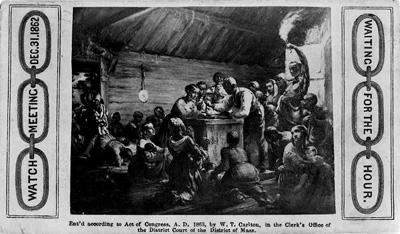

Waiting for the hour [Emancipation]

December 31, 1862

Carte de visite. Washington, 1863

WATCH NIGHT

LECTIONARY COMMENTARY

Monday, December 31, 2007

Brad R. Braxton, Lectionary Team Commentator

Lection - Isaiah 21:1-10 (New Revised Standard Version)

(v. 1) As whirlwinds in the Negeb sweep on, it comes from the desert, from a terrible land. (v. 2) A stern vision is told to me; the betrayer betrays, and the destroyer destroys. Go up, O Elam, lay siege, O Media; all the sighing she has caused I bring to an end. (v. 3) Therefore my loins are filled with anguish; pangs have seized me, like the pangs of a woman in labour; I am bowed down so that I cannot hear, I am dismayed so that I cannot see. (v. 4) My mind reels, horror has appalled me; the twilight I longed for has been turned for me into trembling. (v. 5) They prepare the table, they spread the rugs, they eat, they drink. Rise up, commanders, oil the shield! (v. 6) For thus the Lord said to me: ‘Go, post a lookout, let him announce what he sees. (v. 7) When he sees riders, horsemen in pairs, riders on donkeys, riders on camels, let him listen diligently, very diligently.’ (v. 8) Then the watcher* called out: ‘Upon a watch-tower I stand, O Lord, continually by day, and at my post I am stationed throughout the night. (v. 9) Look, there they come, riders, horsemen in pairs!’ Then he responded, ‘Fallen, fallen is Babylon; and all the images of her gods lie shattered on the ground.’ (v. 10) O my threshed and winnowed one, what I have heard from the Lord of hosts, the God of Israel, I announce to you.

I. Description of the Liturgical Moment

Watch Night is a jubilant African American worship service on New Year's Eve. While New Year's Day is a secular holiday, historic events have forever infused sacred significance into the African American celebration of the New Year.

On September 22, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln issued a preliminary proclamation, declaring that one hundred days later, January 1, 1863, slaves would be free in those states rebelling against the Union in the Civil War. On December 31, 1862, also known as "Freedom's Eve," large groups of African Americans, along with white abolitionists, gathered in meeting halls and churches across the county to watch for news that the President had formally enacted the Emancipation Proclamation. The ink with which Lincoln penned the proclamation must have been dark. Mixed in it was the blood of countless slaves sacrificed in America's ironic quest for democracy.

More than 140 years later, African American Christians continue to gather in churches on New Year's Eve to thank God for the blessings of the Old Year and to seek God's favor for the New Year.1

II. Biblical Interpretation for Preaching and Worship: Isaiah 21:1-10

Part One: The Contemporary Contexts of the Interpreter

As a second-generation African American Baptist preacher, I am no stranger to Watch Night services. In the church of my youth, where my father served as pastor, Watch Night was a well-attended joyful time of worship shared with a neighboring congregation. My home church was not especially time-conscious. Yet I remember the ministers and deacons regularly surveying the clock to ensure that the exuberant singing, testifying, and preaching not cause the waiting congregation to miss midnight. As we ushered the Old Year out and the New Year in, worshippers prayed passionately around the altar "on bended knee." Throughout the country, I knew many other African American churches were also waiting for midnight. And somewhere a preacher was asking: "Watchman, what of the night?"

A profound sense of mystery and hope filled the sanctuary during those services. While knees might have been bent around the altar, souls stood on tiptoe awaiting God to do a new thing in the New Year. The memory of my home church's Watch Night expectation sensitizes me to the profound sense of anticipation pulsating through Isaiah 21:1-10. In this text, the watcher waits eagerly for God to bring about a change.

Part Two: Biblical Commentary

Isaiah 21:1-10 pronounces the fall of the Babylonian Empire, which conquered Israel.

The passage divides into two sections: 1) vv. 1-5, and 2) vv. 6-10. In the first section, a prophet recounts the reception of an oracle and vision, which descend with the intensity of a storm (v. 1). The oracle and vision are so terrifying that they send the prophet into a state of physical and emotional turmoil, whose agony is compared to the pain of childbirth (v. 3).

Isaiah 21:2 offers a glimpse into the nature of Babylon. The prophet declares, "The betrayer betrays, and the destroyer destroys." These phrases are likely references to Babylon and reveal the tactics of betrayal and destruction that this empire used to ascend to power. Babylon's treachery creates distress and sighing among those it oppresses.

Those sighs were similar to the mournful cries of African Americans who were denied their freedom by a treacherous system of slavery. Even now, the world is full of sighing citizens. Listening with our spiritual ears, we hear sighs: from children whose parents have died from HIV/AIDS; from schoolteachers who must worry about bullets as much as books; from senior citizens unable to afford health insurance. People like this come to church wondering if anyone has heard their sighs.

In Isaiah 21:6-10, the Lord instructs the prophet to post a lookout, or watcher,

upon a tower. The watcher is to announce what is revealed. The Hebrew verb "to

announce" (nagad), frames this section and occurs prominently at the end of vv. 6 and 10. On Watch Night, the preacher should announce with hope the good things that God will do in the immediate future!

The watcher is instructed to use both eyes and ears (v. 7). The sight of an approaching army and the rhythmic cadence of horses' hooves would alert the watcher that Babylon's destruction was near. The watcher remains steadfast, occupying the watchtower throughout the day and night (v. 8). When an oppressed community anticipates divine liberation, heightened attention is necessary. In the words of the Negro National Anthem, we cannot afford to be "drunk with the wine of the world.” Our black ancestors knew there were many "intoxicants" that could cause our people—and our preachers—to fall asleep on the watch tower.

As the Lord predicted, the watcher sees the vision of the approaching soldiers who would defeat Babylon. The watcher exclaims, "Fallen, fallen is Babylon; and all the images of her gods lie shattered on the ground" (v. 9). The repetition of the word "fallen" emphasizes the certainty and finality of Babylon's collapse.

The vision also forecasts the destruction of Babylon's false gods—the supposed source of its power. As the idols and gods of a vanquished empire lie in charred rubble, the watcher references the one true God, "the Lord of hosts, the God of Israel" (v. 10).

Centuries later, early Christians appealed to Isaiah 21:9 as they prophesied the eventual destruction of another oppressive empire. In Revelation 18:2, the angel declares, "Fallen, fallen is Babylon the Great!" In that instance, "Babylon" was Rome. For African Americans in 1862, "Babylon" was the vicious system of slavery. That "Babylon" also fell. Nevertheless, "Babylon" arises in every generation to oppress people. Yet our hearts should not be troubled. God always has the final say!

Celebration

The good news is that God hears the sighs of oppressed people and has promised to bring those sighs to an end (v. 2). Also, all empires ("Babylon") and unjust social structures will eventually fall and be subject to the judgment of God.

Descriptive Details

The descriptive details of this passage include:

Sounds: The whirlwinds (v. 1); the people's sighing (v. 2); the screaming of child birth (v. 3); the hooves of the animals (vv. 7, 9); the voice of the Lord (v. 6); the voice of the watcher (vv. 8-10);

Sights: Dust stirred up by the whirlwinds (v. 1); table, rugs, and military shields (v. 5); the animals (vv. 7, 9); the watcher and the watchtower (vv. 6-10); the day and the night (v. 8); the riders (v. 7, 9); and the broken images of Babylon's gods (v. 9). Preachers might imaginatively assign colors to each of these sights. For example, the horses in v. 7 might be "jet black stallions.";

Smells: Food and drink on the table that the army consumes prior to battle (v. 5);

Tastes: Food and drink (v. 5);

Textures: The rugs upon which the solders sit as they eat the meal (v. 5).

Notes

- For further information, consult Hope Franklin, John. The Emancipation Proclamation. (1963) Garden City, NY: Doubleday; reprint edition, IL: Harlan Davidson, 1995.

|