memory and Meaning in African American Emancipation Celebrations, 1808-1915. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2003; Williams, William H. O Freedom!: Afro-American Emancipation Celebrations. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1987.

- Smiley, Tavis. The Covenant with Black America. Chicago, IL: Third World Press, 2006; Franklin, Robert M. Crisis in the Village: Restoring Hope in African American Communities. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2007.

These worship books provide hymns, gospel songs, scriptures, and images that can help the worship leader prepare for the watch night service.

These rich academic texts offer historical analyses and interesting illustration and photography of various African American emancipation celebrations including Freedom’s Eve, Emancipation Day, and Juneteenth.

Their works contain statistical analyses that pinpoint current challenges and complexities in African American communities and both works also contain strategic plans of action for African Americans to consider adopting and enacting to address black family, community, ecclesiastical, educational, and political breakdowns.

Notes

1. “Watch Night.” Snopes.com. Online location: http://www.snopes.com/holidays/newyears/watchnight.asp accessed 21 July 2009; Podmore, Colin. The Moravian Church in England, 1728-1760. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998.

2. “Watch Night Service.” Glossary of Terms. United Methodist Church. Online location: http://archives.umc.org/interior.asp?mid=258&GID=308&GMOD=VWD&GCAT=W accessed 23 July 2009

3. Sydnor, Calvin H. “Editorial – The Watch Meeting Night Services in Black America Began With the AME Church And Dates Back To The 1700s.” The Christian Recorder Online English Edition 12 Dec. 2008.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. Kachun, Mitch. Festivals of Freedom: Memory and Meaning in African American Emancipation Celebrations, 1808-1915. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2003.

7. Ibid.

8. Jaynes, Gerald D., ed. Encyclopedia of African American Society. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2005. p. 870.

9. Ibid.

10. King, Martin Luther. “I Have a Dream.” Washington, D.C. August 28, 1963. Online location: http://www.mlkonline.net/dream.html accessed 21 July 2009

11. Ibid.

12. Kachun, Mitch. Festivals of Freedom: Memory and Meaning in African American emancipation Celebrations, 1808-1915. P. 176.

13. Ibid., 148.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid., 151.

17. Smiley, Tavis. The Covenant with Black America. Chicago, IL: Third World Press, 2006, xiii.

18. Children’s Defense Fund. Online location: http://www.childrensdefense.org/ accessed 29 July 2009

19. “We’ve Come This Far by Faith.” The New National Baptist Hymnal.Nashville, TN: National Baptist Publishing Board, 1984, 1977. p. 222.

20. “How I Got Over.” The New National Baptist Hymnal. P. 266.

21. “O God, Our Help in Ages Past.” The New National Baptist Hymnal. P. 19.

22. “A Watch Night Celebration: New Year’s Eve.”See Behold, a New Thing for “Ideas for Celebrating a Service of Watch Night; The Tradition of Watch Night; How to Explore Watch Night.” Online location: http://www.ucc.org/worship/worship-ways/pdfs/2007/07Behold-A-New-hing.pdf accessed 21 July 2009

23. Download picture of “Watch Night, 1862.” Hungry Blues. Net.

http://hungryblues.net/wp-content/uploads/2006/09/watchnightservices.JPG accessed 16 July 2009.

24. King, Martin Luther. “I Have a Dream” video clip. Online location: http://www.mlkonline.net/video-i-have-a-dream-speech.html accessed 21 July 2009.