Cultural Resources

KWANZAA

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Sunday, December 26, 2010 - Saturday, January 1, 2011

Juan M. Floyd-Thomas, Lectionary Team Cultural Resource Commentator

I. History Lesson

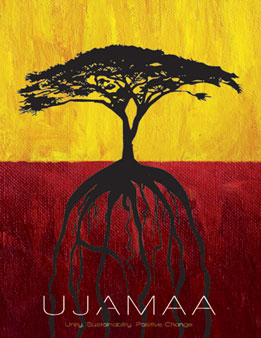

Since its inception in 1966, Kwanzaa has been a weeklong celebration in the United States. Held from December 26 to January 1, it honors the history, heritage and faith of women, men and children of African descent. It is marked by participants lighting the kinara (African inspired candle holder), pouring libations, partaking in a communal feast and exchanging gifts. Dr. Maulana Karenga, a pioneering professor of Black Studies at California State University at Long Beach, first created the weeklong festival from December 26, 1966 to January 1, 1967. The Nguzo Saba (The Seven Principles of Kwanzaa) are Umoja (unity), Kujichagulia (self-determination), Ujima (collective work and responsibility), Ujamaa (cooperative economics), Nia (purpose), Kuumba (creativity) and Imani (faith).

This was an historic event because it represents the first occurrence of a holiday specifically focused on African American history and heritage in United States history. Karenga said his goal was to "give Blacks an alternative to the existing holiday and give Blacks an opportunity to celebrate themselves and history, rather than simply imitate the practice of the dominant society." Kwanzaa has been observed annually and has gained a considerable amount of mainstream recognition in American society.

The name Kwanzaa derives from the Swahili phrase matunda ya kwanzaa, meaning "first fruits of the harvest." According to Karenga, Kwanzaa was envisioned as being directly opposed to the gaudy commercialization of Christmas by providing an Afrocentric alternative to "European cultural accretions of Santa Claus, reindeer, mistletoe, frantic shopping, [and] alienated gift-giving." At its essential core, Kwanzaa was devised deliberately as a countercultural celebration of pan-African values, virtues, and views through a coordinated celebration of self-definition, self-determination, and solidarity for women, men, and children of African descent.

II. Kwanzaa’s Significance Now

that it pains [me] that we need to look outside our American experience for spiritual and cultural sustenance. With all due respect to those who celebrate it, Kwanzaa feels like a cop-out… My objection is not that Kwanzaa is “made up.” What observance isn't? My problem is its rejectionist nature. Certainly, some celebrate both Kwanzaa and Christian holidays. Also, some celebrate Kwanzaa affirmatively, as a way of honoring the African ancestors who were taken from us and of mourning the lives we were prevented from living. Too often, though, Kwanzaa feels as if it is more about thumbing black noses at white America than at embracing the lost cause of resuming our Africanness.1

Given Dickerson’s contrarian perspective on American race relations, I was more than ready to chalk up this commentary to the combination of her acerbic, often cranky, witticisms and the desperate self-denial for the sake of mainstream assimilation until reading Erin Evans’ article in The Root. Unlike Dickerson, who came to the celebration of Kwanzaa later in life and with her idiosyncratic critique of overtly Black-identified matters, Ms. Evans’ essay, “The Trouble with Kwanzaa,” comes from a somewhat different space in terms of cultural resonance and consciousness. Beginning with the sentence, “OK, this may not be politically correct to say, but I just don't get what's up with Kwanzaa,” Evans engages in a personal account wherein, steeped in a “post-everything” reality, she is literally mystified by the meaning and merits of this holiday despite having celebrated it during her childhood. Even though she seems to cognitively understand why Dr. Karenga and other Black Power advocates felt the necessity to bring forth a celebration that matched the era’s emphasis on Black cultural aesthetics and the pride it instilled, Evans’s autobiographical observations are fueled by her witnessing the morphing of Kwanzaa into a capitalist cash cow. As she states the case:

By the '90s, Kwanzaa had fallen prey to commercialism and all the good and bad that comes with it. Multiculturalism in mainstream institutions helped increase the visibility and awareness of Kwanzaa; but then came the Kwanzaa kitsch. McDonald's had a Kwanzaa commercial. Hallmark's Mahogany line had greeting cards. Kmart and Wal-mart started selling Kwanzaa gifts, cards and wrapping paper. The Kwanzaa [U.S. postage] stamp came along in 1997. There were Kwanzaa celebration pop-up books. Cartoon shows on Disney and Nickelodeon had their obligatory Kwanzaa episode, where the black character has to explain to the white ones what this seven-day ceremony is all about. All the attention, perhaps, turned a good thing bad. It just got jumbled into all the other holidays that dominate in December. Chrismahanukwanzakah, anyone?2

As she tries to shed light upon the growing fog of confusion surrounding the holiday by asking random folks to define the feast and its history, the great concern that pervaded her examination of the matter is that multiculturalism has rendered the need for culturally specific events all but irrelevant in the United States today.

At its core, the piece reflects the faltering memory and pernicious level of delusion amongst a younger generation of African Americans who believe that race no longer matters. Moreover, there is a sense amongst many youth (and even some older folks as well) who want things both ways. As such, there is a sense of titillation and excitement around the styles and symbolism of Afrocentric art, music, food, and other cultural manifestations surrounding Kwanzaa yet they want nothing to do with the political realities and liberated worldview that brought the holiday into being.

This, however, represents a clear paradox: how can Kwanzaa as a holiday be seen as accessible when the political roots and spiritual origins of the celebration are deemed as anachronistic? What observers such as Dickerson and Evans missed about the brilliance of Karenga’s creation of Kwanzaa is that, regardless of the holiday’s recent move towards rampant commercialism, this weeklong festival was conceived in the midst of a cultural revolution with the intent of cultivating relationships. Although Kwanzaa--much like the various other manifestations of the Black Power era--was initially focused on rearranging the existing social hierarchy and accompanying power dynamics along racial lines, the most constructively meaningful realignment portended by Karenga's brainchild was to imagine a way for Black people to emphasize and ultimately appreciate their African roots in a positive rather than pessimistic fashion. In this sense, Kwanzaa was never solely about tearing down dominant Eurocentric ideologies and power structures (although that is hugely important) but also focused on building up Black families, institutions and communities rooted in the transcendent knowledge that we are capable of being and doing more together than we ever could imagine achieving separately.

III. A History Document

Dr. Maulana Karenga, “Annual Founder’s Kwanzaa Message 1966— 43rd Anniversary— 2009--, Principles and Practices of Kwanzaa: Repairing and Renewing the World.”

The core message and expansive meaning of Kwanzaa is rooted in its role as a rightful and joyous celebration of family, community and culture. Indeed, it is a celebration of a people in the rich and complex course of their daily lives and in the midst of their awesome and transformative movement thru human history. It is a holiday that grew out of the ancient origins of first-fruit harvest festivals which celebrate the abundant good of life and all living things and the good of earth itself and all in it. It rises also out of our modern struggle for an inclusive freedom, a substantive justice, a dignity-affirming equality, and a life-enhancing power of our people over our destiny and daily lives. And it bears the mark and message of both models and movements.

It is this ancient, fertile and constantly cultivated soil and source of our culture that explain the extraordinary and constant growth of Kwanzaa throughout the world African community. Surely, Kwanzaa would not have lasted if it had simply been a seasonal trend, a consumerist fad or the purchasable product of a corporate-cultivated consciousness. More-over, its resilience and relevance, like its origins and future, do not lie in official approval, presidential greetings or govern-mental recognition and endorsement by resolution on any level.

Rather Kwanzaa was conceived, created and introduced to the African community as an audacious act of self-determination, a cultural creation that is rooted in and rose out of the wish and will of a people who saw its message deep in meaning, world-encompassing in reach, highly relevant in addressing critical issues of our time and the practice of its principles, as a valuable way to ground, guide and enrich their lives.

Each Kwanzaa we are called upon to think deeply about our lives and the world, and ask ourselves how do we as a person and people understand ourselves and address the critical issues of our times in ethical and effective ways. Then, we are to recommit ourselves to our highest ideals, our best values and visions, and to a sustained and transformative practice of these principles. And at the heart and center of Kwanzaa are the Nguzo Saba, The Seven Principles.Indeed, the Nguzo Saba offer us a foundation and framework to address issues of our time thru both principles and practices, a unity which cannot be broken without damaging and diminishing them both. This means prefiguring in our daily lives and practices the good world we all want and deserve to live in, and it requires constant reflection on and practicing the Nguzo Saba and interrelated values directed toward bringing good in the world.

Surely, in a world ravaged and ruined by war, defined by division, oppression and varied forms of greed, hatred and hostility, the principle of Umoja (Unity) invites an alternative sense of solidarity, a peaceful togetherness as families, communities and fellow human beings. It teaches us the oneness of our people, everywhere, the common ground of our humanity with others and our shared status as possessors of dignity and divinity. But it also encourages us to feel at one with and in the world, to be constantly concerned about its health and wholeness, especially as we face the possibility of climate change and other disasters around the world.

In a time in which occupation and oppression of countries and peoples are immorally presented as necessary and even salvational, the principle of Kujichagulia (Self-Determination) rejects this and reaffirms the right of persons and peoples to determine their own destiny and daily lives; to live in peace and security; and to flourish in freedom everywhere. In opposition to alienation and isolation from others, fostered fear and hatred for political purposes, and a vulgar individualism at the expense of others, the principle of Ujima (Collective Work and Responsibility) teaches us the necessary and compelling commitment to work together to conceive and build the good community, society and world we want and deserve to live in. And this means cooperatively repairing and renewing the world.

In a world where greed, resource seizure, and plunder have been globalized with maximum technological and military power, we must uphold the principle and practice of Ujamaa (Cooperative Economics) or shared work and wealth. This principle reaffirms the right to control and benefit from the resources of one’s own lands and to an equitable and just share of the goods of the world. In a world where there is an urgent need to move beyond petty and perverse purposes and narrow and narcissistic concerns, the principle and practice of Nia (Purpose) provides us with an expansive ethical alternative. For it teaches us the collective vocation of bringing, increasing and sustaining good in the world, and insuring the well-being, health and wholeness of the world.

In a world where war lays waste the lands and lives of the people, where depletion, pollution and plunder of the environment put the world at risk and climate change threatens devastating hurricanes, floods, famine, millions more of refugees and the submersion by rising seas of whole communities and nations, the principle and practice of Kuumba (Creativity) is imperative. For it puts forth the ethical ancestral teaching from the Husia of serudj ta, the moral obligation to do all we can in the way we can to heal, repair, rebuild, and renew the world, leaving it more beautiful and beneficial than we inherited it.

Finally, in our world and time when words of hope and change evaporate into business as usual, when peace is postponed for war, social programs put on hold, bankers bailed out and the poor erased from the agenda, Imani (Faith) offers a shield against despair, cynicism and paralyzing disappointment. Faith calls us to believe in the good we seek to create, to work for it, and to live it in our daily lives. Indeed, only in this way will we be able to repair and renew ourselves in the process and practice of repairing, rebuilding and renewing the world.

In the spirit of the steadfast faith of our ancestors, let us meditate on and give ever-deeper meaning in actual practice to this Kwanzaa wish of good and prayerful request of our ancestors: May we speak truth and do justice everywhere. May we always evaluate rightfully and not act in disregard of the sacred and the people. May we enter praised and leave loved everywhere we go. May our speech be wholesome and without blame or injury to others. May we reject evil and embrace joy. May we live a lifetime of peace. And may we pass in peace having done Maat and brought good in the world.

Heri za Kwanzaa (Happy Kwanzaa).3

IV. Making It a Memorable Learning Moment

Although Christmas and Kwanzaa are literally one day behind the other, we strive to maintain a healthy balance between both holidays. In our household, there has been no conflict or contradiction in celebrating Kwanzaa because we strive to emphasize the dimensions of family and community that animated Dr. Karenga’s original intention behind creating the celebration. Part of the way that we adapt the structure of the celebration to match the central concerns of elevating our cultural heritage and communal concerns is by hosting a ceremonial gathering that encapsulates all of the elements of Kwanzaa in one event.

I suggest that you begin planning for your Kwanzaa gathering by the last week in November—about the same time we start decorating the house for Christmas—by making sure you have the following items: the Kinara (candle holder) to hold the Mishumaa saba [seven candles—one black (for our race), three red (for the struggle), and three green (representing hope)]; Mkeka (placemat preferably made of straw); Mazao (fruits and vegetables representing the “first fruits” of the harvest); Vibunzi/Muhindi (ears of corn in order to reflect the number of children in the household and they can be biological, adopted, or children you have helped rear); Kikombe cha umoja (communal unity cup); and Zawadi (gifts that are enriching). When we circulate invitations to friends, family, and neighbors, they usually include the following words: Honoring our past ~ Celebrating our present ~ Anticipating our Future!

My wife and I assign our guests one of the seven principles and instruct them to get gifts that reflect the principle they were given. On the evening of December 26, we have a dinner gathering that has a full family-style buffet meal prepared with seven dishes that reflect each of the elements of the Nguzo Saba. After spending an hour or so eating, drinking, and socializing, we move to the room decorated for the occasion. In that setting, the eldest member of the group shares his/her perspective on why it is important that we gather together in this manner. Then we proceed to ask everyone to make a statement based on their reflection on their assigned principle from the Nguzo Saba, lighting the appropriate candle (the kinara), and then exchanging gifts with each other.

After that, we close the evening in prayer and then return to the festivities. Rather than enacting a ritual that is stoic and self-conscious, this adapted approach to the celebration concentrates on the notion that we need to connect with one another not just for political or economic purposes (even though that is important) but because we are spiritual beings who are divinely created to relate to one another in ways that recognize our common humanity and try to imagine our shared destiny.

V. Audio Visual Aids

The first documentary on Kwanzaa, The Black Candle, is a film by M.K. Asante Jr., the son of leading Afrocentric scholar, Molefi Kete Asante, Sr. The younger Asante serves as the film's writer, producer and director. Narrated by renowned author and Poet Laureate Maya Angelou, the documentary highlights the celebration's seven principles and delves deeply into history to give Kwanzaa's purpose and meaning a serious backdrop. The film lovingly focuses most intently upon the holiday as a celebration of Black family, community, and culture. Asante’s film interviews hip-hop pioneer Chuck D, poet and publisher Haki Madhubuti, activist and poet Amiri Baraka, football great, movie star and civil rights activist Jim Brown and, most importantly, Maulana Karenga, the founder of Kwanzaa to provide historical and social context regarding how the holiday began to gain momentum within the mainstream.

The Black Candle is a memorable as well as mesmerizing glimpse of the evolution of Kwanzaa in its present-day development as a pan-African holiday celebrated by more than 40 million celebrants worldwide that offers at least one festive link to bridge the proverbial generation gap between the hip-hop and the civil rights generations, illustrated by everything from archival footage of the civil rights movement to rousing scenes of a Kwanzaa celebration being hosted in France. For more details, visit The Black Candle website’s online location: http://theblackcandle.com/.

VI. Sources of Gaining and Enhancing Knowledge of Kwanzaa

1. Karenga, Maulana. Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture. Los Angeles, CA: University of Sankore Press, 2008. Online location: www.sankorepress.com accessed 1 January 2010

2. Riley, Dorothy W. The Complete Kwanzaa: Celebrating Our Cultural Harvest. Castle Books, 2003.

3. Katz, Karen. My First Kwanzaa. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Co., 2003.

4. Mayes, Keith A. Kwanzaa: Black Power and the Making of the African-American Holiday Tradition. New York and London:Routledge, 2009.

5. The African American Holiday of Kwanzaa. Videocassette. Los Angeles, CA: University of Sankore Press. Online location: www.sankorepress.com accessed 1 January 2010.

6. “Nguzo Saba: The Seven Principles of Kwanzaa.” Online location: http://aalbc.com/kwanzaa.htm accessed 1 January 2010

7. “A Kwanzaa Keepsake.” Online location: http://aalbc.com/akwanza.htm accessed 1 January 2010

8. Melanet's Kwanzaa Information Center.

9. The Official Kwanzaa Web Site. Online location: http://www.officialkwanzaawebsite.org/ accessed 1 January 2010

10. Kwanzaa! African Lives in a New World Festival. AALBC recommended book. Online location: http://aalbc.com/kwanzaa!.htm accessed 1 January 2010

Notes

1. Dickerson, Debra J. “A Case of the Kwanzaa Blues.” The New York Times 26 Dec. 2003. Online location: http://www.nytimes.com/2003/12/26/opinion/a-case-of-the-kwanzaa-blues.html accessed 1 January 2010

2. Evans, Erin E. “The Trouble with Kwanzaa.” The Root 22 Dec. 2008. Online location: http://www.theroot.com/views/trouble-kwanzaa accessed 1 January 2010

3. Karenga, Maulana. “Principles and Practices of Kwanzaa: Repairing and Renewing the World.” Los Angeles Sentinel 24 Dec. 2009: A7. Online location:

http://www.officialkwanzaawebsite.org/documents/PrinciplesandPracticesofKwanzaa_000.pdf

accessed 1 January 2010