Cultural Resources

SECOND SUNDAY OF ADVENT

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Sunday, December 6, 2009

Riggins R. Earl, Jr., Guest Cultural Resource Commentator

Professor of Ethics and Theology at the Interdenominational Theological Center, Atlanta, GA

I. Introduction

Matthew’s Gospel tells a marvelous story of John the Baptist being the precursor of Jesus’ ministry, as an ordained voice crying in the wilderness. As narrator of the story, Matthew notes that John challenged the waiting generation of his day to ready itself properly (i.e., by repenting, confessing and being baptized) for the Lord’s advent. For Matthew, John’s message had both a priestly and prophetic ring to it, harking back to the sacred traditions of the Old Testament. According to Matthew’s narrative, John the Baptist’s message provokes two types of group responses from his generation: a) the repentant, confessional, and obedient group type response, symbolized by those who came to be baptized by John, and b) the rebellious, fugitive, deceitful group type response, symbolized by many of the Pharisees and Sadducees. The latter undoubtedly concluded that they had come to see no more than a wilderness buffoon.

This particular biblical passage of John’s message to his generation provokes such questions as: How do you prophetically and in a priestly way challenge a waiting oppressed people to prepare ritualistically (i.e., by “repenting,” “confessing,” and “being baptized”) for the coming of their liberator? How do you prophetically and in a priestly manner challenge oppressors to prepare ritualistically (i.e., by “repenting, “confessing,” and “being baptized”) for the advent of the Lord and Judge of them and their systems of injustice?

How does the prismatic character of the black experience hermeneutically illuminate such biblical notions as “waiting,” “readying,” “repenting,” “confessing” and “being baptized?” The prismatic character of the black experience as a cultural commentary resource richly illuminates this passage. Many black preachers of America have modeled their identity after John the Baptist’s pattern of being a “voice crying in the wilderness.” They counted such an identification/association with John the Baptist an honor.

II. John the Baptist as a Voice and Black Preachers as a Voice

In Dallas, Texas, community leaders marked the 92nd birthday on December 17, 2006 of Pastor Caesar Clark, affectionately known as “Little Caesar.” Clark, before he died in 2009, pastored the Good Street Baptist Church for fifty-five years. At the birthday celebration, Dr. C.B.T. Smith, Clark’s lifelong friend, interestingly linked Clark’s preaching legacy with that of John the Baptist. Smith, who was only one year younger than Clark, referenced John the Baptist as the identity model for black preachers of an earlier generation. Smith noted that Clark and himself were “. . . from a fading, less political era of preachers who patterned themselves after John the Baptist’s singular message.” Smith continued in his remarks to Clark and those gathered for the celebration: “John said, ‘I am a voice crying in the wilderness.’ When any minister can get to the place where he is a voice . . . he’s a preacher par excellence. That is where you are today. Happy birthday.”1

Smith’s laudatory words provide a rather interesting perspective of how previous generations of black preachers authentically identified with John the Baptist’s personality, preaching style and message content. In an era when many contemporary popular black preachers assign themselves such elite bureaucratic titles as bishop and apostle, Smith challenges us to envy and embrace a very primal biblical notion of the preacher’s identity, i.e., that of “a voice.”

Black cultural commentary resources, both of a scholastic and folksy nature, of this scriptural text (Matthew 3:1-12) continue to grow. They show how black people have associated black preachers’ identities with that of John the Baptist’s. The genesis of the making of these sources started with slaves being converted to the Christian gospel and taking up the mantle of preaching it. A gradual contemporary growth of black cultural commentary resources must be attributed to the increase of black biblical scholars in the last several decades. These scholars’ published works continue to fill what has been a menacing void in the literature regarding Africans’ presence in the world of the Bible. Fortunately, black cultural commentary resources are now available in both written texts and film narratives.

The annotated notes on Matthew 3:1-12 in The Original African Heritage Study Bible link John the Baptist to the world of Africa: “John the Baptist was an Afro-Asiatic or Edenic wilderness prophet who Luke’s Infancy narrative goes so far as to suggest was a close relative of Jesus (Luke 1:36).”2 Although he makes no reference to John’s ethnicity, Michael Joseph Brown’s commentary on the passage is instructional because it accents the social justice aspect, which is often ignored by biblical interpreters, of John’s message. Brown notes that John’s message calls for social transformation as a whole under the rule of God (Matt., 3:1-2).3

III. Forerunner Voices

Extra-biblical cultural commentary resources in the black tradition are no less illuminating of this passage. This is very transparent when we parallel John the Baptist’s precursor role in the ministry of Jesus with that of Dr. Vernon Johns’ in the ministry of Martin L. King, Jr. The American black community concluded in hindsight that Dr. Vernon Johns, who was the pastoral predecessor of Dr. Martin L. King, Jr. at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church of Montgomery, was King’s prophetic forerunner. Dr. Vernon Johns was God’s ordained, prophetic and priestly “voice crying in the wilderness” of segregated America. Vernon Johns dared challenge the community of Montgomery to make straight the path of the Lord. Unconsciously, Johns was readying the black community of Montgomery and America for the coming of Martin L. King, Jr. Johns’ message was one of challenging his generation to make ready for the Lord of social transformation.

Extra-biblical cultural commentary resources in the black tradition are no less illuminating of this passage. This is very transparent when we parallel John the Baptist’s precursor role in the ministry of Jesus with that of Dr. Vernon Johns’ in the ministry of Martin L. King, Jr. The American black community concluded in hindsight that Dr. Vernon Johns, who was the pastoral predecessor of Dr. Martin L. King, Jr. at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church of Montgomery, was King’s prophetic forerunner. Dr. Vernon Johns was God’s ordained, prophetic and priestly “voice crying in the wilderness” of segregated America. Vernon Johns dared challenge the community of Montgomery to make straight the path of the Lord. Unconsciously, Johns was readying the black community of Montgomery and America for the coming of Martin L. King, Jr. Johns’ message was one of challenging his generation to make ready for the Lord of social transformation.

Taylor Branch’s historical portrait of Vernon Johns, forged out of the rich treasure trove of the black oral tradition, is a must read.4 Branch’s written text was put to a film, titled “The Vernon Johns Story: The Road to Freedom.” James Earl Jones gives life to the story of Vernon Johns. The film narrative accents Vernon Johns’ semi-ascetic life style, fiery temperament and uncompromising message of corporate repentance, all of which mirrored that of John the Baptist.

IV. Waiting, Repenting, Confessing and Submitting in the Black Experience

Black people, both of the slave and colonial legacy, have continuously found the challenge of waiting and readying themselves for their liberation very problematic. Cultural commentary resources of the black experience abound for illuminating this problematic element. The abundance of the resources themselves point to the theological and moral richness of the black experience. For instance Langston Hughes, who was a premier poet, noted how an uncreative type of waiting on the part of blacks defers their dreams and hopes of freedom and ultimately results in their ruination. Hughes likens the death of the deferred dreams and hopes of the oppressed to spoiled meat and fruit in the hot sun.

What Happens to a Dream Deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore--

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over--

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

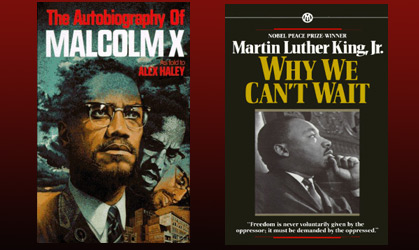

Several excellent black cultural resources illuminate the idea of creative waiting or, as Martin Luther King, Jr. termed it, “redemptive waiting.” This type of waiting was seen as an antidote to the destructive type of waiting bred by slavery. Both The Autobiography of Malcolm X and Martin L. King Jr.’s book, Why We Can’t Wait, provide commentaries on the high cost of unconstructive waiting. Insights from these sources challenge American society to take the preparatory ritualistic steps of “repentance,” “confession,” and “humility” which John the Baptist deemed imperative. John the Baptist saw these preparatory ritualistic steps as the prerequisite for the society readying itself for its coming salvation. These sources are also critical for challenging corporate and individual “rebellion,” “flight,” and “deception,” all of which interferes with the coming of the community’s salvation.

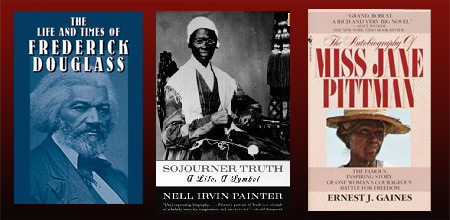

In the slave literature, stories of Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman are classical examples of former slaves, defying their oppressors’ logic of it, and redefining waiting for their liberation.7 These sources are resourceful with slave leader’s courageous belief that God was their strength in the freedom struggle. Supported by such belief, the slaves took into their own hands the freeing of themselves and their fellow slaves. In doing so, the enslaved enriched the rich abolitionist tradition.

The slave community produced another perspective of waiting which was more anchored in the biblical tradition of the Moses story. Legend has it that, at the birth of every male slave child, the question was whispered through the slave quarters: “Is he de one or shall we wait for another?” Ernest Gaines records this legend in his book, The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pitman. This mythic account of waiting on the part of the slave community projects a different theological and ethical scenario. It suggests that waiting on God for the sending of a Moses-type deliverer is a faith virtue.

V. A Less Political Notion of Waiting – Showing Hospitality

There were different theological and ethical perspectives on waiting in John’s generation. It is no less the case for blacks in America as well as different nations on the African continent and in the African Diaspora. The group known as the Zealots of Jesus’ day, who desired a political overthrow of the powers of John’s day, certainly possessed a different theological and ethical understanding of waiting for God than did the Pharisees and Sadducees.

In black cultural commentary resources, a less political idea of waiting was conveyed in the rural South’s notion of hospitality to the preacher. Poor blacks of the South deemed this a festive moment to honor the preacher and his family as the elite of God. In the movie Soul Food, Big Momma seeks to keep this tradition of feeding the preacher alive among her children in Chicago. Families hosting the minister in the rural South left no stones unturned in their preparational efforts. Senior adults, like myself, who grew up in such an era, remember the rituals of preparation, such as: a) an immaculate cleaning and ordering of the house so as to reflect the family’s affirmation of the folk belief that “cleanliness is next to godliness;” b) a careful selecting of the best family cooks for cooking the favorite Southern dishes such as fried chicken, macaroni and cheese, as well as cakes and pies. Making and serving homemade ice cream was the crowning moment of the festive event. Sometimes extended family members and a cast of supporting neighbors joined in the effort of preparation and serving; and c) children were to model their best manners. Pastors would praise the family for the meal before the congregation at the next church service.

VI. Steps to Prepare for the Coming of Christ

This communal practice of rural hospitability to the preacher accents intimacy and co-operation on the part of those waiting for the moment of his visitation. John the Baptist proposed the following ritualistic steps of preparation: a) confessing sins; b) producing of good fruits for repentance; and c) being baptized.

- Confessing Sins - For cultural commentary resources see the stories of Bishop Desmond Tutu and Nelson Mandela. Also, see the documentary Facing the Truth with Bill Moyers. Engage such theological issues as repentance, confession, truth telling, and guilt at the corporate level.

- Producing Good Fruits for Repentance. Here is an opportunity to deal with the relationship between apology and reparation.8 Apology and reparations must be seen as outward signs of the fruits of repentance.9 Discuss what it means to have one without the other.

- Being Baptized. Being baptized is ritualistic gesture, signifying humility or submission. The National Quaker Organization in America is doing some incredible work in the African nation of documenting how the people are washing entire villages so as to cleanse them from the stain caused by genocide.10 How are we baptizing the world today as we await the advent of the Christ?

Notes

1. The Dallas Morning News. April 16, 2009:1; See also, Williams, Shawn. “The Great C.A.W. Clark, pastor of Good Street Baptist Church, dies Sunday in Dallas (1914-2008)” Dallas South. 28 Jul. 2008. Online location: http://dallassouthblog.com/2008/07/28/the-great-caw-clark-pastor-of-good-street-baptist-church-dies-sunday-in-dallas-1914-2008/ accessed 20 June 2009

2. Felder, Cain Hope. The Original African Heritage Study Bible: King James Version. Iowa Falls, IA: World Bible Pub, 1993. p. 1379.

3. Brian K. Blount, Ed. True to Our Native Land: An African American New Testament Commentary. Fortress Press: Minneapolis, MN, 2007.

4. Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954-63. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 1988.

5. See, Mills, Kay. This Little Light of Mine: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1993.

6. See, Maathai, Wangari. Unbowed: A Memoir. New York, NY: Anchor Books, 2007.

7. See, Douglass, Frederick. Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. Ware, MN: Wordsworth American Library, 1998; and Gosda, Randy T. Harriet Tubman: A Buddy Book. Edina, MN: Abdo Pub. Co., 2002.

8. See, Jones, James H. Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. Free Press: Washington, D.C., 1993.

9. Brooks, Roy L. Atonement and Forgiveness: A New Model for Black Reparations. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2004.

10. Pace, Molly Bradford, Christopher Quinn, Tommy Walker, Nicole Kidman, Panther Bior, John Bul Dau, Daniel Abol Pach, and Jamie Saft. God Grew Tired of Us. Culver City, CA: Sony Pictures Home Entertainment, 2007.