ECUMENICAL DAY OF WORSHIP

CULTURAL RESOURCES

ECUMENICAL DAY OF WORSHIP

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Sunday, September 7, 2008

Bernice Johnson Reagon, Cultural Resources Commentator

I. Introduction

The scripture for this lectionary moment, Psalm 133: 1-3, calls for unity, a oneness in God. Contemporary expressions of unity in the form of ecumenism

take place within congregations, across denominations and faith communities. The text of a spiritual beckons us to unity; it calls us to come and go

to that land where we’ll all be united:

Come and go with me to that land, come and go with me to that land

Come and go with me to that land, where I’m bound, where I’m bound

Come and go with me to that land, come and go with me to that land

Come and go with me to that land, where I’m bound

Nothing but peace in that land…1

This African American spiritual describes a number of conditions and goals. The singer is journeying,

moving from where she is to a better place. Although the word “land” is used to name the place, conditions conveying the nature of the

place are described in each cycle of the song. This song can go on for a long time. As a child, I was sure it must be heaven that we

were being called to consider – no pain, no sickness, nothing but joy, no more hatred. With this moment on our lectionary calendar,

we are called to understand that journeying toward that land requires us to actually engage in the courageous work of creating that

which we all seek – the unity of humanity. So much of what is destructive in our society is created by concepts of differences that

not only separate, but also seem to provide increased opportunities to name “the other” as the source of all problems. This not only

creates problems for the group that is perceived as different, but it keeps the holder of the perception from turning the light onto

her and his own contributions to the problems.

No more hatred in that land, no more hatred in that land

No more hatred in that land where I’m bound…

II. Definitional Notes on the Concept of Pluralism

Harvard professor Diana Eck’s work has centered on the increasing complexity of the United States of America’s

population, and the importance of fluency in the complex of belief systems that accompany that increase. Rather

than a broad call for unity, Eck lays out incremental processes that allow people to come together across

differences to explore the ways to focus on what is shared and can be a foundation for decreasing distance,

animosity, and hostility. Since 1991, she has headed the Pluralism Project. While it is a long way from

the call to oneness in the scripture assigned to this lectionary moment, Dr. Eck offers suggestions to those

of us who are beginning to search for ways to fashion an ecumenical experience for our worship communities. It is important to

note that Eck’s work is centered on the complexity and layered reality of the demographic and cultural makeup of the nation:

and the crucial importance of increased fluency in not just proclamations of unity and ecumenical efforts, but the necessity

of building a proficiency in methods of coming together in equity and respect across varied communities sharing the same space.

She begins by distinguishing pluralism from diversity:

First, pluralism is not diversity alone, but the energetic engagement with diversity. Diversity can and has meant

the creation of religious ghettoes with little traffic between or among them. Today, religious diversity is a given, but pluralism

is not a given; it is an achievement. Mere diversity without real encounter and relationship will yield increasing tensions in our societies.2

We’ll all be together in that land, we’ll all be together in that land

We’ll all be together in that land, where I’m bound, where I’m bound…

II. A Remembrance of an Ecumenical Service by Reverend Brad R. Braxton

When I was Senior Pastor of Douglas Memorial Community Church in Baltimore, we participated in a symposium with the Beth El Congregation, one of the

synagogues in Baltimore. The event was a marvelous interfaith gathering in a city that has sizeable African American and Jewish communities.

The symposium was sponsored by the Institute for Christian and Jewish Studies (ICJS) in Baltimore. The ICJS continues to facilitate interfaith

dialogue in Baltimore and beyond.3

The symposium was part of a larger interfaith initiative where parishioners and clergy from African American, white Christian congregations,

and Jewish congregations met together regularly to read and discuss the scripture they share – the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. These dialogues

concerning scripture and our various religious and cultural traditions enhanced ecumenical awareness among participants.

The symposium involving Douglas Memorial Community Church and Beth El Congregation was a memorable moment of teaching and sharing.

The event was entitled “Hope and Resistance among Jews and African American Christians: The Message and the Music of our Religious Communities.”

Approximately 600 people, reflecting the religious and cultural diversity of Baltimore, attended the event.

During the symposium, Rabbi Mark Loeb and I lectured on the role of religion and music in the genocides that our respective ancestors

experienced (i.e., the Jewish Holocaust and Trans-Atlantic slavery). Our lectures focused on the role of apocalyptic thought in

scripture, and in the historic experiences of our respective communities. Apocalyptic (from a Greek word meaning “revelation”)

suggests that God’s ultimate plans for the world are undetectable to people and can only be known through divine revelation.

This revelation is often given to an individual or group, by means of angelic messengers or spectacular images and visions.

My lecture examined how apocalyptic thought often establishes two levels of reality. The lower level of reality is where persons

strive to be faithful witnesses to God amid intense suffering. The upper level is where God has conquered evil. Thus, justice and

peace reign supreme in the upper level.

Apocalyptic thought was a key feature of African American hope and resistance during slavery. While slaves were suffering intense

persecution in the lower realm of existence on plantations, they believed that God was still operative in the upper realm of existence.

Hence, they sang lyrics like, “Over my head, I hear music in the air…there must be a God somewhere.” The sorrow of slavery could not

drown out the praise music those slaves imaginatively heard in the upper realm of existence. The Douglas Church Inspirational Choir,

in keeping with the theme of the symposium that evening, sang spirituals such as: “Ride on King Jesus;” “I Want to be Ready to Walk

in Jerusalem Just Like John;” and “I Am Seeking for a City” – songs that reflect the robust apocalyptic imagination of African Americans.

Rabbi Loeb talked about how apocalyptic thought affirmed and sustained the humanity of Jews in the face of the gross inhumanity of

the Jewish Holocaust – from forced marches to starvation, to the gas chambers in concentration camps. As an example of apocalyptic

hope, the Beth El cantor sang Psalm 126, a Song of Ascent. This Psalm might have been sung as worshippers in ancient Israel ascended

the mountain on their way to the Temple for one of the great Jewish festivals.

A central part of Psalm 126 is verse 5: “May those who sow in tears reap with shouts of joy.” Rabbi Loeb pointed out that the

fifteen Songs of Ascent in scripture (Psalms 120 -134) may have corresponded to the fifteen steps leading from the outer court

to the inner court of the Temple. Thus, as twentieth century Jews were oppressed and brutalized in concentrations camps, they

would sing ancient songs about the Temple, revealing their steadfast devotion to the images and institutions that made them who

they are as a religious people.

III. Organized Ecumenical Movements

A. The World Missionary Conference

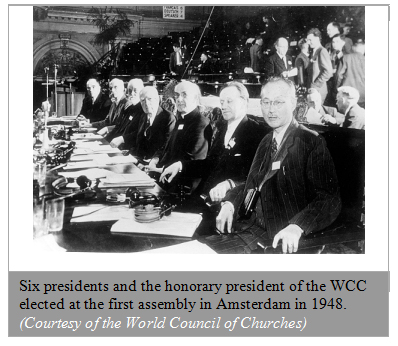

The origins of the modern ecumenical movement began with the World Missionary Conference of 1910 in Edinburgh, Scotland. Chaired

by the American Methodist layman John R. Mott, the conference included more than 1,200 representatives from Protestant denominations

around the world – Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches remained absent. This meeting led to the founding of several ecumenical

projects and agencies: the International Missionary Council in 1921, which united the network of national and regional councils that

were formed after 1910; the Faith and Order Movement in Lausanne France in 1927; the World Council of Churches in 1948; and the National

Council of Churches of the USA in 1950.4

The First World War slowed the ecumenical movement, but it was revived after World War II. Thrown together

in response to Hitler’s atrocities, and sometimes sharing prison cells, Catholics and Protestants found that

their common faith in Jesus Christ and the sacred text of the Bible transcended the history that divided them.

Some of the early leaders of the World Council of Churches had spent the war years smuggling Jews to safety.

In the United States, the ecumenical vision played an important role in the Civil Rights Movement.5

B. The National Council of Churches of the USA

Formed in 1950, the National Council of Churches (NCC) is an alliance of 35 Protestant, Anglican, Orthodox, and historic African American

member communions - totaling over 100,000 congregations and 45 million congregants.

Statement of Faith

The National Council of Churches is a community of Christian communions, which, in response to the gospel as revealed

in the Scriptures, confess Jesus Christ, the incarnate Word of God, as Savior and Lord. These communions covenant with

one another to manifest ever more fully the unity of the Church. Relying upon the transforming power of the Holy Spirit,

the communions come together as the Council in common mission, serving in all creation to the glory of God.6

--from the Preamble to the NCC Constitution

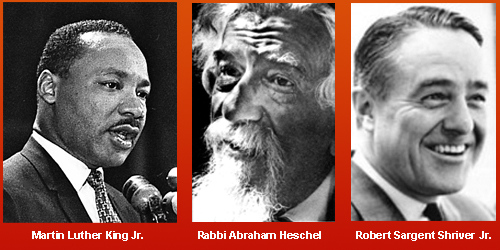

C. 1963 Chicago Conference on Religion and Race7

From January 14-17, 1963, in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation and hosted

by Albert Cardinal Meyer of Chicago, more than 1,000 delegates gathered in Chicago in a historic ecumenical National

Conference on Religion and Race. Theologian Rabbi Abraham J. Heschel, in his opening speech “Religion and Race,”

wondered if the two words could actually ever be connected in the way they appeared as the theme of the gathering:

“How can the two be uttered together? To act in the spirit of religion is to unite that which lies apart, to remember

that humanity as a whole is God’s beloved child. To act in the spirit of race is to sunder, to slash, to dismember

the flesh of living humanity…. Perhaps this conference should have been called ‘Religion or Race.’” Heschel further

stated that that the soul of Judaism was at stake. He paralleled the issues of this conference with the first

conference on race between Moses and Pharaoh. “It was easier for the children of Israel to cross the Red Sea

than for a Negro to cross certain university campuses.”

Robert Sargent Shriver, Jr., then director of the Peace Corps, wondered aloud to his gathered colleagues,

“…why can I go to church 52 times a year and not hear one sermon on the practical problems of race relations?”

On January 16, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke before the conference. Fresh from a commitment to have his

organization continue their work by confronting racism in an organized direct action campaign in Birmingham,

Alabama, he reminded the group again that racism was in the south, but that the organized church created the most

segregated hour in the nation. “Eleven o’clock on Sunday morning is still America’s most segregated hour, and

the Sunday school is still the most segregated school of the week . . . We have listened to the eloquent words

flowing from the lips of Christian and Jewish statesmen. Will this conference end up like all too many conferences on race . . .

One must not only preach with his voice, he must preach it with his life.” Both Rev. King and Rabbi Heschel agreed on the cry

of Prophet Amos: “Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.” Neither man, in stressing the need

for prophecy, was talking about “foretelling,” Rather, they were talking about what Heschel described as “the voice that God has lent to the silent agony,”

contemporary prophetic witnesses, offering themselves as ready, willing, and able to take on the evil and poison of racism

at its core. This strategy of absorbing directly whatever the evil of racism had to offer had already been demonstrated by

students in sit-ins, and by the Freedom Riders; now the call was to a collective human religious witness on the frontline,

in the places where the struggle was being waged.

The conference closed with a call, “An Appeal to the Conscience of the American People.”

“We call upon all the American people to work, to pray and to act courageously in the cause of human equality and dignity while there

is still time, to eliminate racism permanently and decisively, to seize the historic opportunity the Lord has given us for healing an

ancient rupture

in the human family, to do this for the glory of God.” 8

We’ll all be together in that land, we’ll all be together in that land

We’ll all be together in that land, where I’m bound…

D. Apartheid and the Kairos Document9

On July 21, 1985, the South African apartheid government issued a national state of emergency that gave them

expanded powers to act against those organized against the apartheid state. In response, an ecumenical group of

theologians, pastors, and church leaders gathered in Soweto, and after a series of meetings offered The Kairos

Document in opposition to these policies in September 1985. The document was signed by 150 leaders representing more than

20 religious denominations; however, the names were not made public. The Kairos Document did not represent all

South African Christians; in fact, it includes a serious critique of certain aspects of organized South African Churches.

It does represent itself as the Church and, the document spoke not only to the contemporary crisis, but also provided a

historical perspective from which to look at, and critique, the South African government’s policies and the churches that

supported, or tried to stand neutral, in the face of those policies.

The word “kairos” comes from the New Testament Greek, and is a concept that evokes a moment of grace and opportunity in which God issues

a challenge to decisive action. Kairos does not imply chronological time (kronos), so much as a moment of truth, a period when the

mundane reaches to the sacred nature of man. A Kairos theology would hold that there can be no compromise or reconciliation with evil;

apartheid was evil. Since the issuance of the original versions of the document, there have been revised versions and there have also been a

number of Kairos documents in other areas of the world calling on the church to be a voice within society speaking out against evil

and exploitation.

The Preface lays out the process and makes clear the challenge to the church:

The Kairos document is a Christian, biblical and theological comment on the political crisis in South Africa today. It is an attempt

by concerned Christians in South Africa to reflect on the situation of death in our country. It is a critique of the current theological

models that determine the type of activities the Church engages in to try to resolve the problems of the country. It is an attempt to

develop, out of this perplexing situation, an alternative biblical and theological model that will in turn lead to forms of activity

that will make a real difference to the future of our country….

25 September 1985 Johannesburg

E. The Attacks of September 11, 2001

On September 14, 2001, three days after airplanes turned into bombs ploughed into the World Trade Centers, the Pentagon, and a third

plane failing to reach its target, fell into a Pennsylvania field, the National Council of Churches entered the dialogue in an ecumenical

voice with a statement by religious leaders across denominations and faith communities.

More Than 200 Have Now Signed Interfaith “Response to Terrorism”

September 14, 2001 – Now numbering more than 200, a broad spectrum of the U.S. religious community, including Evangelical, Roman Catholic, Orthodox

and Protestant Christians – as well as Muslim and Jewish leaders, have joined their signatures to the interfaith statement “Deny Them

Their Victory:

A Religious Response to Terrorism.” The breadth of participation has made the document one of the most inclusive religious statements ever released.

Signers, who gave their personal endorsement, included the heads of denominations, national and regional religious organizations, and parachurch groups,

local pastors and rabbis, and theologians and professors from all parts of the nation.10 More than 100 responded within the first 24 hours.

By Friday,

September 14, more than 200 had signed.

Deny Them Their Victory: A Religious Response to Terrorism11

“We, American religious leaders, share the broken hearts of our fellow citizens. The worst terrorist attack in history that assaulted New York City,

Washington, D.C., and Pennsylvania, has been felt in every American community. Each life lost was of unique and sacred value in the eyes of God, and

the connections Americans feel to those lives run very deep. In the face of such a cruel catastrophe, it is a time to look to God and to each other

for the strength we need and the response we will make. We must dig deep to the roots of our faith for sustenance, solace, and wisdom.

First, we must find a word of consolation for the untold pain and suffering of our people. Our congregations will offer their practical and

pastoral resources to bind up the wounds of the nation. We can become safe places to weep and secure places to begin rebuilding our shattered lives

and communities. Our houses of worship should become public arenas for common prayer, community discussion, eventual healing, and forgiveness.

Second, we offer a word of sober restraint as our nation discerns what its response will be. We share the deep anger toward those who so

callously and massively destroy innocent lives, no matter what the grievances or injustices invoked. In the name of God, we too demand that those

responsible for these utterly evil acts be found and brought to justice. Those culpable must not escape accountability. But we must not, out of

anger and vengeance, indiscriminately retaliate in ways that bring on even more loss of innocent life. We pray that President Bush and members

of Congress will seek the wisdom of God as they

decide upon the appropriate response.

Third, we face deep and profound questions of what this attack on America will do to us as a nation. The terrorists have offered

us a stark view of the world they would create, where the remedy to every human grievance and injustice is a resort to the random and

cowardly violence of revenge - even against the most innocent. Having taken thousands of our lives, attacked our national symbols,

forced our political leaders to flee their chambers of governance, disrupted our work and families, and struck fear into the hearts

of our children, the terrorists must feel victorious.

But we can deny them their victory by refusing to submit to a world created in their image. Terrorism inflicts not only death and

destruction but also emotional oppression to further its aims. We must not allow this terror to drive us away from being the people

God has called us to be. We assert the vision of community, tolerance, compassion, justice, and the sacredness of human life, which

lies at the heart of all our religious traditions. America must be a safe place for all our citizens in all their diversity. It is

especially important that our citizens who share national origins, ethnicity, or religion with whoever attacked us are, themselves,

protected among us.

Our American illusion of invulnerability has been shattered. From now on, we will look at the world in a different way, and this attack

on our life as a nation will become a test of our national character. Let us make the right choices in this crisis - to pray, act, and

unite against the bitter fruits of division, hatred, and violence. Let us rededicate ourselves to global peace, human dignity, and the

eradication of injustice that breeds rage and vengeance.

As we gather in our houses of worship, let us begin a process of seeking the healing and grace of God.”

No more hatred in that land, no more hatred in that land

No more hatred in that land, where I’m bound, where I’m bound…

There’s nothing to fear in that land, nothing to fear in that land

There’s nothing to fear in that land, where I’m bound…

Come and go to that land, come and go to that land

Come and go to that land where I’m bound…

Notes

-

Come and Go With Me. African American Spiritual

- address “What is Pluralism?” The Pluralism Project, Harvard University. 1531 Cambridge St. Cambridge, MA 02139 email staff@pluralism.org,

http://pluralism.org/pages/pluralism/what_is_pluralism accessed 5 May 2008

- Institute for Christian and Jewish Studies. The Institute for Christian & Jewish Studies 956 Dulaney Valley Road, Baltimore, MD 21204. 410.494.7161 / fax: 410.494.7169 www.icjs.org accessed 5 May 2008

- Tippett, Krista. “History of the Ecumenical Movement.” Speaking of Faith/American Public Media. http://speakingoffaith.publicradio.org/programs/livingreconciliation/particulars.shtml

- Ibid.

- National Council of Churches, 475 Riverside Drive, 8th floor, New York, NY 10115. http://www.nccusa.org/about/about_ncc.htm accessed 5 May 2008

- The Martin Luther King Research and Education Institute http://www.stanford.edu/group/king/ --At site enter in search box “National conference on race and religion” for article titled “King Encyclopedia:National Conference on Race and Religion”

- Ibid.

- "Kairos Document." Wikipedia. 1 Apr 2008 Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Kairos_Document&oldid=202492718 accessed 5 May 2008

- “Deny Them Their Victory: A Religious Response to Terrorism.” National Conference of Churches. http://www.ncccusa.org/ accessed 5 May 2008

- Ibid.

|