GRADUATION SUNDAY

CULTURAL RESOURCES

GRADUATION SUNDAY

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Sunday, June 22, 2008

Juan Floyd-Thomas, Guest Cultural Resource Commentator

Associate Professor of History Texas Christian University, Fort Worth, TX

I. The Black Church Combats Mis-education and Anti-intellectualism

In 1933, African American historian and educator Dr. Carter G. Woodson’s classic text, The Mis-Education of the Negro, was published.

The main argument of Woodson's book is that African Americans were being culturally indoctrinated, rather than taught, in American schools

and this psychological conditioning caused African Americans to believe that they were subordinate and ultimately inferior to white

counterparts in American society. In the most well-known quote from the book, Woodson argues that:

When you control a man's thinking you do not have to worry about his actions. You do not have

to tell him not to stand here or go yonder. He will find his 'proper place' and will stay in it.

You do not need to send him to the back door. He will go without being told. In fact, if there

is no back door, he will cut one for his special benefit. His education makes it necessary.1

Laying bare the crisis of miseducation for generations of African Americans both then and now, he challenges African

American women, men, and children to become lifelong learners who can think and "do for themselves," regardless of what

they were taught by mainstream American culture. In 2000, the revolutionary hip hop artists Dead Prez invoked the educational

theories of Carter G. Woodson in their song, “They Schools,” when they asserted that: “They schools ain’t teachin us, what

we need to know to survive… They schools don't educate, all they teach the people is lies.” 2 By trying to grapple with the

inherent flaws and problems of modern American education, the members of Dead Prez attempt to illustrate the ways in which

the intellectual promise and human potential of countless black youngsters and teenagers are routinely undermined, by an

educational system that remains fundamentally threatened by African Americans who are intelligent and independent thinkers.

As important as it is to address miseducation, a more disturbing issue that permeates much of contemporary African American culture

has surfaced in the form of anti-intellectualism. This trend is most notable when notions of academic excellence among black youth

are being denounced by certain youngsters as “acting white.” As a college professor who deals with young black women and men in

their late teens and early twenties on a regular basis, I must state that what is most troubling about this negative attitude

towards education is when young people who have access and opportunity to pursue higher learning disparage the process for fear

that it will further alienate them from their peers. One example of this situation is evident with one of the brightest, most

successful stars of the hip-hop generation, Kanye West. With the blockbuster commercial success of his critically acclaimed debut

CD, College Dropout (2004), Kanye West not only established himself as a major force within the music industry but

came to be viewed (rightly or wrongly) as an advocate of African American anti-intellectualism. From its title to many of its

key lyrical comments, Mr. West expresses great frustration and resentment at institutions of higher education while taking pride in his

own success as a hip hop artist and music producer. Even though West’s intelligence and ingenuity are clearly evident, his rejection

of college education is quite alarming given the fact that his late mother, Dr. Donda West, was a college professor. Moreover, many

of his young fans applaud his aversion to formal education without recognizing that he has inexhaustible ambition, and a strong sense

of purpose. Both of which, by the way, are essential to excelling at educational pursuits, and gave shape to his willingness to

engage in apprenticeship, a form of education, for a number of years to sharply hone his craft. Anti-intellectualism is certainly

not limited to African Americans, but in light of the highly negative experiences many African Americans encounter within mainstream

American education, the effects of rejecting the educational process altogether can be nothing less than devastating.

Graduation Sunday serves as an important step towards affirming the importance of formal education within the African American experience.

In today’s world, the declining significance of formal education for black youth has to be combated by the contemporary black church

in terms of both miseducation by whites, and anti-intellectualism amongst African Americans. As much as the graduation of individual

students at various levels of education from kindergarten to college is a great moment for the student’s family, the event has even

greater impact on the African American community that ought to be acknowledged and celebrated to the utmost. Given that reality,

the local church must be central in praising students’ accomplishments, while also reinforcing the idea that academic achievement

is a worthwhile endeavor.

II. Historic Black Colleges and Universities

A. Seen by black church leaders as a tool for removing the social, economic, cultural, intellectual, and

emotional shackles of inhuman bondage in this land, it has been and continues to be typical for black churches

and denominations to establish schools of various levels. Much like public boycotts, lawsuits, and organized

grassroots protests, establishing and maintaining schools has been nothing less than a strategy of resistance

and survival by black churches on behalf of the larger community. Historically, schools for freed people were

established since Reconstruction in order to empower and enlighten African Americans who would otherwise be

miseducated by white American institutions. Prime examples of this are Historic Black Colleges and Universities

(HBCUs). While different black denominations varied in their educational enterprises and approaches, for majority of black denominations education has long been acknowledged for its capacity to equalize social and economic

inequities. In the early AME church, for example, “the church leaders were not educated people, but they had a

clear perception of what education would mean to the interests of the church and the advancement of the African

people then held in abject slavery. Bishop Daniel Payne, who had been a schoolmaster in Baltimore, set the

educational goals for the fledgling institution by insisting upon trained ministers, and by encouraging

AME pastors to organize schools in their communities as an aspect of their ministries.” 3

Denominations have established HBCUs and local churches have established nursery, elementary and secondary schools.

Along with the help of white allies, African American church denominations established schools, colleges,

universities, and seminaries during and after slavery. There are approximately 110 institutions

listed on the U.S. Department of Education’s website concerning the White House’s Initiative on HCBUs including

public and private institutions such as: Wilberforce University, Lincoln University, Florida A&M University,

Prairie View University, Tuskegee University, Grambling University, Bethune-Cookman College, American Baptist

College, Hampton University, Spelman College, Fisk University, Morehouse College and the Interdenominational

Theological Center among others. From humble roots, many of these freedmen’s schools evolved gradually into the

HBCUs which laid the foundation for the creation of an educated black middle-class.

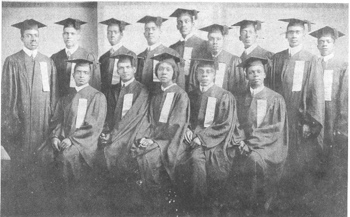

[ Livingstone College graduates circa 1906]

B. Following are some notable examples of schools founded by African American denominations

1863 - Wilberforce (AME)

1870 - Allen University (AME)

1877 - Livingston College (AMEZ)

1877 - Natchez Seminary (later Jackson College, later Jackson State University) Baptist Missionary Convention)

1881 - Morris Brown (AME)

1881 - Paul Quinn College

1883 - Paine College (CME)4

III. Primary and High Schools

African American denominations also founded primary and high schools. Henry Mitchell writes,

“In the case of both primary and secondary schools, their church-based schools bridged the gap

the white-sponsored schools could not close until the day of public schools. A.M.E.’s, A.M.E.Z’s,

and C.M.E.’s as well as African American Baptists, all boldly took on the more reachable goal of

primary and then secondary education.”5 Mitchell’s book, Black Church Beginnings, lists more

than seventy-five schools, including primary, secondary and colleges, that were totally formed by

African Americans, or were formed by them in conjunction with white allies.

1879 - Pettey High School, NC (AMEZ)

1887 - Greenville, Tennessee High School (AMEZ)

1891 - Ashley County High School, Arkansas (AME)

1893 - Greenville High School, TN (AMEZ)

1894 - Clinton Institute, SC (AMEZ)

1906 - Indian Mission High School, Boley, Oklahoma (CME)

1907 - CMEs combined Booker City High School and Thomasville High School in Birmingham

1908 - Helen B. Cobb Institute for Girls, Barnesville, GA (CME)

1919 - Johnson Rural High School, MS (AMEZ)6

IV. Academic Accomplishments as Sacred Duty

Many local churches have demonstrated a deeply ingrained ethos that encourages education.

Local churches will typically have congregational programs which support and affirm the educational aspirations and

achievements of members. Churches provide scholarships to college and graduate students, tutorial programs, SAT training,

and weekend trips to visit colleges and universities for young people trying to decide which schools to attend.

In the spring, many churches have a celebration during Sunday worship (sometimes called Recognition Sunday or

Education Sunday) where graduation from elementary, high school and college is recognized. During this service,

graduates receive scholarships and tuition assistance from the church as commemoration for their academic accomplishments.

V. Kente Graduation Blessing Ceremony

Kente cloth is now recognized throughout the world

as quintessentially African cloth, with its bright colors and bold patterns appealing to African and Western eyes

alike. Kente originates from West Africa where we as a people were discovered, captured, and enslaved.

Traditionally woven by men and dyed by women, as those who were assigned the role of holding the fabric

of the community together, kente appears in a variety of ceremonies and rituals ranging from funerals,

marriages and initiation rites to harvest blessings and gifts. It is also used in shrines and sanctuaries

to pay homage to the Creator God. In these ways, the kente cloth seems to be an integral part of many aspects

of both daily and ritual life.

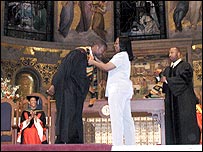

Kente blessing ceremony at Stanford Memorial Chapel in 2003

This kente stole shown above is presented to graduating students who have helped to hold together the fabric of the black community.

Like this cloth, the students are being recognized as young women and men of tightly structured integrity and recognizable beauty,

who have maintained lives that have been set and established by a God who promises us freedom beyond enslavement. Adorning the

students with kente stoles reflects their royal patronage as they stand on the shoulders of their ancestors in order to claim

the prize for which they have sacrificed much and inherited much, namely the degree. Like their ancestors before them, the

progress of the entire community will be known through the succession of students who seek to follow the road and press to the

mark of a higher calling.

So Members of church families gather in the sanctuary or a likewise designated space in order to consecrate this day. Both the

ceremony and the cloth illustrate the important role of leadership, and the need to exercise it appropriately. In this fashion, the

students being honored on Graduation Sunday are bright kings and queens standing in the presence and with the blessing of our ancestors,

our community, the African American family, and our good name. Following is a prayer that accompanies the draping of the stoles.

We now bless you with the power of the Lord our God, Christ our Savior, and the Holy Spirit our Comforter to give you the push you

need to go out into the world to go your own way, do your own thing, and live in such a way that neither God, nor your people, will ever

be ashamed for having celebrated you today.

Notes

- Woodson, Carter G. The Mis-Education of the Negro. 1933. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1990.

- Dead Prez. “They Schools.” Let's Get Free. Manchester, England: Relativity Records, 2000.

- Lincoln, C. Eric and Lawrence H. Mamiya. The Black Church in the African American Experience. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1990, pp. 52-53.

- Mitchell, Henry H. Black Church Beginnings: The Long-Hidden Realities of the First Years. Grand Rapids, MI: WM B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004. p. 156.

- Ibid., pp. 156-161.

- Ibid., pp. 157-159.

|