Cultural Resources

| |

|

|

|

|

STEWARDSHIP OF TITHES AND TALENTS

CULTURAL RESOURCES

STEWARDSHIP OF TITHES AND TALENTS

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Sunday, May 18, 2008

Juan Floyd-Thomas, Guest Cultural Resource Commentator

Associate Professor of History, Texas Christian University, Fort Worth, TX

I. History and Background

Arguably, tithing first appears in the book of Genesis wherein Abraham gave "a tenth" to Melchizedek, King of Salem,

and the practice is scattered throughout the Bible. In practical terms, the tithe was an offering of one’s

agricultural produce to the Lord as an expression of thanks and dedication for such a bountiful yield during the time

of harvest. Understanding that the ancient world described in the Bible was largely an agricultural economy,

one must also understand that tithes were historically paid not in cash, gold, or luxury items, but rather in crops or livestock.

For additional historic information on tithing, see the lectionary commentary for today.

Current Financial Tithing Issues – The New Backdrop

In today’s more complex economy, we commonly think of financial tithing as “ten percent” of our gross earnings typically to be paid on

the first Sunday of a particular month. Presently, the practice of tithing has become more open to debate and reinterpretation than ever

before. For instance, should a family give ten percent of its household income or a tenth of just one salary? Are modern financial

arrangements such as child support, settlements from lawsuits, insurance claims, or alimony subject to tithing? Should members

calculate their tithes and offerings before or after taxes? Is it more appropriate to tithe to the local church or send donations

to broader ministries that worshippers encounter via the radio, television, and/or internet? Perhaps as we are settling these issues

we will also determine how many hours of our time we need to give to God as

we use our talents to God as we tithe our talents (singing, writing,

ushering, teaching, coaching, etc.) in ways that uplift God and aid the

church and community.

II. Financial Giving In the Black Church

According to the Washington Post's study of 2002 IRS data, across the broad range of faith communities and traditions, religious institutions

account for three out of every four dollars (seventy-five percent) of the nation's money given as charitable donations. Within the

African American community, however, that estimated figure is closer to nine out of every ten dollars.1 A recent survey conducted by the

Gallup Organization on behalf of the Interdenominational Theological Center (ITC), the historically black consortium of seminaries in

Atlanta, Georgia, indicates that roughly forty-five percent of African American church members tithe on a regular basis.2 Another survey,

conducted by the Program for the Study of Organized Religion and Social Work at the University of Pennsylvania, has found that African

American churches derive almost half their income from offerings, and a third from tithes and dues.

Long before government programs were in place, in order to help the poor and the needy within the black community, black churches

were responsible for assisting their congregations with everything from food and shelter during Reconstruction, to legal assistance

and meeting places during the height of the Civil Rights Movement. Money dropped into the offering plate wasn't just for the

building fund. Using benevolent offerings, local black churches were resource centers that paid utility bills for the working poor,

unemployed, and disadvantaged women, men, and children in the surrounding community (often these funds were available based on need

rather than church membership although such outreach was seen as an enticement to attract the unchurched) at times when no other

help was forthcoming. Along with this financial generosity, church folk also used to offer their talents, big or small, in

service of the church and their neighbor. It was not rare to have an elder’s house painted by men from the church or to have

women sew clothing for those without clothes. A recent example of the

churches’ benevolent activity is seen in the mobilization of black

churches in response to the devastation of Hurricane Katrina. They

responded because there was a natural disaster and because of the

government’s slow and limited response through its Federal Emergency

Management Agency (FEMA).

III. A Gospel of Prosperity or a Gospel for Posterity?

In the black church tradition today there is a increasing tension over whether there should be emphasis on a “gospel of prosperity” or,

what I refer to as a “gospel for posterity.” In other words, the dilemma is whether the preached and lived Word of God is intended to

build up individual luxury,or is it supposed to establish a communal legacy. These issues certainly do not have

to be mutually exclusive. However, the fact that there seems to be an overabundance of the former, to the growing exclusion of the

latter, is a genuine cause for worry in many segments of the African American community. I approach this matter from an admittedly

atypical church background, especially regarding the matter of how money and faith relate to one another. As the son of Jamaican

immigrants living in northern New Jersey, I was born and raised Roman Catholic for the first twenty years of my life. During

the 1970s, my immersion into that church context became much deeper once my parents made the decision to transfer me from the

local public school to attend St. Theresa’s Roman Catholic School in Paterson, New Jersey, the parochial school attached to our parish church.

This situation seems relevant to this conversation in three key ways.

First, the tuition dollars spent by the students’ families were not seen as an awful burden (although the cost of such schooling

certainly was expensive for a hard-working family like mine), it was seen as a serious investment both in the education of the child

as well as the work of the church. Next, there was the built-in expectation that, because this was an outright sacrifice for my

struggling family and others like us, the child had to make the overall efforts and investments of the family worthwhile by behaving

well and getting the best grades possible. Lastly, the church took deliberate measures to remind the parents and students that,

as James 2:17 states, “faith, without works, is dead.” In that spirit, my local parish church emphasized this lesson in ways directly

related to stewardship. One example was related to the church’s school. In exchange for a relatively minor discount (five-ten percent

of the overall tuition bill if memory serves correctly), the parents of the schoolchildren were expected to volunteer their time in

some capacity to guarantee the furtherance of the church as well as the school. There were a variety of volunteer tasks that could

be taken up given the time constraints, skills, and preferences of the parents—anything ranging from working in the cafeteria, managing

the library, or working at the school’s weekly bingo games to name a few—but there was only one ironclad rule: no one could get out of

doing their fair share. Even though I have long since left the Catholic church to become Baptist, I will never turn away from the

training and underlying principles that I learned about that sort of pride and responsibility in terms of using our monetary

resources to ensure and expand God’s work here on earth.

In recent years, the concept of stewardship in terms of tithing and use of talents as forms of biblical obligation and community service

has, unfortunately, given way in some churches to an emphasis on giving under the belief that the members will prosper financially

in return. There has been the perennial worry, and perception, of black church leaders growing rich on the proceeds of their

ministry. We only need to reminisce on the extravagance of ministers such as Father Divine, Bishop Charles Manuel

“Sweet Daddy” Grace, or Rev. Frederick Eikerenkoetter (more commonly known as Rev. Ike) and we all know the names

of their contemporary equals. The current state of alarm is due to the fact that prosperity ministries, which

once were rare exceptions within the black church tradition have now become more dominant and visible representations

of our most noble institution.

If the black church tradition is going to counteract the growing imbalance between a Gospel of prosperity and a Gospel for posterity,

serious and thoughtful changes have to take place. On the corporate level, just as each Christian is expected to tithe a portion of

his/her income and talents to God’s work in the world, each and every Church should also tithe a share of its capital—both human and monetary—back

to the community in order to meet the needs of “the least of these” described in Jesus’ parable in Matt. 25: 31-46.

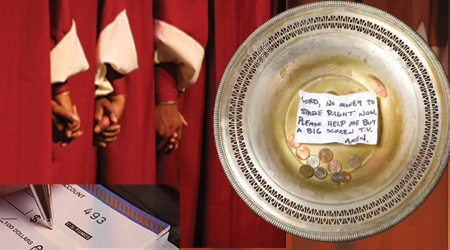

IV. Thoughts on the Movie First Sunday

The recent movie, First Sunday, is an interesting commentary regarding the primacy placed on money within the contemporary African

American experience especially as it pertains to the African American church tradition. The main characters, Durell and LeeJohn, are

lifelong friends strapped for cash due to their own particular financial dilemmas. Facing utter desperation due to their financial woes,

LeeJohn concocts a scheme in which he and Durell would rob the First Hope Church of Baltimore on the first Sunday (hence the film’s title)

in the hopes of hitting the church at the time when they anticipate its coffers to be overflowing with cash. Although clearly concerned

about their safety, the pastor and the church members try to make reasonably compelling pleas to Durell and LeeJohn about why the men

should not to go through with the robbery. The church members fail. However, another problem quickly unfolds: the money Durell and

LeeJohn came to steal is already gone! That’s the gist of the movie.

The fact that this film’s story is about desperate and disaffected young black men whose only reason to enter a church on Sunday is

to rob it, is considered worthy material for comedic treatment, should truly alarm anyone remotely concerned about the black church

tradition both presently and historically. It is my thinking that this element of the story is actually more serious than the

filmmakers and actors realize. Although the church still has centrality within the African American community, there are growing

numbers of young black men who are becoming distant from Christian fellowship because even though they hear a whole lot about

Jesus, they do not have anyone actively showing them where Christ is in the midst of the daily crisis of their lives. In light

of that reality, the characters of Durell and LeeJohn represent two figures who are knowledgeable enough about the church to

know many of its inner workings (what day of the month ought to be a high attendance worship service, how much church members

are supposed to tithe, how to behave upon entering the church, etc.) yet feel completely alienated from its reality.

The fact that the pastor and the various members of the congregation as a whole could not demonstrate a strong enough Christian

witness to convince the potential robbers to quit their flawed and blasphemous plan, poignantly illustrates the uphill battle

facing many churches that try to profess a lovingly moralistic gospel in an increasingly money-dominated, market-driven society.

Finally and importantly, it is bitterly ironic that even when the two criminally minded young men finally enter the church to

carry out their dirty deed of running away with the church’s cash rather than seeking God’s saving grace, Durell and LeeJohn

could not even find that in the house of God! Whether intentionally or not, the movie points out that without either

the spiritual strength of the Holy Ghost to sustain ordinary folks in their everyday struggles of life,

or the material means by which to provide for the ongoing faithful works of the church within the community,

the church is ultimately an empty shell without power to serve as stewards of God’s earth and for our neighbors in need.

V. “First Fruits” Sunday

When thinking about one of the finest exemplifications of stewardship enacted within the historic black churches tradition’s

of liturgy and worship, the celebration of “First Fruits” Sunday come foremost to my mind. Based on the biblical instructions

found in Proverbs 3:9-10, “First Fruits” Sunday is a special church day—typically the first Sunday in November—designated

for offering God your first, and very best, gift as our biblical ancestors once did when they brought forth the choicest

produce from the harvest that God blessed them with during a given year. In modern terms, this sort of sacrificial offering

is largely in terms of money, but the visual representation does have a powerful impact that can never be overlooked.

In the spirit of the occasion, the church is decorated with the colors of the autumn season—gold, rust brown, red,

orange, and occasional splashes of green—to reflect the gloriously resplendent hues associated with the harvest.

In my home church, baskets are filled to overflowing with various produce such as apples, oranges, pomegranates, lemons,

carrots, and various other fruits and vegetables as part of the décor as well as an actual prop in the service. Before

offering time begins, the pastor proceeds to use the array of fruits and vegetables to give a visual indication of what

it means to give a “tenth” of what you have to God. Often the preacher will say something to the effect of, “You mean

to tell me that out of these ten apples right here, God just wants one shiny apple and I get the other nine for me.

Well, since God is the source and provider of the apples in the first place, I think that’s a fair deal.” By repeating this

example with the various fruits and vegetables, the preacher can often use humorous and endearing comments to drive home the key

instruction of this exercise, namely that the tithe is a minor but mandatory tribute to a God that does so much for us.

The chief principles that are represented in the “First Fruits” worship service are:

1. commemoration: remembrance of what God has done on behalf of the

faithful;

2. consecration: giving praise to and proclaiming the goodness of God as

the source of all money and material possessions; and

3. anticipation: awaiting God’s restoration and future blessing.

In many regards, the “First Fruits” worship service is significant because it is a way of reminding the congregation about

its biblical obligations in a way that is not only rooted in the history and heritage of African peoples as being people

of the land, but also tackles a typically thorny issue—talking about monetary donations—in a way that can be amusing,

instructive, and even festive.

VI. Songs for this Calendar Moment

All Things Come of Thee

All things come of thee, O Lord;

and of thine own have we given thee.3

We Give Thee but Thine Own

We give Thee but Thine own,

What e’er the gift may be;

All that we have is Thine alone,

A trust, O Lord, from Thee.

May we Thy bounties thus

As stewards true receive,

And gladly, as Thou blessest us,

To Thee our first fruits give.

Oh, hearts are bruised and dead,

And homes are bare and cold,

And lambs for whom the Shepherd bled

Are straying from the fold.

To comfort and to bless,

To find a balm for woe,

To tend the lone and fatherless

Is angels’ work below.

The captive to release,

To God the lost to bring,

To teach the way of life and peace

It is a Christ-like thing.

And we believe Thy Word,

Though dim our faith may be;

What e’er for Thine we do, O Lord,

We do it unto Thee.4

Notes

- Thomas-Lester, Avis. “Tithing Rewards Both Spiritual and Financial.” Washington Post. 15 Apr. 2006: A01.

- Carlson, Edward. “Do Worshipers Give God His 10 Percent?” Online location:

Beliefnet.com accessed 18 January 2008

- "All Things Come of Thee." Text: I Chronicles 29:14b; Music: Anonymous

- 4. How, William W. “We Give Thee but Thy Own.”

|

| |

|

|

2013 Units

Multimedia

|