|

KWANZAA

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Monday, December 26, 2011–Sunday, January 1, 2012

(View the Kwanzaa PowerPoint presentations below.)

Itihari Toure, Guest Lectionary Cultural Resource Commentator

Director, The Center for Afrikan Biblical Studies at First Afrikan Presbyterian Church, Lithonia, GA

I. The History

Kwanzaa (pronounced Kwon-zah) means first fruits and is a non-religious seven-day celebration created in 1966 in the midst of the Black consciousness movement in the United States. It therefore reflects the activism of that time and the call for cultural unity. In the context from which Kwanzaa emerged, cultural nationalism was predicated upon the belief that there existed among African people globally a particular ethos or way of being that could restore a sense of community and wholeness to a people fragmented and confused by the psychological and sociological conditions of oppression. Kwanzaa was birthed within a cultural nationalist organization called the US organization, founded by Dr. Maulana Karenga. Dr. Karenga had developed a way of thinking about color, consciousness, and culture which he titled Kawaida.1

Before describing the philosophical framework of Kwanzaa, it is important to understand the context in which Kwanzaa developed, which will also explain its influence on African people across the globe. Many of us are familiar with the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s and much of the stereotypical imagery used to describe the militants of this era. It could appear from these stereotypical images of young men and women with Afros dressed in African clothes that the main intent was to return to our original birthplace, the beautiful continent of Africa. Certainly there were groups of Black people on the African continent, in the United States and the African Diaspora with that goal in mind. But more than this there was a movement to instill a sense of pride and recognition of African culture in our people. This movement sought to have Black people position African ways as their center for explaining and interpreting life: they may not have been born in Africa but the movement wanted Africa born in them. By taking on African names, adopting African ceremonies for marriage and births of babies, and learning African traditional dances and languages, Black people in the United States and in the Diaspora generated a sense of agency about what was valuable to Black people.

What was valued came from African ways of being, an African worldview. Dr. Molefi Asante in the 1990s would later frame this African centeredness as Afrocentricism.2 In constructing the tenets of the US organization, Dr. Karenga articulated that being Black was not just the result of skin color but of consciousness, cultural ways of being, as well as the color of one’s skin. It was from this framework that Dr. Karenga created the Nguzo Saba (seven principles) on which Kwanzaa is based. The Nguzo Saba is a value system that elevates seven principles for the revitalization and restoration of African people.3 Of all the cultural expressions that emerged from this era, Kwanzaa became the best model of what people of African descent could practice that reflected a value for African consciousness and African culture. For almost 50 years, Kwanzaa has been the evidence of a purposeful and meaningful practice of unity that fulfills a central need of any people to possess a healthy and positive group identity. Its existence in the global community of African people has transformed it from an expression of cultural nationalism to a tradition in the African world.4 There are tens of thousands who have grown up with Kwanzaa in their homes and in their communities. The symbols and exercises of Kwanzaa practiced in so many different places create a common bond, and at the same time the diversity of where Kwanzaa is celebrated recognizes the unique contributions of African people everywhere.

II. Word Etymology

Kwanzaa is a word based upon the Kiswahili language of East Africa. The word Kwanzaa is derived from the Swahili phrase “matunda ya kwanza,” which means “first fruits.” The Kiswahili word “kwanza” means first. An additional “a” was added to establish the celebration’s name and to align that name with the Nguzo Saba (seven letters and seven principles). Kwanzaa is not a celebration that originated on the African continent. It is a holiday (celebrated December 26 through January 1) that is based upon a common African celebration of the harvest which is found all over Africa. These festivals honor the first fruits of the harvest as a gift from Our Creator and blessing to the community. The idea of the first fruits being special unto God is not unfamiliar to Christians as the Old and New Testament Scripture speak about first fruits.

III. Autobiographical Story

Growing up in Los Angeles in the 1960s placed me right in the middle of the cultural nationalist movement. I had witnessed four high school seniors get expelled from my Catholic High school for wearing their hair in a natural. I wondered what was so important that these young women would risk getting kicked out of school. This began the trajectory of culture and consciousness-raising in my own life. I was invited to attend a Kwanzaa night at the afterschool and Saturday program in which I had been volunteering. What I experienced that night would never leave me. It seemed to be the answer to the mistrust and destructive behaviors I had seen growing up on the streets of Los Angeles and in Compton, California. Kwanzaa made such an impression on me that as the youngest of six children I fearlessly brought it into my family, who still celebrate it today. I have reared three children who have celebrated Kwanzaa since their birth and I attend a church who hosts Kwanzaa community celebrations every year. Kwanzaa is celebrated through rituals, dialogue, narratives, poetry, dancing, singing, drumming and other music, and feasting.

IV. Kwanzaa as a Meaningful Practice of Unity

So what makes Kwanzaa such a meaningful practice of unity? It is in its intent as much as in its structure. Dr. Karenga explained the intent of Kwanzaa to connect five common African ways of being in celebration:

(1) The ingathering of family, friends, and community. There are times when we can recall how good it felt just being around family and friends; somehow whatever was ailing us seemed to be less intense once we all got together. For many of us, gathering became the sign that everything was going to turn out alright; we recognized that strength in coming together. Church house

meetings, Sunday worship, family reunions, even weddings and funerals would somehow

reconnect family and place the challenges we faced in background. We sang the chorus of songs

like “by and by when the morning comes, all the saints of God will be gathering home; we will tell the story how we overcome and we’ll understand it better by and by.” Kwanzaa builds upon

the existing strength in gathering as a community and as a family. Kwanzaa recognizes that

coming together in unity does not restrict nor require anything but the willingness to come

together. In fact, it embraces the belief that there is some anticipation in seeing folks you have not seen recently or making connections to others you did not know.

(2) Reverence for the creator and creation (including thanksgiving and recommitment to respect the environment and heal the world). A Kwanzaa ceremony opens with a welcoming libation. A libation acknowledges all aspects of creation and the one who created all. In the traditional African context, the libation is a prayer for spiritual unity among those who are present, those who are deceased, and those who are yet unborn. The libation creates a circle of unity by acknowledging that all of creation is affected by what each one of us chooses to recognize and to do. The libation uses one of the Kwanzaa artifacts, the unity cup (kikombe cha Umoja in Kiswahili), water, and a live plant. It is used to pour tambiko (libation) to the ancestors in remembrance and honor of those who paved the path down which we walk, and upon whose shoulders we stand, and those who taught us the good and the beautiful in life. With each pouring of the water onto the live plant, there is a call, a prayer that invites and welcomes all of Creation. When I pour libation it is a storytelling moment. It is an opportunity to tell our story from the very beginning of time. The libation aids in reconnecting to the beauty of our past, the resilience of our people, and the hope of life for those to come. By stating out loud: “Now say the names of your own family members who you know helped you to be the person you are today. Name those family members who came before you and who others have told you that you are just like!” After each name you hear we say “Ase,” which means and so it is. And when everyone gathered begins to hear the names being called out, more and more persons remember and call out family members’ names until it feels as if there is no room in the sanctuary because we all feel the presence of our people surrounding us and the power of God.

(3) Commemoration of the past (honoring ancestors, learning lessons, and emulating achievements of Afrikan history). Each symbol of the Kwanzaa table and the presence of African artifacts for aesthetics purposes represent the wealth of African culture and tradition. The Kwanzaa setting with these symbols and artifacts is set up and talked about every night of Kwanzaa. The oral sharing of what each symbol represents imparts to the listener the aspects of our culture and legacy that are most valuable to our wholeness and healing. We cover the Kwanzaa table with colors of red, black, and green. These are the colors adopted by the Garvey Movement as a symbol of the Black nation (established by the United Negro Improvement Association UNIA in 1920). We call these colors our liberation colors and they are most commonly identified as a flag. On the table we place a straw mat called Mkeka in Kiswahili. The mat symbolizes our tradition and history upon which everything else rest. During Kwanzaa we can recall so many persons in our history from whose creativity we have benefitted, such as our early resilient and determined Black inventors. During Kwanzaa this mat or mkeka can also remind us of our collective creativity, resilience, and brilliance, especially if we recall Black townships (Eatonville and Rosewood, Adderlyville, and Fort Mose in Florida; Boley, Brooksville, Clearview, Grayson, Langston, Lima, Red Bird, and others in the Oklahoma Territory). Sharing the history of these townships as well as that of Black organizations paints a picture of community unity. It places in our imagination the possibility of building and sustaining entire communities.

(4) The corn (the Kiswahili word is vibunzi or muhindi) positions our children both biological and communal as valuable assets to our tradition. The connection of children beyond their biological parents reinforces the tradition of the extended family. Some of us recall the stories of children being raised by others not their parent(s) or stories of how everyone on the block had some instruction for you as you were growing up that you dare not ignore. Still today, children in the church I attend are esteemed by the entire congregation. Kwanzaa reinforces extended family unity by relating the role of our children as vital to our legacy and our traditions.

| At the church I attend in Lithonia, Georgia, we have extended this aspect of Kwanzaa by calling all of the children to the front and having one of the elders in the congregation interpret the principle of extended family unity through a story. We call it Elder’s Words of Wisdom and sometimes if comes from a lived experience and other times the story is from a printed medium. Last year, as an elder with this charge I used the African story Seven Spools of Thread: A Kwanzaa Story by Angela Shelf Medearis and Daniel Minter. The story illustrates all of the Kwanzaa principles of unity (Umoja) and Collective Work and Responsibility (Ujima). It describes how sons who did not get along were able to create something beautiful and royal once they decided to work together. What they created was a piece of Kente cloth, so esteemed that it becomes the cloth of the Chief. Seven bright colored spools of yarn and a basket full of woven Kente was part of the storytelling. As children held the single spool, they looked around and realized that there was little to do with just a spool. Just as the boys in the story learned when they decided to get along and put the threads together and created the beautiful fabric, our children were being taught to also unite to produce something beautiful.5 |

|

I used the following PowerPoint presentation on the screen so that the adults in the pew could follow the story as it was read to the children. Feel free to use it in your congregation. It also works well as a children’s sermon. Download Kwanzaa PowerPoint

(5) Recommitment to the highest cultural ideals of the Afrikan community (for example, truth, justice, respect for people and nature, care for the vulnerable, and respect for elders). This aspect of Kwanzaa is the core cultural transmission and source of community healing for African people globally. It is represented by the seven candles and the candleholder itself. The Kiswahili word for candles is Mishumaa and the word for candleholder is Kinara. Dr. Maulana Karenga created Kwanzaa as a way to transmit a set of core values in which he believes and time has confirmed his belief that African people needed to reconstruct a set of values/principles that would serve to guide our living and hasten our progress. The Nguzo Saba (Seven Principles) is represented by each candle being lit, discussed, and illustrated through song, dance, drama, and lecture for each of the seven days of celebration. Kwanzaa is celebrated by over 20 million people around the world, so apparently there is mass agreement with the elevation of these seven principles. They are principles that can be applied to all aspects of life, in all situations, and in different contexts:

- Umoja (unity),

- Kujichagulia (self-determination),

- Ujima (collective work and responsibility),

- Ujamaa (cooperative economics),

- Nia (purpose),

- Kuumba (creativity), and

- Imani (faith).

Each night of Kwanzaa after the libation and welcome, we sing songs that talk about the principles. One of our favorites (sung to the tune of “Amen”) is included below. The candle lighting ceremony also done each night begins by using call and response to say each principle, its Kiswahili name, and its meaning. The colors of Kwanzaa are black, red, and green; black for the people, red for their struggle, and green for the land and the better future that is the result of the struggle. On the Kinara we place one black candle, three red candles, and three green candles. “These are the Mishumaa Saba (the seven candles) and they represent the seven principles. The black candle represents the first principle Umoja (unity) and is placed in the center of the Kinara. The red candles represent the principles of Kujichagulia (self-determination), Ujamaa (cooperative economics), and Kuumba (creativity) and are placed to the left of the black candle. The green candles represent the principles of Ujima (collective work and responsibility), Nia (purpose), and Imani (faith) and are placed to the right of the black candle. The black candle is lit first on the first day of the celebration. And the remaining candles are lit afterwards from left to right on the following days. This procedure is to indicate that the people come first, then the struggle, and then the hope that comes from the struggle.”6

V. Kwanzaa at First Afrikan Presbyterian Church of Lithonia, Georgia

Celebration of the “Good of Life” (for example, life, struggle, achievement, family, community, and culture). The last two symbols of Kwanzaa are the crops (Mazao), a bowl of fruits and vegetables that represent a good harvest and the gifts or Zawaidi that are the result of positive and productive work by the children in the family and community. These artifacts illustrate the blessing of a good life, a good harvest, a year in alignment with the will of Our Creator and operating in the best interest of the collective good. Gift giving at Kwanzaa is not a commercial event. The gifts given are to represent the beauty and wealth of African heritage through the arts, tools to achieve educational excellence (such as books and educational games), or products that result from collective efforts in the family (such as baking sweet edibles or items made by the family such as quilts, carvings, etc.).

Over the past 16 years our church connected the nights of Kwanzaa to a theme that expresses and explains the “good life” African-descended people in the United States have created. The cultural ways (art forms, music, dance, literature) which like the Kwanzaa holiday are rooted in African tradition, yet are reflective of our unique experiences in North America, are interpreted through each night’s principle. Here are examples of actual events and practices that create Memorable Learning Moments during Kwanzaa; they were connected with our annual church themes for Kwanzaa:

|

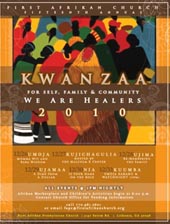

2010—“For Self, Family, and Community: We Are Healers”

The theme recognized African-descended people’s ability to solve our own problems. The residuals of oppression in its many forms did not deter the creative and resilient nature of African people to look within themselves and around their communities for ways to recover, remember, and restore themselves, their families, and their communities. Each night of Kwanzaa we celebrated the ways of African-descended healers. The first night Baba Wit and Mama Wisdom celebrated the home remedies, healing proverbs, and teaching phrases passed down from one generation to the next. Despite laws that limited their access to health care, education, and social advancement, elders in our families taught us how to make medicine and use what we had around us to ward off sickness. On this night we recalled these things and shared with one another the ways of staying strong from taking castor oil to eating beets.

|

|

2009—“Soul Food, Soul Music, Soul People”

The Kwanzaa program book and nightly focus taught the origins of soul food and soul music. We took a stroll through our history to connect the dishes we enjoy with the African continent and even in the Diaspora. We held a cooking contest for the best pot of greens. They warmed our bellies as we walked through the Afrikan marketplace set up in our community room. The elders brought out actual record albums for the children to see and pass around. They were amazed that music came from these huge black circles. The elder shared melodies from a time when African Americans started their own record labels such as STAX, Checkers, and of course Motown.

|

|

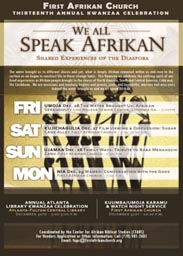

2008—“We All Speak Afrikan: Shared Experiences of the Diaspora”

This Kwanzaa celebration recognized the unity and relatedness of African people of the Diaspora. “Passages: The Water Brought Us” by Mausiki Scales and the Common Ground Collective was the theme music which aided us in being transported through the Caribbean and South America. The film Sugar Cane Alley and the discussion that followed the film enlightened viewers on the similarities of the realities of African people in the United States and in the Caribbean when it came to systemic efforts to denigrate the cultural ways of indigenous people and those Africans brought to here on slave ships. |

|

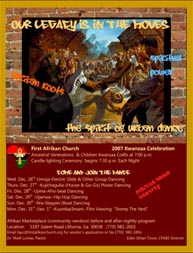

2007—“Our Legacy Is in the Moves…The Spirit of Urban Dance”

Contemporary dance created in our communities reflects the power and presence of Afrikan culture. Not only do our dance moves reflect the movements of traditional Afrikan dance, our urban dance invokes the power of Spirit that has been a source of creativity, strength, and determination for Afrikan people. What better way to illustrate the seven principles of Kwanzaa than to celebrate Afrikan genius, creativity, power, and unity through our urban dance. Each principle of Kwanzaa was expressed through live dancing and commentary connecting our urban “Kuumba” to our Afrikan cultural dances. |

You can develop your own poetry readings, songs, dances, music, and dramatizations as moments of inspiration for these themes and others. The diverse interpretations of our ways of being gave room for every talent across age groups in the community to express what was meaningful to them in the context of each Kwanzaa theme. Our program books included resources about Kwanzaa and the aspects of the African Diaspora experience to educate all in attendance about the incredible richness of our culture. We also used film The Black Candle7 by Molefi Asante’s son, M.K. Asante Jr. It is an excellent visual introduction to Kwanzaa. It begins by asking everyday Black folks what they have heard about Kwanzaa and has Maya Angelou and other notables sharing artistic expressions about Kwanzaa and the love and unity expressed through this holiday. The film also provides an overview of Kwanzaa and how it is celebrated.

The closing ritual of Kwanzaa each night was Harambee which means “let’s all pull together.” The Harambee fist is thrown into the air seven times and the last thrust is held and shouted for as long as everyone can. It is the closing act of strength in numbers and in possessing common ideals as presented throughout the entire Kwanzaa ceremony. When we unite, we are strengthened.

VI. Songs That Speak to the Moment

The Kwanzaa principle of Creativity (Kuumba) reinforces the symbols and principles of Kwanzaa as common expressions of African people especially in the United States. During the 1970s many educators working in cultural Saturday programs took everyday songs and turned them into heritage praise songs. During our 2010 Kwanzaa services to elevate the unity in the community through institution building, we took a song common to the Black Christian tradition and used it as a rallying call for Black organizations. We showed the logo for each organization and asked members to stand if they were a part of any of the organizations we called out. By the end of the song, everyone is the room was standing. What a powerful image it was for all the children to see that we all belonged to something more than our immediate families. Download Kwanzaa PowerPoint

Sign Me Up! (To the tune of Sign Me Up for the Christian Jubilee)

Sign me up for the N.A.A.C.P.,

Write my name on the roll

I’ve been changed, since the Lord selected me,

I wanna be ready when Freedom comes.

Sign me up for the S.C.L.C.,

Write my name on the roll

I’ve been changed, since the Lord selected me,

I wanna be ready when Freedom comes.

Sign me up for a Fraternity or Sorority,

Write my name on the roll

I’ve been changed, since the Lord selected me,

I wanna be ready when Freedom comes.

Sign me up for the Order of Free Masonry,

Write my name on the roll

I’ve been changed, since the Lord selected me,

I wanna be ready when Freedom comes.

Sign me up for the Neighborhood Watch,

Write my name on the roll

I’ve been changed, since the Lord selected me,

I wanna be ready when Freedom comes.

Sign me up for the N.A.B.S.W,

Write my name on the roll

I’ve been changed, since the Lord selected me,

I wanna be ready when Freedom comes.

Sign me up for Black Liberation,

Write my name on the roll

I’ve been changed, since the Lord selected me,

I wanna be ready when Freedom comes.

Sign me up for the Military,

Write my name on the roll

I’ve been changed, since the Lord selected me,

I wanna be ready when Freedom comes.

Sign me up for N’COBRA,

Write my name on the roll

I’ve been changed, since the Lord selected me,

I wanna be ready when Freedom comes.

Sign me up for Civil Rights Marching,

Write my name on the roll

I’ve been changed, since the Lord selected me,

I wanna be ready when Freedom comes.

Sign me up for the Order of Eastern Star,

Write my name on the roll

I’ve been changed, since the Lord selected me,

I wanna be ready when Freedom comes.

Sign me up for the P.T.S.A.,

Write my name on the roll

I’ve been changed, since the Lord selected me,

I wanna be ready when Freedom comes.

Sign me up for the Republic of New Afrika,

Write my name on the roll

I’ve been changed, since the Lord selected me,

I wanna be ready when Freedom comes.

Sign me up for African Unity,

Write my name on the roll

I’ve been changed, since the Lord selected me,

I wanna be ready when Freedom comes.

Sign me up for the Black Belt Initiative,

Write my name on the roll

I’ve been changed, since the Lord selected me,

I wanna be ready when Freedom comes.

Sign me up for the United Negro College Fund,

Write my name on the roll

I’ve been changed, since the Lord selected me,

I wanna be ready when Freedom comes.

Sign me up for the Black United Front,

Write my name on the roll

I’ve been changed, since the Lord selected me,

I wanna be ready when Freedom comes.

Sign me up for the W.A.D.U.,

Write my name on the roll

I’ve been changed, since the Lord selected me,

I wanna be ready when Freedom comes.

Earlier I briefly discussed songs about the principles of Kwanzaa. This version of the familiar tune “Amen” connects the names of the seven principles of Kwanzaa and briefly defines each principle. The repetition of the word Kwanzaa reduces a common anxiety about unfamiliar terms and for some the negative association made when a Kwanzaa ceremony is held in a Black Christian church.

(To the tune of “Amen”)

Strivin’ for Umoja

Kwanzaa.

Unity in our family

Kwanzaa.

Unity in our nation

Kwanzaa, Kwanzaa, Kwanzaa

Kujichagulia

Kwanzaa.

Self-determination

Kwanzaa.

Speaking for ourselves

Kwanzaa, Kwanzaa, Kwanzaa

That’s Ujima

Kwanzaa.

Working together

Kwanzaa.

Building up our nation

Kwanzaa, Kwanzaa, Kwanzaa

Ujamaa

Kwanzaa.

Cooperative economics

Kwanzaa.

Sharing Our Wealth

Kwanzaa, Kwanzaa, Kwanzaa

A little Kuumba

Kwanzaa.

Leaving our community

Kwanzaa.

Better than we found it

Kwanzaa. Kwanzaa, Kwanzaa

Nia is purpose

Kwanzaa.

Purpose for lives

Kwanzaa.

Purpose in our struggle

Kwanzaa. Kwanzaa, Kwanzaa

Imani means faith

Kwanzaa.

Faith in our selves

Kwanzaa.

Faith in our God

Kwanzaa. Kwanzaa, Kwanzaa

The call and response nature of the next Kwanzaa song increases familiarity with African terms in a familiar format:

The Principles of Kwanzaa

I said Umoja, (repeat each line)

It means Unity

Kujichagulia,

Self-Determination

Ujima Means Collective Work and

responsibility

U-Ja-Ma-a

Cooperative Economics

Nia-

Is Purpose

Ku-umba

Creativity

Imani

Is Faith

In What?

Our Blackness

Faith In Our Blackness

Faith In our Blackness

I Said, Kwanzaa!!!

Since Kwanzaa has long been taught in the schools before the school winter break, there are several songs that have been written to familiar childhood tunes such as the song, “The 7 Days of Kwanzaa” (sung to the tune of the twelve days of Christmas):

The 7 Days of Kwanzaa

On the first day of Kwanzaa, my family gave to me,

a cup for our family unity

On the second day of Kwanzaa, my family gave to me,

two woven mats and a cup for our family unity

On the third day of Kwanzaa, my family gave to me,

three special flags and a cup for our family unity

On the fourth day of Kwanzaa, my family gave to me,

four kinds of fruit and a cup for our family unity

On the fifth day of Kwanzaa, my family gave to me,

five ears of corn and a cup for our family unity

On the sixth day of Kwanzaa, my family gave to me,

six handmade gifts and a cup for our family unity

On the seventh day of Kwanzaa, my family gave to me,

seven Kinara candles and a cup for our family unity

VII. Kwanzaa Resources

Books and Articles

- Copage, Eric. Kwanzaa: An African-American Celebration of Culture and Cooking. New York, NY: Harper Collins, 1991.

- Riley, Dorothy Winbush. The Complete Kwanzaa: Celebrating our Cultural Harvest. Edison, NJ: Castle Books, 2002.

- Broussard, Antoinette. African American Holiday Traditions: Celebrating with Passion, Style, and Grace. Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press, 2000.

- Karenga, Ron. “Black Cultural Nationalism.” Chicago, IL: Negro Digest 1968 13(3): 5–9.

Notes

1. Karenga, Maulana. “Kawaida and Its Critics: A Sociohistorical Analysis.” Journal of Black Studies 1977 (8): 125–148.

2. For more information on Afrocentricism, visit: http://www.asante.net/articles/1/afrocentricity/

3. Karenga, Maulana and Tiamoyo Karenga, “The Nguzo Saba and the Black Family: Principles and Practices of Well-Being and Flourishing.” Black Families, 4th Ed, Harriet Pipes McAdoo, (ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2007, 7–28.

4. Pleck, Elizabeth. “Kwanzaa: The Making of a Black Nationalist Tradition.” Journal of American Ethnic History 20 (Summer 2001): 3–28.

5. This story as well as other Kwanzaa books can be purchased online from Amazon Books, Barnes and Noble, and other major book sellers. Seven Spools of Thread: A Kwanzaa Story also has an interactive website at the educational publisher McGraw Hill:

http://treasures.macmillanmh.com/florida/students/grade3/book2/unit4/seven-spools-of-thread.

6. Taken from a great online resource: http://www.africawithin.com/kwanzaa/kwanzaa_celebration.htm accessed 6 June 2011. The best source for the explanation of each principle is Dr. Maulana Karenga’s official Kwanzaa website: http://www.officialkwanzaawebsite.org/7principles.shtml.

7. Asante, M.K. Jr. The Black Candle. Asante Filmworx, 2009. Online location: http://theblackcandle.com/

|