|

MISSION SUNDAY (MISSION WORK ABROAD)

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Sunday, May 5, 2013

Lois Edmonds, Guest Cultural Resource Commentator

Retired school teacher and women and civil rights activist, San Francisco, CA

I. Introduction

The well-known story of Jesus feeding the multitude with a few fish and bread (Mark 6:34-44) is a perfect example of how mission work can move from crowds to be helped to communities that we help to help themselves. In part, because of the success of their own outreach, the disciples and Jesus are followed by a crowd. The disciples, no doubt fatigued from work, suggest that the crowd be “sent away.” Jesus tells them to “give the people something to eat.” However, as the story shows, the resources will not come from the disciples alone. Jesus tells them to assess the resources of the people; Jesus knows that what the people have is enough. The disciples assume that the hungry crowd is helpless and must either be dispersed with their needs ignored or become dependent on the social service of the disciples. Jesus teaches them instead how to organize the crowd into a community and how to look more deeply to discover the abundant resources already present—resources the crowd itself may not have known existed. Then Jesus directs them to have the crowd sit down in groups—not just any size groups, but groups of fifty and one hundred. In that moment, the crowd becomes a community. Then, to reinforce their role as leaders, after blessing and breaking the loaves and the fish, Jesus gives the food to the disciples to set before the people. It is they and the people, not Jesus, who are to do the feeding.

Without diminishing the miracle, notice how fundamentally this move of having the disciples work with the crowd so that all are fed alters the dynamic of the narrative. You can visualize the significance of the transformation. I picture a supply truck arriving in a refugee camp, with the hungry crowd gathering as a frenzied pack to get their share of the scarce resources before they quickly disappear. In community, the dynamics are altogether different. Sitting in a circle, you connect with those around you. As you pass the bread from person to person, aware of how many people it has to feed, you are less likely to take more than your share, both because you can see the faces of those around you and because the collective will of the group would not allow anything else. It is now time that we do mission work that brings resources to people while showing them the resources they have when they work together as a community.

II. Key Words: Missions, Community, Capacity Building

Every African American Lectionary unit is framed by key words. In the case of today’s unit, the key words established by the Lectionary team were: missions, community, and capacity building. All three words aptly describe the aims of mission work that is done abroad. First, it must be mission-focused. The definition of what it means to do mission work abroad, also known as world missions, has changed over time by most groups who do mission work outside of the United States. The study of world missions is replete with a history of mission workers, mainly white, and sometimes African American, who took their messages into other countries, such as Africa, with the aim of indoctrinating their brothers and sisters against their traditional religions, community mores, and beliefs. They wanted to make them cultural citizens of America and its religions and community mores. In the not-too-distant past, persons to whom mission outreach was intended were seen as “pitiful others” in need of salvation from outsiders. Mission workers went into countries and instead of partnering with the residents of these countries, plundered and indoctrinated all the while acting with the certainty that God was on their side. Here, the words of Abraham Lincoln are apt: Our greatest concern should be “whether we are on God’s side.”

Thank goodness many, though not all, have seen the harm in such approaches. Having completed six mission trips in my life, I have learned a great deal over time. One of the main things that I have learned is that mission work, when mission-focused, is not first about propagating a religion, not even Christianity. It is about seeing the suffering as partnering pilgrims on earth who are our brothers and sisters who need us and we need them. Most can quickly recite the reasons why persons in suffering countries need us. Let me state two reasons why we need them. First, we need them because all people of the earth are inextricably bound by our Creator for all times and in all places. In God’s eyes, there are no premiere nations and third world countries. We are all just developing nations trying to determine how to live together peacefully and ethically; on most days, regardless of the nation in which we are locate we fail at both. Second, we need our brothers and sisters around the world because they help keep us focused on being better—better at giving, better at sacrificing, better at forgiving, better at not majoring in minors, better at being peacemakers, and better at living like the sacrificing savior whom we who are Christians claim as our main model.

Second, mission work abroad must be about community: sustaining community, uplifting the notion of community at all times, and living as members of a world community. This also encompasses our third key word: capacity building. Too quickly do those of us in America forget that once upon a time, in 1607 to be exact, people from England arrived in North America and claimed the first English settlement in Jamestown, Virginia. They came seeking a community in which they could be free to live out their lives as they wished, as did those who followed them. Although Americans take great pride in their fight to be a community of free people; we quickly forget that we took this right away from native North Americans who were here when the first visitors to North America arrived, and we denied it altogether to blacks whom white North Americans enslaved. Remember, one of the main ideas used to ravage Africa and to wipe out Native Americans was that they were both savages or heathens. It was said by many a scholar and preacher that we were saving the souls of blacks even as we snatched them from their homeland and brought them shackled to America. This “crusading tendency” of American mission workers continues even today. But that is not how communities are built.

After many years of work in Africa, Latin America, and other countries racked by poverty, war, and the plundering of their people and natural resources by other countries, mission agencies and development agencies and mission workers are starting to look anew at whether their efforts to help those in need have done more harm than good. In other words, one of the main questions now being asked is have decades of mission efforts done more to tear down communities than to build the capacity of communities/countries? David Sogge writes in a Christian Century article, “In the 1980s books appeared with titles such as Giving Is Taking, Deadly Help and Lords of Poverty…In the late 90s [there were books with titles such as] The Road to Hell: The Ravaging Effects of Foreign Aid and International Charity; Famine Crimes: Politics and the Disaster Relief Industry in Africa; and Aiding Violence: The Development Enterprise in Rwanda.”1

In the same article Sogge analyzes the book Future Positive: International Co-operation in the 21st Century by Michael Edwards. Edwards, now at the Ford Foundation, has worked for the World Bank and has a wide breath of experience with non-governmental development organizations, which we know better as aide organizations, although the two (aide and development) may not both be aims of those who do world mission work. Sogge writes:

His [Edward’s] argument for “building constituencies for change” is a plea to move beyond the intervention mode that passes for “international cooperation, beyond the patronizing practices of private aid agencies driven by business competition rather than by civil constituencies and emancipatory agendas shared with others. Genuine cooperation across boundaries is possible and necessary. To continue with aid as we know it is to risk diminishing both sides, turning one group into philanthropists and the other into supplicants…”

Edward concludes: “True freedom is attainable only through relations with others, since in an interconnected world I can never be safe until you are secure; nor can one person be whole unless others are fulfilled. That is only possible in a cooperative world. Is that the kind of world we want to live in and bequeath to those we love. If so, our responsibilities are clear.”2

The issue of how the capacity of suffering countries can be increased is complex and has and will come to the fore more and more as those countries and development entities (NGOs,3 the World Bank, and the European Union) who are wealthy enough to provide aide, quake under the shadow of harsh austerity measures and financial deficits in their own backyards. Hopefully, churches and other religious groups who do mission work abroad will become more involved in shaping this discussion. The Church and those who do mission work abroad cannot leave it to entities such as the World Bank, the European Union, or the American government, each of whom are ultimately looking out for their own interests, to make capacity building decisions for poor countries and continents, especially the continents of Africa and Latin America.

III. The Lott Carey Foreign Mission Convention

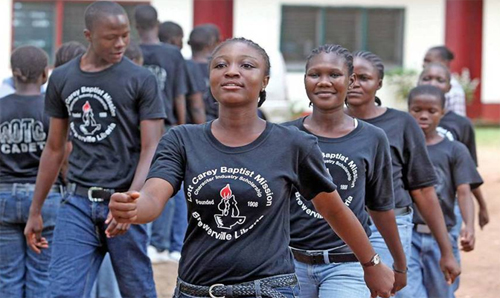

The Lott Carey Foreign Mission Convention, a mission organization led by African Americans and organized in 1897, is an exemplar of an organization that is mission-focused, believes in doing mission work with community building as an aim, and works toward capacity building. Lott Carey does mission work around the world with what it calls its “mission partners.” These partners are located in Africa: Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Mozambique, Nigeria, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe; Asia: New Delhi, India and Bangalore, India; The Caribbean: Grenada, Haiti, and Jamaica; Europe: Italy and Turkey; North America: Canada and The United States; Oceania: Australia; and South America: Guyana. Today’s main image is of youth in the Lott Carey Mission School in Liberia. This school provides, at no cost, an education for some of Liberia’s poorest children and gives the students special training in leadership.

Image from the Lott Carey Mission in Zambia

A woman cleaning a Lott Carey-supported church in Haiti

A woman cleaning a Lott Carey-supported church in Haiti

I am particularly excited about the Lott Carey Foreign Mission Convention’s International Youth Development Program (IYD). This program, which has been in existence for 58 years, has as its main goal, “helping churches nurture new generation of leaders for the world. The main program of IYD is its annual youth seminar. Hundreds of young people gather on a college campus and discuss issues of relevance to young people around the world. Most of the attendees are Christians from churches throughout America, and some students come from outside America. The next gathering will be held June 2013.

At these sessions youth are taught what it means to be mission-minded and are provided information on how to be present and future missionaries. The sessions first focus on helping youth understand mission issues such as homelessness and poverty in their context. Then, quite importantly, youth are taught how to advocate for and with others.

Reverend Gregory Davis of Fountain Baptist Church in Summit, New Jersey, is a firsthand witness of youth transformation as a result of the Lott Carey Seminars. For six years he has led more than 100 young people to the summer gatherings. During the sessions, he says, there are two main concepts that he stresses to his group—service through participation and personal development. “Keeping youth engaged is about being relevant and inspiring them into partnerships with communities. It is my responsibility to help them understand their vital role in the Church.”4

In addition to the Youth Program and world mission work, Lott Carey recently launched a new Calling Congregations initiative. This Lilly Endowment-funded program has among its many aims helping young women and men discern calls to ministry through emphasizing the equal importance of journey and destination.

IV. Songs for This Lectionary Moment

Although they are not sung very much today, when I think about world missions, there are two songs that always come to mind—“As You Go, Tell the World” and “Am I a Soldier of the Cross.” The first song is so short and simple that its profundity could easily be missed. It makes us all missionaries, especially if we dare move beyond our comfortable and typical confines. The second song comes to mind because when I was a child, I was taught that a part of being a Christian was to live so that others would come to know Christ everywhere I went. This, I believe, is every Christian’s responsibility no matter the cost.

As You Go, Tell the World

Author Unknown

As you go, tell the world, as you go, tell the world

Tell the world about Jesus, tell them about his love.

Tell the world about Jesus, tell them about his love.5

Am I a Soldier of the Cross

by Isaac Watts

Am I a soldier of the cross,

A foll’wer of the lamb?

And shall I fear to own His cause

Or blush to speak his name?

Must I be carried to the skies

On flow’ry beds of ease,

While others fought to win the prize

And sailed through bloody seas?

Are there no foes for me to face?

Must I not stem the flood?

Is this vile world a friend to grace,

To help me on to God?

Sure I must fight if I would reign:

Increase my courage, Lord;

I’ll bear the toil, endure the pain,

supported by thy word.6

V. Mission Poems and Quotes

Away in foreign lands they wondered how

Their simple words had power.

At home the Christians, two or three,

Had met to pray an hour.

Yes, we are always wondering, wondering how—

Because we do not see

Someone—perhaps unknown and faraway—

On bended knee.

The Spirit of Christ is the spirit of missions, and the nearer we get to Him, the more intensely missionary we become.

| |

—Henry Martyn, missionary to the Muslims of Persia and India |

I am ready to burn out for God. I am ready to endure any hardship, if by any means I might save some. The longing of my heart is to make known my glorious Redeemer to those who have never heard.

Scores of casks! And only one missionary!

| |

—Mary Slessor (1848–1915), pioneer Scottish missionary to Calabar, part of what is

now Nigeria. She made this observation in August 1876 while boarding a ship at Liverpool that

was busy loading casks (barrels) of spirits for West Africa. |

When you think of the woman’s power, you forget the power of the woman’s God. I shall go on.

| |

—Mary Slessor, upon being told by a local African chief that it was foolish and dangerous for her, a woman, to travel inland to intervene between warring tribes. |

We must be global Christians with a global vision because our God is a global God.

God’s part is to put forth power; our part is to put forth faith.

VI. Books on Mission Work Abroad

|

Vaughn J. Walston and Robert J. Stevens , eds. African-American Experience in World Mission: A Call Beyond Community. Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library Publishers, 2003. |

|

de Waal, Alex. Famine Crimes: Politics and the Disaster Relief Industry in Africa. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2009. |

|

Uvin, Peter. Aiding Violence: The Development Enterprise in Rwanda. Sterling, VA: Kumarian Press, 1998. |

|

Fionna. Terry. Condemned to Repeat? The Paradox of Humanitarian Action. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University, 2002. |

Notes

1. Sogge, David. “Foreign Aid: Does It Harm or Help?” The Christian Century. February 23, 2000, 206–209.

2. Edwards, Michael. Future Positive: International Co-operation in the 21st Century. (Oxford, UK: Routledge, 2004). Quoted in David Sogge, “Foreign Aid: Does It Harm or Help?” The Christian Century. February 23, 2000, 206–209.

3. According to Wikipedia, Non-governmental organizations or NGOs are: “Legally constituted organizations created by natural or legal people that operate independently from any form of

government. The term originated from the United Nations (UN), and normally refers to organizations that are not a part of a government and are not conventional for-profit businesses. In the cases in which NGOs are funded totally or partially by governments, the NGO maintains its non-governmental status by excluding government representatives from membership in the organization. The term is usually applied only to organizations that pursue wider social aims that have political aspects, but are not openly political organizations such as political parties.”

4. The Lott Carey Herald. November 2012, p. 7.

5. “As You Go, Tell the World.” Text Anonymous. Arr. by Valeria Foster. African American Heritage Hymnal. Chicago, IL: GIA Publications, 2001. #633

6. Watts, Isaac. “Am I a Soldier of the Cross.” African American Heritage Hymnal. #482

|