HOMECOMING

(Family and Friends Day)

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Sunday, September 21, 2008

Ralph Wheeler, Guest Lectionary Cultural Resource Commentator

Attorney and long-time civil rights activist, Oakland, CA

I. Definitions and Historical Background

What and Where is Home?

African American church Homecomings stem from the root word “home.” In our community, the word “home” means more than a physical place. It is more than a plot of land, house, city, state, nation, or continent. It is also more than a family, clan, tribe, or church. It is all of that; but it is also much more.

For African Americans, home is a continuum of experiences--a celebration of memories, stream of interactions, and a cacophony of feelings. It is a line of broken and unbroken relationships, and a circle of life filled with trials, tribulations and hallelujah moments. It is even more; home for us is a symphony of beliefs--a visible and invisible chain of human history that is imprinted on the DNA of each black congregant. And, yes, home is a human library of black hopes, dreams, disappointments, failures, successes, and achievements--personal and public. It is an ancestral map of lost tribes, muted tongues, forgotten civilizations, discarded gods, and transformed lives. It is built, brick-by-brick, by each congregant, family and community. Home, for all African Americans, is both a fixed and portable concept. However, every now and then, we have to go back to the old landmark, to that fixed place and commune together.

The Homeward Call

So, when an African American church sends its clarion call to its current and former membership and its web of friends, to join it in its Homecoming celebration, it is an invitation steeped in place and time, history and tradition, and culture and faith. That call rivals the call of the African drum that our ancestors answered centuries ago. Each congregant knows its importance and heeds its call. It was out of this landscape that the liturgical moment of Homecoming was born in the African American church.

A Celebration of Culture

Homecoming is celebrated differently in different churches by different denominations. Some congregations celebrate it for a day, while others celebrate it for a full week. Many black churches combine their Homecoming celebration with their church anniversary. The service is always rooted in black culture, faith, history and thanksgiving.

The Homecoming service is one of the best attended services on the church calendar. It is a service to which families, friends and former church members flock from everywhere. And, usually, every age group of the church is celebrated, with particular attention given to inclusion of the church’s children and young adults in the Homecoming program.

The service is usually culturally rich -- in that it may include various art forms, including various musical forms (e.g., Spirituals, Hymns, Gospels, Jazz, Blues, Classical, etc.), dance, films, plays, poetry, and seminars and lectures. The traditional sermon is often replaced by a message from a nationally known or a locally gifted speaker. The service often includes or ends with a congregational meal of traditional African and African American foods.

Recalling the Landmarks

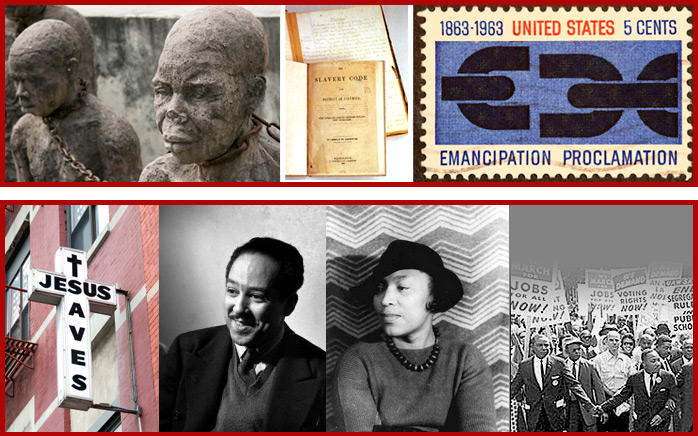

To fully appreciate the African American church Homecoming experience, one must recall some of the historical landmarks that resulted in its creation and growth:

• the African slave trade;1

• the middle passage;2

• plantation life; 3

• free blacks in the antebellum south and other states;4

• the black church as an “invisible institution;”

• the “institutional black church;”5

• the Declaration of Independence;6

• the Emancipation Proclamation;7

• the Reconstruction Era;8

• the Black Codes;9

• the early black schools and colleges;10

• the Great Depression;11

• the Harlem Renaissance;12

• Brown v. Board of Education;13

• the Jim and Jane Crow laws;14

• the Civil Rights Movement;15

• the March on Washington;16 and

• the Civil Rights Act of 1964.17

|

Each of these landmarks, from the slave barracoons of Africa to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, had a direct, or indirect, role in the birth and growth of the African American church Homecoming ritual. As such, the African American church Homecoming ritual is a quintessential African and African American experience.

II. Memories and Traditions

Although I have been a member of two large, urban African American churches (Third Baptist Church of San Francisco, CA and Allen Temple Baptist Church of Oakland, CA), my favorite and most treasured memories of Homecoming go back to the small, rural church of my childhood -- the Holy Ghost Missionary Baptist Church of Clinton, Mississippi. It was there that I attended my first church Homecoming.

I vividly remember those services. They were almost always held during the summer when the weather was good. It also was a time when out-of-state relatives were able to travel back “home.” They came driving their long, shiny cars. They came wearing their fancy urban clothes, and sporting their new Stetson hats. They came speaking with new accents and strange tongues, and talking about how great it was to be living up north. But it was all good, because we were all gathering for Homecoming, and, on that day, everybody put their best foot forward.

Songs for the Heart and Soul

Homecoming was the one day the elders of our church allowed non-religious art forms to intrude into the church’s sacred worship services. On Homecoming day, it was not unusual for some young person with a voice like Paul Robinson or Leonytene Price to raise the roof by singing a great classical or spiritual number that reflected the passions, travails, and triumphs of black America; or, for some young, gifted musician to play Billie Holiday’s “God Bless the Child.”18 Standing ovations and shouts of hallelujah were the Church’s normal responses. We, even the young, knew the deep and double meanings of these songs.

We were taken to even higher levels by the choirs. On Homecoming day, the choir stand was always full. Sometimes, former choir members came back and rejoined the choir that day. They sang familiar songs, always an “A” and “B” selection. “Precious Memories,”19 and “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms”20 were crowd favorites. These were more than songs of remembrance. They were songs of survival, hope and promise. They were songs for the heart and soul.

The choirs petitioned heaven with such earnestness, fervor and musical perfection that the pastor or mistress/master of ceremonies would spontaneously call out the names of some of the church’s deceased members and remark: “I know they are leaning over the balconies of heaven, rejoicing in this great day.”

The entire church clapped, moved and swayed in unison as the choir rocked with perfection. We knew every word of every song, and we sang along with the choir--hundreds of black Mississippi voices on one accord, praising God, celebrating our culture, and affirming each other. Even the ushers played their roll, providing fans, smelling salts and comforting those who were over taken by the Holy Spirit.

On this day, we didn’t focus on the horrible murder of Emmett Till, or on any of the other demeaning or oppressive acts we encountered daily. It didn’t matter that our home state was the meanest and poorest state in the American union--no, not that day. This was a day of celebration. I’m talking about an old-fashioned Mississippi Homecoming. It was better than the State fair.

Poetry from the Community

On the poetic side, my grandmother, Mrs. Ezell Holly Wheeler, and Mrs. Everette Rose, who were famous for their poetic recitations, would recite one of their own ditties or one of Langston Hughes’s or some other poet’s works. The poems they chose for Homecoming were always filled with humor or biting wit. Like the following poem, their recitations reflected aspects of life that were familiar to the congregation:

Eighty-nine years ago, God took a small lump

of clay and fashioned a spirit of female. He blew

into her nostrils and she became a breathing,

living soul.

He colored her sweet. He

colored her gentle. He

colored her Eva Benson Crisler. A bouncing

baby girl she was. She wasn’t just born. She

strutted into this world, making music of her

own.

When she walked by little boys would die and

little girls would squeal, just listening to Aunt

Eva’s heels. Clickety clack, clack, clack.

Clickety clack, clack, clack.

The sound of her walk would knock you dead.

Her steps were quick, short and smooth. She

moved to a silent, inward beat, not even

restrained by the Mississippi heat.

I remember those Saturday afternoons. You

know, when fun was clean and Farish Street was

only a wee bit mean--a place where families

gathered to shop for the

coming weeks; and, the

Blackstone Café was a place of retreat.

Cheese was still a dime and a dollar would buy

a whole lot of time. The street was full of life

and packed from side to side. Peanuts were

roasted. Fish were fried. Hair was done. And,

money was spent that hadn't been earned. It was

Summer time in Jackson, Mississippi.

Aunt Eva and Uncle Bob would ease into town.

She in her fancy silk dress, and he in his Stetson

Brown. Heads would turn and lips would

whisper, “Eva and Bob are here!”

Aunt Eva would glide into her strut. Men’s hats

would tip, giving subtle hints of respect.

Women would stare with jealous rage, but this

was not their stage.

Aunt Eva never gave them the time of day-not

even her perfume would linger their way. Her

hips moved with a syncopated beat-not a speck

of dust dared touch her feet. As she strutted her

stuff, the music from the Blackstone would

catch her ear. Then, she would move into a

switch that brought the house down. It was

Saturday night and Bob and Eva were in town.21 |

Biscuits, Gospel and Blues

After standing in long lines to honor our favorite cooks and filling our stomachs with the best fried chicken, meatloaf, butter beans with okra, potato salad, fluffy biscuits, lemon cake, sweet potato pie on earth, we readied ourselves for the afternoon gospel musical. It was the highlight of the Homecoming experience.

The singing groups and male quartets put on a show that could have been taken directly to New York’s Apollo Theater. Their stylish outfits, smooth choreography, and amplified bass guitars took most of us as close as we ever expected to get to a James Brown, Temptations or Smokey Robinson and the Miracles show. And it was all happening at our little church in Clinton, Mississippi--right in front of the pastor, deacons and the mothers of the church. Was this heaven or what?

Each Homecoming day ended on this high note. It made it so much easier to say good-bye to our friends and out-of-state family members. We parted company holding great expectations of “same time next year.” On Sunday morning, however, we would go back to our old piano, Doctor Watts’ hymns, and regular order of service.

III. Landmark Preservations

As we negotiate this new century that is steeped in technology, each congregation has a golden opportunity to systematically document its history. The Homecoming liturgical moment can become the vehicle to achieve that end.

Two possible projects are: (1) use of Federal preservation laws and related state and local historic preservation statutes to landmark our churches and their history; and, (2) creation of an on-site church library to house important church documents. Please talk to local museum curators and/or librarians to learn how best to establish a library to store important documents.

All church departments should be encouraged to incorporate aspects of these projects into their program activities. Students should be encouraged to use the church’s library as a primary source for their secular school activities. Implementation of these projects will ensure there are orderly ways to systematically record and maintain the traditions, history and contributions of the black church to its congregation and community.

If local churches do not have the in-house talent to plan and implement these projects, they should consider partnering with neighboring schools, colleges, and seminaries, and local historic preservation groups. In addition, they should consider seeking foundation support to assist with the financial side of these missions.

IV. Possible Homecoming Program Activities

a. Candle-light service for all deceased pastors and members;

b. Church history exhibit of important documents;

c. Video presentation of the church's history;

d. Drumming ceremony; and

e. Guided tour of important local African American landmarks, including the cemetery most associated with the church. |

V. Songs for This Moment

I have so many favorite songs that I remember singing during Homecoming celebrations. Two that come to mind are “Walk Together Children” and “This Little Light of Mine.” “Walk Together Children” was sung, not so much for its actual lyrics, but for its coded messages that encouraged us to “not get weary,” to stay united, and to believe that, in the end, right would win although segregation still held sway. The second song was chosen because it was a song of determination regarding our commitment to live as Christians in the world. It was also chosen because it was so well known and had a tempo that always roused the congregation.

Walk Together Children

Walk together children, don’t you get weary,

walk together children, don’t you get weary,

walk together children, don’t you get weary,

there’s a great camp meeting in the promised land.

We’re gonna walk and never tire,

walk and never tire, there’s a

great camp meeting n the promised land.

22

This Little Light of Mine

This little light of mine, I’m gonna let it shine.

This little light of mine, I’m gonna let it shine.

This little light of mine, I’m gonna let it shine.

Let it shine, let it shine, let it shine.

Verse two

Everywhere I go, I’m gonna let it shine

Everywhere I go, I’m gonna let it shine

Everywhere I go, I’m gonna let it shine

Let it shine, let it shine, let it shine.

Verse three

Jesus gave it to me, I’m gonna let it shine.

Jesus gave it to me, I’m gonna let it shine.

Jesus gave it to me, I’m gonna let it shine.

Let it shine, let it shine, let it shine.

Verse 4

Shine, shine, shine, I’m gonna let it shine….

Verse 5

All in my home, I’m gonna let it shine….23

1. Hughes, Langston, Milton Meltzer and C. Eric Lincoln. A Pictorial History of the Negro in America. New York: Crown Publishers, 1968. pp. 8-10

2. Franklin, John Hope, and Alfred A. Moss. From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994. pp. 44-45

3. Ibid. pp. 143-148

4. Ibid. pp. 167-191

5. Frazier, Edward Franklin, and C. Eric Lincoln. The Negro Church in America. Sourcebooks in Negro History. New York: Schocken Books, 1974. pp. 20-46

6. Franklin and Moss. Pp. 82-83

7. Franklin and Moss. Pp. 686-687

8. Franklin and Moss. Pp. 245-271

9. Hughes, Langston, Milton Meltzer and C. Eric Lincoln. A Pictorial History of the Negro in America. Pp. 197-198; Franklin, John Hope, and Alfred A. Moss. From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans. Pp. 250-251

10. Franklin and Moss. Pp. 112-113,155-156,171-178, 224-225, and 448-452

11. Franklin and Moss. Pp. 419-422

12. Franklin and Moss. Pp. 400-417

13. “Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954).” Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Brown_v._Board_of_Education&oldid=230597059. Accessed 9 May 2008.

14. Franklin and Moss. Pp. 290-291

15. Carson, Clayborne. Civil Rights Chronicle: The African-American Struggle for Freedom. Lincolnwood, Ill: Legacy, 2003. pp. 170-347

16. Franklin and Moss. Pp. 535-537

17. Franklin and Moss. Pp. 538-539

18. Holiday, Billie, Arthur Herzog, and Jerry Pinkney. God Bless the Child. New York, NY: HarperCollins/Amistad, 2004.

19. African American Heritage Hymnal. Chicago IL: GIA Publications, 2001. #517

20. Ibid. #371

21. Poem written by Ralph Wheeler. Unpublished, © 1994.

22. African American Heritage Hymnal. #541

23. African American Heritage Hymnal. #549