|

MEN’S DAY

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Sunday, July 29, 2012

(Please see the extensive and provocative video below featuring James Baldwin and Dick Gregory titled "Baldwin's Nigger.")

Danté R. Quick, Guest Cultural Resource Commentator

Ph.D. Student, Graduate Theological Union and Senior Pastor, Friendship Missionary Baptist Church, Vallejo, CA

I. History

Theology and sociology are intricately intertwined in the understanding of any religious tradition. As such, Men’s Day in the African American tradition has historically been an occasion by which African American institutions of faith come together to proclaim and reclaim the notions of masculinity which find their witness in Scripture and tradition.

However, one must realize that there is a great difference between tradition and traditionalism. Tradition is informative and grounding. It offers direction based upon the testimony of time. Traditionalism attempts to trap time into a stagnate box of rigidity. It is threatened by innovation and growth. It strives to strangle the Spirit’s sovereignty which finds its ultimate expression in creative freedom. Therefore, Men’s Day is a time in which institutions of faith are called to celebrate, challenge, and create.

Theologically, Men’s Day has yearly offered congregations the opportunity to reflect upon those foundational characteristics that where present in the Hebrew term

(transliterated as ‘adam) or man. It is in the creation account of the book of Genesis that we are told, “Then God said, ‘Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness’” (Genesis 1:26a, NRSV). Theologically, this image of God in God’s self stands as the perfect combination of Creator, Incarnate, and Spirit in a diverse, loving, powerful, and interconnected union. By extension, that image of man pre-fall stood as one who personified these very same divine qualities. And those very same qualities broke out of the encasement of sin and found expression in the creativity of Countee Cullen, the mysticism of Howard Thurman, and the spiritual dynamism of Martin Luther King, Jr. (transliterated as ‘adam) or man. It is in the creation account of the book of Genesis that we are told, “Then God said, ‘Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness’” (Genesis 1:26a, NRSV). Theologically, this image of God in God’s self stands as the perfect combination of Creator, Incarnate, and Spirit in a diverse, loving, powerful, and interconnected union. By extension, that image of man pre-fall stood as one who personified these very same divine qualities. And those very same qualities broke out of the encasement of sin and found expression in the creativity of Countee Cullen, the mysticism of Howard Thurman, and the spiritual dynamism of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Sociologically, this divine image has historically been tortured by the sin-filled twin cousins of race and capitalism. Swathed in a seductive and self-serving form of Western Christianity, black men were constructed not in the divine drapery given to them by their benevolent parent, but swaddled in the hyper-sexualized suit of a savage.

|

|

It was 19th century Methodist minister and theologian William Pope Harrison who first put forth a comprehensive formulation of these notions in his 1893 The Gospel Among the Slaves: A Short Account of the Missionary Operations Among African Slaves of the Southern States:

But the African, as a savage, transported to America, must bring the sins and vicious nature which belong to his people and his tribe. The foolish dream of a virtuous savage, communing with nature, and rising to the highest altitudes of virtuous humanity, has long been dispelled, as nearer acquaintance revealed to the world the truth. The fearful picture of the heathen who knows not God, as given by St. Paul in the first chapter of the Epistle to the Romans, is as true to-day as in the day in which it was written.1 |

As Harrison also served as the 48th chaplain of the U.S. House of Representatives, his legacy falls within the great American tradition of interweaving race and governance. This “traditionalism” can be found alive and well in the American cultural mainstream today.

Recent history has been no kinder to African American men. Even with the rise and celebration of the quintessential image of African American manhood to the highest office in the land, President of the United States, African American images of masculinity have not improved. The heterosexual Harvard law graduate, husband to one wife, father of two, who happens to be a Christian Protestant, has been forced to prove his place within American exceptionalism in a manner which brings Langston Hughes’s “I, Too, Sing America” back to relevance!

|

|

Upon deplaning Air Force One, President Obama was greeted by the disrespectful wagging finger of Arizona Governor Jan Brewer. Who would have imagined a day in America when the President of the United States would be addressed with such demeaning and disrespectful terms. Recently, U.S. Congressman Doug Lamborn of Colorado on a talk show referred to President Obama as a “tar-baby.” Presidential candidate Newt Gingrich referred to the President as the “best food-stamp presidentin American history.” And who can forget the caricature of the first African American President dressed as a witch doctor. |

Imagine, when members of a nation look upon a man who embodies the accomplishments of the highest ideals of the land with such disdain, how it would treat his less-privileged brother. The answers are startling. According to The Morehouse Male Initiative, of all African American children born in the year 2003, 29% are expected to spend some time in jail/prison. “Black men earn 67% of what white men earn. 53% of Black men aged 25–34 are either unemployed or earn too little to lift a family of four from poverty.”2

Since we have established that theology and sociology are intertwined, we must also conclude that psychology is impacted by the belief systems and structures out of which we operate. In light of its historical relationship with the American context, it is clear to see that one of the major factors in the way that African American men and the community are formed and struggle to survive is racism. Robert Terry informs us that in all of its cultural manifestations, “racism is any activity by individuals, groups, institutions, or cultures that treats human beings unjustly because of color and rationalizes that treatment by attributing to them undesirable biological, psychological, social, or cultural characteristics.”3 Race is the prevailing factor in the construction of human relations in the American context.

Hence, for African American communities, within the interpretive process, methods of resistance and liberation are the central concerns. Key to the concept of liberation is the idea of identity. Cornel West is enlightening in this regard as he posits, “Black self hatred and hatred of others parallels that of all human beings, who must gain some sense of themselves and the world. But the tremendous weight of white supremacy makes this human struggle for mature black selfhood even more difficult.”4

|

|

If the African American Church is to remain relevant, Men’s Day must stand as a seminal moment in countering the self-hatred that is finding expression in the way masculintity is being developed within our cities. Among a generation of youth and young adults who hold less and less regard for life, a dysfunction and demonic masculinity has developed and metastasized into murder. Men’s Day offers the Church the opportunity to inform and transform. It is a day for us to explore the strong traditions of the African American male presence within families and communities while rejecting the tedious tradionalism that finds its roots in fear. |

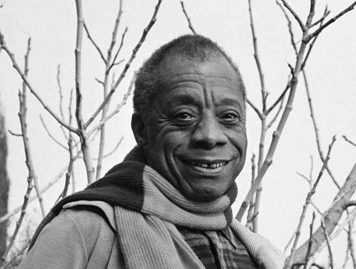

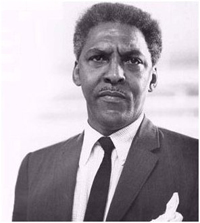

Theologian James Cone argues, “The black church has been radical, serving as the most important instrument of black liberation, but it has also been one of the most conservative institutions in the black community. This is the paradox.”5 Men’s Day offers us the opportunity to look beyond the paradox and seek strength in rich resources that have long been ignored in such black men as James Baldwin and Bayard Rustin.

|

|

|

| James Baldwin |

|

Bayard Rustin |

II. Autobiographical Moment

I am the product of unwed parents from the inner city of Washington D.C. Unfortunately, out of the nine childhood friends I ran the streets of D.C. with, seven are victims of those same streets. Yes, we came of age in the era that gave birth to a new drug called “crack.” Yet, most of those, who unlike me were not as fortunate to make it out of the tough streets, were addicted to a lack of vision and low esteem long before they found the little white rock. Yes, in the midst of the most powerful city in the world, I, like so many today, experienced the Duboisian reality of double consciousness. “To be or not to be” was not just a rhetorical question born from a Shakespearean remembrance, but it was a cold reality that one navigated just to walk to school and back safely.

No, I am not one who can say that I have been committed to Christ since my earliest childhood. In honesty, my Christian commitment is born out of a radical meeting with God at the place where the completeness of my brokenness met God at the throne of grace. Theologian, mystic, and philosopher, Rev. Dr. Howard Washington Thurman sums up this experience best when he writes,

The only thing I do know is that something happens to you when you become aware of another’s love that releases you, that frees you. You relax even your need of privacy. You share the quality of your concern and your aspirations, your doubts, your limitations, with quiet confidence that whatever defects you reveal, the loved one will help you remove them from your life. The fault which you have covered up, lest its exposure give to another what could become, in his hands, an instrument of violence, now becomes one of the creative means by which the quality and the integrity and the character of your life are improved and enriched.6

My conversion experience is personified by this statement. I was blessed with men, dead and alive, biological and not, who played a major role in the process. In fact, I had Thurman’s words read publicly at two of the most momentous experiences of my life—my father’s funeral and my wedding. In both the experience of death and life, I attempted to remind myself and express to others that my life is an experiment in living this redemptive love in the midst of suffering and celebration. To this end, as a black man, Christian commitment for me is expressed in a lifestyle, a lifestyle of liberation. This style of living is first and foremost expressed in the prayer I have prayed every day for ten years, “Lord, help me to stay clothed in the garments of humility.” In staying committed to the principle of humility, I, like the writer of the 25th Psalm, recognize that my chance of staying connected to the internal presence of God is heightened. Through this internal connection, Christ is resurrected daily through the witness of my life.

It is the same sense of humility that informs me that I fall short of God’s will for my life daily. Hence, this sense of failure and salvation through unearned grace is what leads me to the desire to grow in my faith daily. I view Christian growth as the alternating experience of victory and loss in the pursuit of a goal that cannot be fully realized until the day God reclaims you in the land of God’s glory.

My life and my view of it for many years were shaped by what was termed a learning disability, dyslexia. By the time I reached fourth grade, I was illiterate, saddled with the yoke of low self-esteem and alienation from those with potential. I was placed in the back of the classroom in Washington, D.C.’s public schools, where there was no view of God. I was, however, aware of the unconditional love found in a one-bedroom apartment from my mother and grandmother. After being diagnosed, I was placed in St. Benedict the Moor, a small Catholic school in northeast Washington, D.C. There I was introduced to God. For the first time someone outside of my home and family believed in my future and me. No longer was I relegated to the back of the room. Although I knew God’s name, God still had no conscious manifestation in my life. At sixteen I was still trying to learn how to tie my shoes without assistance.

My high school years were spent with Christian Brothers at St. John’s College High School, an all-male military high school. Although God was there and always being talked about, I still had no relationship with God. Where was God on the cold mornings while I was dressing next to the gas stove? I viewed myself as the only savior on which I could rely. It was up to me to make it, so that I could lead my family out of poverty to freedom. As I excelled, the credit was placed squarely on my shoulders. While in high school I was elected to the Citywide Youth City Council. My role model became Washington, D.C. Mayor Marion Barry. Through my association with Mayor Barry I was introduced to and recruited by Alumni from Morehouse College. By the time I made it to Morehouse College my life was radically altered. All but one of my friends had been killed, and I felt I had made it. I viewed myself as a giant. Though I participated in Communion once a week, God was now a ritual, external to my view of self.

While at Morehouse I had the privilege of becoming a Congressional Black Caucus/Philip Morris Scholarship recipient at the end of my freshman year. This program afforded me the opportunity to work with Congressman John Lewis. However, it was at Morehouse that I was once again confronted with being dyslexic. This was compounded by the loss of two close family members and financial difficulties. This battle was different from those that the streets of D.C. presented. Now I had to fight with my mind (and in retrospect, spirit). My view of self was small and defeated. I saw myself through the lenses of fear, and God . . . left with the ritual. I did not understand the God I heard about every Tuesday and Thursday in the Chapel at Morehouse College. Esteemed pastors/theologians such as the Rev. Drs. Calvin Butts, Otis Moss, Jeremiah Wright, and Charles Adams spoke of their God with eloquence and power. Their God sounded good, however for me God had no relevance and was not present.

I did not return to Morehouse for my junior year and I began to work full-time to help support my mother and grandmother. Feeling depressed and oppressed, my view of self was about to undertake a radical transformation. In April of 1992, I walked into a small Baptist church. The sermon that day would alter my view on Jesus. The pastor preached of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane. Finally, I could identify with God. God seemed real. It was during this sermon that I became acquainted with the two foundational influences of my spiritual development, the Rev. Drs. Aaron L. Parker and Howard Washington Thurman. During his sermon Dr. Parker, who would become my spiritual father and mentor, referenced statements from “Disciplines of the Spirit” by Dr. Thurman. I bought the book two days later and what I read would change my life.

Dr. Thurman’s thoughts on growing in wisdom and stature, prayer, forgiveness, and suffering spoke to my experience and allowed me to view my life with a spiritual eye. On July 19, 1992, I gave my life to God and was baptized. It is on this day that I, like the psalmist, had to cry to the Lord, “For your name’s sake, O Lord, pardon my guilt, for it is great. Who are they that fear the Lord? He will teach them the way that they should choose” (Psalm 25:11-12, NRSV). It was the deacons of the church who adopted me as a grandson and son and gave me wisdom that has been passed down through the ages. It was a pastor who nurtured me and never violated the trust of his sacred office. As a pastor and scholar in training, men such as Drs. J. Alfred Smith Sr. and James Noel now nurture me, as did Dr. Parker and those deacons.

III. Poetry for This Lectionary Moment

The current economic crisis is impacting African American urban communities in a drastic and dire fashion. Currently, I pastor in the first major city (Vallejo) in the state of California to file for bankruptcy. We suffer from the typical economic maladies that impact not only the economic condition of black men, but are also damaging to the emotional and spiritual health of the entire community. Every day, I watch young black men gather outside my church for hours at a time engaged in all kinds of activities that go against their short- and long-term best interests. Men’s Day provides a prime opportunity for the Church to become relevant to their plight. The following lection aids are intended to assist the user in reaching the community of faith via a variety of means.

As the African American Church has been the center of the community and its fight for personhood, theologian James Cone helps us to understand the centrality of the preacher’s ability to cast a new vision of hope for an oppressed community: “In Black churches, the one who preaches the Word is primarily a storyteller. And thus when the black church community invites a minister as a pastor, their chief question is: ‘Can the Preacher tell the story?’”7 Men’s Day is the opportunity for the story to be told via the assistance of poetry, prose, and song.

I Too

by Langston Hughes

I, too, sing America

I am the darker brother

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

Tomorrow

I’ll sit at the table

When company comes.

Nobody’ll dare

Say to me,

“Eat in the Kitchen,”

Then.

Besides,

They’ll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed---

I, too, am America.8

Mother to Son

by Langston Hughes

Well, son, I’ll tell you:

Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.

It’s had tacks in it,

And splinters,

And boards torn up,

And places with no carpet on the floor --

Bare.

But all the time

I’se been a-climbin’ on,….And reachin’ landin’s,

And turnin’ corners,

And sometimes goin’ in the dark….Where there ain’t been no light.

So boy, don’t you turn back.

Don’t you set down on the steps

‘Cause you finds it’s kinder hard.

Don’t you fall now --

For I’se still goin’, honey,

I’se still climbin’,

And life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.9

Both poems point to the desire for acceptance and liberation even as one struggles in humility. Like the Psalmist, on this Men’s Day we must abide in an undying trust in God. We must demonstrate our resolve to keep our eyes towards the Lord, for he will do great things for us. Inasmuch as we have faith, we must live faith. “They will abide in prosperity, and their children shall possess the land. The friendship of the Lord is for those who fear him, and he makes his covenant known to them. My eyes are ever towards the Lord, for he will pluck my feet out of the net” (Psalm 25:14-15, NRSV).

IV. Making This a Memorable Learning Moment through Prose

At a retreat gathering with men of various ages, I asked each man to offer a word which for them expressed the essence of what it meant to be a man. After receiving a word from each man, we then used them to construct a statement that represented our collective commitment toward growth. The exercise is an excellent way to stimulate conversation. Note that the words in red represent the key words that were offered by the men. Each man then signed the statement and agreed to hold each other accountable for their progress. Our lection Scripture would make a wonderful starting point to begin the conversation.

WORDS FROM THE MEN

Regret. We the men of Zion Hill have declared war on regret. Regret is defined as feeling sorry or distressed about something. Regret is a lost opportunity. Regret is an unspoken word. We the men of Zion Hill have chosen several words that speak to our souls’ aim for the future. However, we realize with a great sense of humility that these words not fully actualized in our hearts, lead to regret!

How will we combat regret? With a great deal of enthusiasm, we now surrender all of our pain, anger and despair to the one with all power to heal, knowing that God’s love shall conquer and restore. As men we must begin to examine with courage our relationships and, in truthfulness, live our lives serving without expectation of return, teaching all who come in our midst by being a living example of the life of Christ.

This, we acknowledge, requires much work and consistency. Our families, church and selves are in dire need of our leadership. This means more than fiery words; it means complete and utter devotion. Devotion to God and thereby the bright eyes of the future, strong arms of our present and the sweetness of those who say, “I love you.” Through fellowship, we the men must step forward and trust the Lord.

In unity we must agree that giving is a prerequisite for entrance into the Brotherhood. We must be giving of our time and our love. Then we can accept the joy in teaching a boy to be a young man and the value of training a young man to be a responsible adult.

With an intensity and determination to destroy the devil and create community in the broadest sense of the word, we must submit. In God’s time and in God’s way, our rough roads will be made smooth and our lives complete. Regret…not with the Rebirth of the Brotherhood!!!

BY SIGNING THIS DOCUMENT, I HEREBY AGREE TO STRIVE PRAYERFULLY FOR THE ACHIEVEMENT OF THE ABOVE STATED GOALS AND THEREBY COMMIT TO THE ABOLITION OF THE DEVIL’S WEAPON OF CHOICE—REGRET!

PRINT NAME:________________________ SIGNATURE:__________________________

V. A Story to Illustrate the Lection

In Fire in the Belly: On Being a Man, Sam Keen offers a story that is reminiscent of the plea in the 25th Psalm. While in emotional turmoil, Keen enlisted the counsel of Howard Thurman for relief. Thurman told this story:

Once there was a man who loved a woman beyond all measure. He sailed away and one day came to an uninhabited island. Leaving her on the boat, he explored the interior, and deep in the forest he came upon a stone image of an unknown God. It radiated such a sense of power that he fell on his knees and prayed for his beloved: ‘May her life be full and happy. May our love be fulfilling for her.’ As he headed back he came to a hilltop, and as he looked out across the water he saw his boat and his lover sailing away. His prayer had been answered.10

Thurman ended by offering Keen this advice, “There are two questions that a man must ask himself: The first is ‘Where am I going?’ and the second is ‘Who will go with me?’ If you ever get these questions in the wrong order you are in trouble.”11

Three things must be pointed out as it relates to the 25th Psalm. First, men must be able to seek in earnest humility. Second, God is for the “good and upright” and will hear the prayers of those consistent in seeking God’s counsel. Third, men must stay focused on God and not get lost in false idols. Often black men can place the love and devotion of another above the covenant that must be entered into and maintained with God.

VI. Songs for This Lectionary Moment

Within the broader African American faith community, music (various genres) is a critical aspect of worship. The 25th Psalm calls men to be humble and committed to God. This call is directed to a loving and faithful God who directs the believer down the right path. The act of worship through song invites men to offer praise to God in genuine belief that God will reveal God’s direction and purpose in our lives. The Psalmist is reaffirming his commitment to God. Such commitment must be steeped in a desire for forgiveness and direction. The following songs offer entrance into a similar mode of worship.

I Need Your Glory

Chorus:

I need your Glory

I want your Glory

Less of me and more of you is what I need

Show me your Glory

Show me your Power

Less of me and more of you is what I need

Lead:

So many times I strayed away, rejecting you

And your warm embrace

I realized that I need you more and more each day

Chorus:

I need your Glory

I want your Glory

Less of me and more of you is what I need

Show me your Glory

Show me your Power

Less of me and more of you is what I need

Lead:

If there is a worshiper out there that will join me

come on let him know that you are hungry for him,

that you are longing for him, that you are thirsting for him, oh yeah,

--- lift up your voice and sing

I need you, I can’t live without you, Lord, I need your glory.

I need to live right, to get it right, I need your

I need your shekinah glory, yeah------------

I need you rain on me, flow on me, shine on me, your glory.12

In Your Will

Chorus:

I won’t give up or give in

I will keep on till the end

I will keep steadfast, unmovable

Always abounding in you

Lord I am standing in your will

Bridge:

I’m standing in your will. I’m standing Lord

I’m standing in your will. I’m standing

I’m standing in your will. I’m standing Lord

Said I’m staying in your will

Promise you Lord I’m standing in your will.13

My Father Was/Is

Who was there when I first opened up my eyes?

And who was there to heal the hurt

when I first learned to ride?

and who would never miss a game?

celebrate me won or loss?

yes my Father was

When adolescent years had come who helped me understand?

and when the winning point was scored

who in victory raised my hand?

and when I hung my head in shame

who was there to lift it up?

yes my Father was

My Heavenly Father has always been there

for my earthly one was gone yeah

He’s taken care of me

and I only want to be just like Him

Now that I’m a full grown man

who can wipe my tears away?

and who’s on the other end

when I lift my heart to pray?

and who’s always by my side

to help me make it through?

yes my Father is

my Heavenly Father is

yes he is

yes my Father is…14

VII. Audio Visual Aid

Men’s Day offers a great opportunity for African American congregations to explore the social issues that retard the development of healthy masculine images. The challenges we face today are not new. From the Harlem Renaissance’s New Negro, to the debate over “Black or African American,” to Tigers Woods’s construct of “Cablinasian,” African Americans have been in a continuous conversation over identity, for identity coincides with social norms and ethical formation. History offers us clues into our future in this regard. As such, I am amazed at how potent historical ignorance is in obstructing images of masculinity that are not emotionally stunted and anchored in an abyss of anger.

With this in mind, churches must be communal incubators for the creation of healthy self-consciousness. This means that churches must become revolutionary spaces of education. In this regard, in his essay “Is It Useless to Revolt?” the French philosopher Michel Foucault is informative in this clarion call to African American houses of faith:

Some movements are irreducible: those in which a single man, a group, a minority or a complete people asserts that it will no longer obey and risks its life before a power which is considered unjust…In the end, there is no explanation for the man who revolts. His action is necessarily a tearing that breaks the thread of history and its long chains of reason that a man can genuinely give preference to the risks of death over the certitude of having to obey.15

Remember, the goal on Men’s Day is to celebrate, inform, and transform. Yet Men’s Day is not without its challenges. As an educator and a pastor, I have come to understand that there are as many learning styles within a congregation as there members. Indeed, no two people process information in the exact same fashion. The learning process can be stimulated by various media. As such, some might encounter the giant intellect of James Baldwin by his written works, while others would benefit from watching and listening. The following video would create a wonderful foundation for a men’s discussion group.

James Baldwin and Dick Gregory: Baldwin’s Nigger (1969)

Notes

1. Harrison, William Pope, ed. The Gospel Among the Slaves: A Short Account of the Missionary Operations Among African Slaves of the Southern States. New York: AMS Press, 1893. pp. 99–100.

2. Terry, Robert. For Whites Only. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1970. p. 41.

3. Ibid.

4. Gates, Henry Louis, Jr., and Cornel West. The Future of The Race. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996. p. 95.

5. Cone, James H. For My People: Black Theology and the Black Church, Where have we been and where are we going? Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1984. p. 100.

6. Thurman, Howard. The Growing Edge. Richmond, IN: Friends United Press, 1956. p. 66.

7. Cone, James H. God of the Oppressed. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1975. p. 57.

8. Hughes, Langston. “I Too.” Online location: http://www.poemhunter.com/poem/i-too/ (accessed 12 February 2012).

9. Hughes, Langston. “Mother to Son.” Online location: http://www.poemhunter.com/poem/i-too/ (accessed 12 February 2012).

10. Keen, Sam. Fire in the Belly: On Being a Man. New York: Bantam, 1992.

11. Ibid.

12. Pugh, Earnest. “I Need Your Glory.” Earnest Pugh: I Need Your Glory. New York: WorldWide Music, 2011.

13. Caree, Isaac, and Lowell Pye. “In Your Will.” Men of Standard: Feels Like Rain. Muscle Shoals, AL: Muscle Shoals, 1999.

14. Hammond, Fred. “My Father Was/Is.” Fred Hammond and Radical for Christ: Purpose by Design. New York: Zomba, 2000.

15. Foucault, Michel. “Is It Useless to Revolt?” in Jeremy R. Carratte ed., Religion and Culture: Michel Foucault. New York: Routledge Inc., 1999. p. 131.

|