|

THIRD SUNDAY OF ADVENT

CULTURAL RESOURCES

(From the Book of Common Worship)

Sunday, December 12, 2010

Allen Dwight Callahan, Guest Lectionary Cultural Resource Commentator

Independent Scholar, Roxbury, MA

I. The History Section

Mary’s response in Luke 1:47 is traditionally called the “Magnificat,” so named for the first word of the verse in the Latin Vulgate: magnificat anima mea Dominum, “my soul magnifies the Lord.” It is the subversive libretto of a canticle in the Catholic office of “Vespers,” in the Anglican “Evensong” and in the magisterial oratorios of Monteverdi, Bach, Vivaldi, Rachmaninoff and John Rutter. It is the provocative strophe for centuries of Christian hymnody; too restive to remain in Advent, Mary’s irrepressible song erupts under the rubrics of “Praise,” “Justice,” and “New Creation” in modern hymnals. It is the anthem of Latin American Liberation theologians and a popular prayer often carried as an amulet by Nicaraguan peasants.

It is, first, last, and always, a song of praise. Nestled in the Lukan narrative between the angel Gabriel’s “Ave Maria” and Zachariah’s “Benedictus” (“Blessed be,” Luke 1: 68-79), and with the aged Simeon’s “Nunc Dimittus” (“Lord, now lettest thou,” Luke 2:29-32), it is the first of three songs of praise to the God who is Savior (1:47), who has promised to save (1:71), and whose salvation has been made manifest (2:30).

Praise keeps our heads up. And with our heads up, we can look both ways in time. We look ahead, gazing upon the distant horizon of hope. But there is also that backward glance. Biblical praise springs forth from a kernel of the usable past, from history as the record of proof positive that God will save us again, because God has saved us before; that God will be good – to us, for us, in us, and through us – because God has been so.

The Magnificat tells us about God. It tells us about God’s goodness: to sing of the goodness of God is praise by another name. But “the Magnificat is also important,” Renita Weems has reminded us, “because of what it tells us about Mary.”1

A song of call and response, Mary’s song is the lyrical response to the angel’s call of prophecy and to God’s impossible possibility: that God would announce grace in the very face of disgrace. And in the shadow of death – a very real possibility for this lone young woman who appears to have committed what was a capital offense in her time and place. Several centuries after Mary’s canticle had been published in the New Testament, the Talmud described the traditional Jewish penalties for pregnancy out of wedlock: depending upon the attendant circumstances of the offense, she was to be stoned, strangled to death (Kethuboth 44b-45a), or burned alive (Sanhedrin 9:1).

II. Songs that Speak to the Moment

African American theologian Henry Hugh Proctor observed in his Yale dissertation of 1894 that the Negro Spirituals were devoid of Marian devotion. Veneration for Mary appears to be wanting in the Protestant Evangelical sensibility of the Negro Spirituals, even those that were apparently sung in the overwhelmingly Catholic parishes of Louisiana. The mother of Jesus in the Negro Spirituals is not the Mary of “Ave Maria”: she is the grieving matron of the Pieta, the suffering mother of the suffering Jesus. For African American Christianity, the “Sorrows of Mary” are signified and summarized in the lament of the Negro spiritual “Cry Holy”: “O Mary was a woman, and she had a son/and the Jews and the Romans had him hung.”

Cry Holy

Cry holy, holy!

Look at de people dat is born of God.

And I run down de valley, and I run down to pray,

Says, look at de people dat is born of God.

When I get dar, Cappen Satan was dar,

Says, look at, and see.

Says, young man, young man, dere's no use for pray,

Says, look at, and see.

For Jesus is dead, and God gone away,

Says, look at, and see.

And I made him out a liar and I went my way,

Says, look at, and see.

Sing holy, holy!

O, Mary was a woman, and he had a one Son,

Says, look at, and see.

And de Jews and de Romans had him hung,

Says, look at, and see.

Cry holy, holy!

And I tell you, sinner, you had better had pray,

Says, look at, and see.

For hell is a dark and dismal place,

Says, look at, and see.

And I tell you, sinner, and I wouldn't go dar!

Says, look at, and see.

Cry holy, holy!2

In contemporary gospel music, Mary tends to receive prophecy but not proclaim it. Helen Baylor’s “Mary Did You Know?” is emblematic:

Mary Did You Know?

Mary did you know

That you baby boy would one day walk on water.

Mary did you know

That your baby boy will save our sons and daughters

Did you know that your baby boy has come to make you new?

This child that you delivered will soon deliver you.3

Songs in Mary’s courageous, prophetic voice are quite rare.

III. Cultural Response to Significant Aspects of the Text

Sunday, December 12, is a mere two weeks before Christmas. The orgy of conspicuous consumption and compulsive shopping starts just after Thanksgiving. Between the Thanksgiving dinner that millions of Americans don’t have and the Christmas dinner that millions are condemned to do without, the economy will transact seventy percent of its annual retail business. Millions will buy what some want, none need, and few can afford, often with money they do not have, accruing Christmastide debt they cannot pay.

And yet, Advent is the celebration of a poor, unwed mother’s positive pregnancy test. It is an affirmation that God has filled her and those like her “with good things,” and an ominous warning to those rich enough to conspicuously consume and compulsively shop that God “has sent them away empty” (Luke 1:53). Perhaps this is why, in this frenetic season of entitled materialism, we hear few strains of the Magnificat at the Mall.

IV. Audio Visual Aids

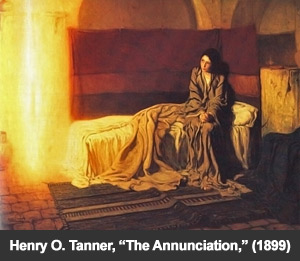

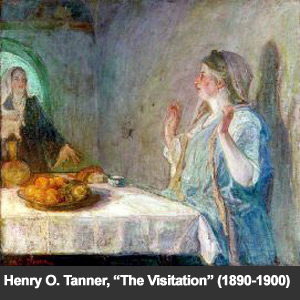

The backdrop of Henry Ossawa Tanner’s “Annunciation” is neither the cathedral of medieval paintings nor the comfortable domesticity of the burgher’s anteroom so much the rage after the Renaissance, but a dimly lit first-century Palestinian shotgun shack. Tanner has given us, with the vigor and spiritual intensity that mark his work, the Annunciation and the Visitation, the angel’s song and Elizabeth’s. But he has not given us the Magnificat. He could have, as did his French contemporary James Jacques Joseph Tissot. Tissot’s “Anunciation” (1886-96) is a departure from medieval and Renaissance interpretations, but it is not the radical break with anthropomorphism that we find in Tanner’s painting: Tissot’s angel, who radiates long needles of light, at least has hands and a face. Tanner’s angel, neither chubby waif nor somber androgyne, is a luminous column at the far left of the scene, shining, yet outshone by his own reflected glare in the face of Mary.

But Tissot gives us the Magnificat – and Tanner does not. It is not what Tanner painted, remarkable as his paintings are, that is remarkable here: it is what he did not paint. This is not an argument from silence; more dubious still, it is an argument from absence: it would seem that Tanner avoided the more provocative scenes of Scripture. He chose to paint “The Flight into Egypt” (1899), but not the Slaughter of the Innocents; “Jesus Visiting Nicodemus” (1899), but not the Cleansing of the Temple; Jesus en route to a Judean suburb just before his fateful last days in Jerusalem in “Jesus and His Disciples on the Bethany Road” (1905), but not the raucous Triumphal Entry. The closest Tanner brings us to Jesus’ Passion is his “Return from the Crucifixion” (1936). And here, too, in his scenes of Advent, Tanner has tacitly refused to bring us to the moment in which Mary sings a song so indelicately incendiary that right-wing Latin American regimes publicly banned it in the 1970s and 1980s.

V. Stories and Illustrations

The birth of the Christ child is announced to his poor, young, unwed mother. And in the Magnificat she responds with acceptance and joy in the face of the dismal prospects for her child by the world’s lights. What chance could such a child have, born with such disadvantages?

Yet it has been our collective experience that the determined mother-to-be can prevail against all the naysayers and the dire prognostications. Maya Angelou chronicles her life up to age sixteen in I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, and ends her autobiographical account with the birth of her son out of wedlock. On the way to that event, the protagonist suffered poverty, abuse, rape, desperation and desertion. And yet she rises; Angelou overcomes crushing adversity to become a writer and public intellectual of international renown. Her child, Guy Johnson, would go on to be the author of two novels: the critically acclaimed debut Standing at the Scratch Line (1998) and Echoes of a Distant Summer (2002).

In 1941, Helen Burns, an unwed teenage mother and the daughter of an unwed teenage mother, gave birth to a son in Greenville, South Carolina. The child’s biological father was one of Greenville’s most prosperous citizens, yet mother and child lived on the other side of the tracks in poverty and obscurity. Though spurned and stigmatized, the boy would grow up to be a star football quarterback, Baptist minister, Civil rights leader, politician, and international diplomat. His name: Jesse Louis Jackson.

And on January 29, 1954, a child was born female, black, and poor in the teeth of Jim Crow in Kosciusko, Mississippi. Her mother, an eighteen-year-old housemaid, and her father, a twenty-year-old doing duty in the armed forces, were never to wed. For the first six years of her life, the young child was raised on a Mississippi farm by her grandmother, who began to tell her that she was “gifted,” that she was a special child. And indeed Oprah Winfrey was a special child.

And so we may still sing Mary’s song, because time and again God is shown to have “exalted those of low degree” and “filled the hungry with good things” (Luke 1:52-53).

VI. Making It a Memorable Learning Moment

Books for the Advent Season

Terrien, Samuel. The Magnificat: Musicians as Biblical Interpreters. New York, NY: Paulist Press, 1995.

Pelikan, Jaroslav. Mary Through the Centuries. New Haven, CT: Yale, 1996.

Notes

1. Weems, Renita J. Showing Mary: How Women Can Share Prayers, Wisdom, and the Blessings of God. New York, NY: Warner, 2002. p. 190.

2. “Cry Holy.” Negro Spiritual

3. “Mary Did You Know?” Helen Baylor. Nashville, TN: Word Music/Rufus Music, 1999.

|