|

Sample 11 Days Plan for an Ecumenical Celebration

ECUMENICAL DAY OF WORSHIP

(DIFFERENT FAITH COMMUNITIES WORSHIPING TOGETHER)

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Sunday, August 30, 2009

Meri-li Douglas, Guest Cultural Resource Commentator and

Bernice Johnson Reagon, Lectionary Cultural Resource Team Commentator

Micah 4:3-4

3 He will judge between many peoples

and will settle disputes for strong nations far and wide.

They will beat their swords into plowshares

and their spears into pruning hooks.

Nation will not take up sword against nation,

nor will they train for war anymore.

4 Every man will sit under his own vine

and under his own fig tree,

and no one will make them afraid,

for the LORD Almighty has spoken.

I. Introduction: A Song for this Moment on the Lectionary Calendar

Gonna Lay Down My Sword and Shield

Gonna lay down my sword and shield

Down by the riverside

Down by the riverside

Down by the riverside

Gonna lay down my sword and shield.

Down by the riverside

Ain't gonna study war no more.

Chorus: I ain't gonna study war no more.

I ain't gonna study war no more,

Study war no more.

I ain't gonna study war no more,

I ain't gonna study war no more,

Study war no more.

Other lines:

I’m gonna lay down my burden…

Gonna stick my sword in the golden sand…

Gonna put on my long white robe…

Gonna put on my starry crown…

Contemporary lines:

Going to lay down the bombs and guns…

Going to join hands the whole world round…1

II. Etymology and Historical Notes

Ecumenism (ecumenical) is based on the Greek word “oikoumene” from its Greek root oikos meaning both “house” and “world.” Early Christians used the word “oikoumene” when referring to the One Church, that is, all Christian communities throughout the known world.2 Over the centuries, the Church expanded into vastly and distinctively diverse cultural milieus and geographical locations. For eleven centuries, all these diverse communities remained bonded by two things: 1) the baptismal acceptance of a common calling to Christian discipleship; and 2) the single biblical origin when all were “of one accord” on the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:1-21).

Early Christian leaders held regularly scheduled church council meetings. Until the eleventh century, these gatherings were held to celebrate the One Church, the One Body of Christ. It was also the time when church leaders addressed practical issues: to articulate scriptural interpretations, to draft creedal statements, and to determine a process for structuring itself as a single social institution. As the church expanded geographically, the increasingly diverse cultural and social norms created schisms of theological understandings and faith expressions that became impossible to reconcile.3

In the year 1054, the seventh such council was held, and it was there that the Church experienced its first division and the formation of the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church.4 It was a pattern of institutional divisions that would repeat itself hundreds of times throughout history, representing substantial and distinctly differing interpretations of Christian discipleship. The ecumenical movements of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have been challenging Christians to re-establish the unity of Christ and to celebrate the Church’s rich diversity.

This long sought unity is not a call for uniformity but unity as the One Body of Christ. Ecumenism is a challenge to all who would declare Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior to celebrate common biblical and historical groundings which are the common origins for all Christians of all configurations throughout the world and all of history.

III. Black Ecumenism

Mary R. Sawyer’s 1994 publication, Black Ecumenism: Implementing the Demands of Justice, is a comprehensive study of the history of interdenominational efforts among African American churches to confront social injustices within this country. Sawyer defines and provides an in-depth analysis of black ecumenism and the ways in which it differs from other ecumenical activities within the larger Christian church community. She identifies the common history of slavery from which African American churches have emerged as providing an inherently effective capacity to cooperatively witness for justice in the context of faithful living.

Many white Christians during this period of American history failed to see the idolatry of manipulating the sacred scriptures to justify the unparalleled brutality of slavery. Yet, many of the victims of slavery found within the gospel a message of liberation that nurtured and embraced their humanity and offered spiritual wholeness. The social systems of evil designed by misguided Christians made it necessary for African American slaves to separate themselves from White Christendom in order to experience the redeeming grace of Jesus Christ.5

What is the task of black ecumenism? Sawyer offers this answer:

The objective of black ecumenism, unlike that of white ecumenical movements, is neither structural unity nor doctrinal consensus; rather it is the bringing together of the manifold resources of the black church to address the circumstances of African Americans as an oppressed people. It is mission oriented, emphasizing black development and liberation; it is directed toward securing a position of strength and self-sufficiency.6

A traditional African American church song says:

When all God’s children get together

What a time, what a time, what a time

We’re gonna sit on the banks of the river

What a time what a time what a time.

Historically, the black church has been the manifestation of saving grace for African Americans. In many practical ways, the church united black people into a bulwark against a mighty unrelenting storm of injustice. That sense of unity continues today, whether that conviction of liberation is within African American denominations or among those African American congregations existing as enclaves within predominately white denominations. Throughout the years, the agenda for the black church has been multi-dimensional: to introduce and nurture the concept of the soul, that within that was eternal, to educate and empower their young, and to address the social and ethical injustices that levy an unyielding barrage of discrepancies in employment, housing, and health care.

African American participation in ecumenical efforts engineered by predominately white denominations have often overwhelmed, and perhaps on occasion devalued, the African American religious experience. In his study, Social Teachings of the Black Church, Peter Paris notes that when black churches join forces, their agenda is more likely to reflect the ideal of equal among equals based on the oneness of a “shared ethical principle of racial liberation, which in turn derives from the principle of the parenthood of God and the kinship of all people.”7

Thus, historically, it has not been a question of theological debates because such efforts did not address those social justice issues that were more compelling for African American communities. Capitalizing on the oneness that comes from a common history and cultural context simply makes ecumenical efforts among African American churches more “do-able.”

IV. Ecumenical Interfaith Services

In contemporary expressions, Ecumenical services have featured shared observances not only across Christian denominations but also across faiths communities. These services reach beyond Christian family and provide an opportunity for the coming together to share that which is resonant with respect and acknowledgement of a world big enough for different ways of communal life journeying.

November 19, 2006, hosted by the Capitol Hill Seventh Day Adventist Church in Washington, DC, members from faith groups gathered in an Ecumenical Interfaith Service of Thanksgiving. Participating were Seventh Day Adventists, Buddhists, Lutherans, Episcopalians, Hebrews, Catholics, the Unity Church, Church of the Brethren, and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. The planning committee for the service had representation from all of the participating faith communities.8 The actual service was amazing in its embrace. There were three choral preludes, performed by three musicians; the candle lighting litany was voiced by Muslim, Buddhist, Methodist, and Hebrew liturgists. And Michele Riley Jones, the host church musician and African American lectionary liturgist, led those gathered in this congregational song:

This Is the Day

This is the day, this is the day

That the Lord has made, that the Lord has made.

We will rejoice, we will rejoice

And be glad in it, and be glad in it.

This is the day that the Lord had made,

We will rejoice and be glad in it.

This is the day, this is the day, that the Lord has made.9

V. The National Council of Churches Showing What Ecumenism Can Do

They Will Know We Are Christians by Our Love (We Are One in the Spirit)

We are one in the Spirit. We are one in the Lord.

We are one in the Spirit. We are one in the Lord.

And we pray that all unity may one day be restored.

Refrain:

And they’ll know we are Christians by our love, by our love.

Yes, they’ll know we are Christians by our love.

We will walk with each other. We will walk hand in hand. (Repeat)

And together we will spread the news that God is in our land.

We will work with each other. We will work side by side. (Repeat)

And we’ll guard each one’s dignity and save each one’s pride.

All praise to our God from whom all things come. (Repeat)

And all praise to Christ Jesus who makes us one.10

Since its founding in 1950, the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA has been the leading force for ecumenical cooperation among Christians. The NCC’s member faith groups come from a wide spectrum of Protestant, Anglican, Orthodox, Evangelical, historically African American and Living Peace Churches and include 45 million people in more than one hundred local congregations across the nation.11

NCC, the Ecumenical Minority Bail Bond Fund, and the Dawson Five

The Ecumenical Minority Bail Bond Fund (EMBBF) was established by the pooling of funds by NCC member denominations to purchase treasury notes, which were used as bail for people of color who were subjected to political harassment or whose cases represented bail abuse or other circumstances that denied defendants their rights. Upon completion of a defendant’s trial, the treasury notes would be returned to the fund. The call to create such a fund was made by Native American activists and spiritual leaders, and theologians and administrators from mainline Christian churches attending the Native American Consultation with the Churches. The consultation, which was likely the first such gathering of its kind, was organized by the Interreligious Foundation for Community Organization (IFCO) in 1975, which played a key role in the fund’s implementation. IFCO was established in 1967 (Reverend Lucius Walker, Jr., founding executive director) as the first national ecumenical foundation primarily committed to the support of community organizing. At the time of the creation of the Ecumenical Minority Bail Bond Fund, IFCO was a project inside of the NCC, and inside and outside of that structure, IFCO acted as a bridge between predominantly mainline churches and community groups conceived of and run by people of color. It acted “as a broker for the channeling of interdenominational support, and as a resource bank supporting the work of congregations and organizations engaged in community-building.”12

In the following account, Adisa Douglas, the NCC/IFCO staff member who physically transported the bond, relates this account which demonstrates the point that sometimes ecumenical work is cutting edge and dangerous work:

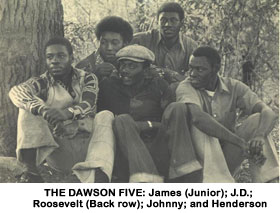

Two years after the inauguration of the Fund, it was effective in securing bail for the young members of the Dawson Five case. The five black youth who made up the Dawson Five were Roosevelt, 17, his brother Henderson, 21, their cousin J.D. Davenport, 18, James Jackson, Jr., 17 and his brother, Johnny, 18. They were arrested in 1976 and indicted on charges of armed robbery and first-degree murder of a white farmer who was a customer at a small country store. They were indicted despite the fact that the five young men had been seen by neighbors at the time of the crime one and a half miles from the armed robbery, despite the fact that no weapon or useful fingerprints were found, and despite a shaky eye-witness story. As part of the indictment, the state made it clear that, if convicted, the youth would be given the death penalty.

My whole body shook as I drove my rental car down the two-lane Georgia, country road. I thought, “Those guys are following me!” I tried to speed up, but the next thing I knew the car with the two white men tailing me was coming up on the left side of my car, trying to push me off the road. As I swerved to the right, the car sped passed me, a hazy image in the soft diffused light of early evening and in my moment of absolute fright. Now aware that they had gone and were probably not turning around, I was one grateful woman.

It was a hot August day in Dawson, Georgia in 1977. I had just left the home of Mrs. Fannie Lou Watson, the mother of Roosevelt Watson, one of the five young defendants of the Dawson Five, a case that became a cause célèbre because of its blatant injustice and racism. The case created national outrage when it became clear that it included coerced confessions, including the one from Roosevelt who later said:

They told me the sheriff wanted to see me. They took my hand prints. They asked me about it. I told them I didn’t do it. They told me they gonna put me in the electric chair, gonna put me in prison all my life. They had these two things hooked to my fingers. Had a thing on my arm, real tight. Said they gonna electrocute me if I didn’t tell ‘em.

The pro bono attorney of these five young men was Millard Farmer, the brilliant, internationally known trial lawyer of the Atlanta-based Team Defense, a legal project of the Southern Poverty Law Center, which did mass mailings and fundraising for the case.

On that hot August day, Millard and I had just finished visiting with Mrs. Watson, her son, and James (Junior) Jackson, of the Dawson Five at the end of the first day of the pre-trial hearings. Millard had headed out in his car, and I left a bit later, getting turned around as I tried to follow him. I figured the two white men in the car knew I was the black woman who had been in the courtroom earlier that day, the woman from the National Council of Churches, which was responsible for posting part of the bail for members of The Dawson Five. In addition to wanting to chase this black outsider out of town, the white men were no doubt angry about William Rucker’s stunning testimony at the trial. Rucker, white, a former Dawson policeman and the defense’s principal witness, broke all the rules of old south white law enforcement and testified that he had been present when a Terrell County sheriff’s deputy put a pistol to the head of one of the defendants, James Jackson, Jr. 18 cocked it, called him a “nigger” and ordered him to find the murder weapon. To a stunned courtroom, Rucker also testified that he saw and knew about other threats and coercion as well used to obtain the confessions.13

On December 19, 1977, less than four months after the pre-trial hearing, the Dawson Five were freed. These five black teenagers, whose families were poor, were kept for periods ranging from nine months to nineteen months in the Terrell County Jail awaiting trial or waiting to be released on bond, which was $100,000 for each young man. Although finally free, these five young men suffered a terrible injustice.

The bail funds that enabled some of the Dawson Five to get out of jail before the pre-trial hearing came from several sources, and as each bail was raised, the five youth met in jail and collectively decided who would be released with each bond, with only Roosevelt and James Jackson being released. They decided that Roosevelt should go first since he was pegged as having fired the trigger that killed the white customer and was the most vulnerable and that James would go next since he was the youngest. Roosevelt’s bail was insured by an Atlanta resident, who signed a bond based on the $125,000 value of her home. James Jackson, Jr. was released with $50,000 raised by individual contributions to Team Defense and $50,000 from the Ecumenical Minority Bail Bond Fund (EMBBF) of the National Council of Churches (NCC), which I staffed with the Reverends Jim West, Ricardo Potter, and Joan Martin.

VI. Reverend Meri-li Douglas: An Ecumenical Lesson

Several years ago, I served as Presbyterian Campus Minister at a historically African American university in North Carolina. Like all colleges and universities, the administration takes a survey of its incoming first year students to create a profile of that class. I took an active role in collecting and analyzing the data. It was no surprise that the largest percentage of students were from poor and blue collar working families in rural communities. One question on the survey asked students to identify any religious affiliation. Most responses were “Baptist,” “non-denominational,” or “other” –a fairly accurate accounting of African American religious expression in the state. So it was also no surprise that only three students identified themselves as Presbyterian.

I quickly learned that students attracted to campus ministry were from strong Pentecostal, evangelical church communities. At my first gathering of students (as it happened, all freshmen), I asked them to introduce themselves and say what church they attended back home. I expected them to say they were Baptist or that their local church was non-denominational. The twelve students in the room began to express confusion about the word “denomination.” It became clear to me that they were unaware of any connection their local congregation had with any larger organized religious institution. As one flustered student told the group: “My family and I go to … (here she gave a rather long name that included words such as “apostolic,” “free” and “Word of God”) Church. It’s a Christian Church! That’s all. We never call it anything else.”

Most had never heard of Presbyterians. They were surprised to learn that, in order to become an ordained Presbyterian minister, I had to attend graduate school, meet rather rigorous academic standards, and demonstrate biblical and theological knowledge well beyond bible stories and identifying specific Bible verses on demand.

While they found my faith journey rather curious, I found theirs equally intriguing and learned much from them as they shared their understanding of Christianity and discipleship. On the one hand, for them it was a “stand alone” faith. These young adults had been given a faith firmly anchored in a strictly structured Christian standard of morality. I came to honor their faith and the way it grounded them with a palatable sense of power and sustenance. They had accepted those standards as spiritually sustaining, and their families had sent them off to college with admonitions to remain faithful. It was my role to challenge and affirm their faith journeys.

At this first encounter, I had been offered a very special opportunity to both confirm their faith and have it nurtured by a Christian expression vastly different from their own. Most of those gathered did not understand that their independent church belonged to or was a component of the Church universal. I set aside the program I had planned for the group and used the opportunity to introduce them to the idea of a Universal Church and the spectrum of expression it represents.

Over the years, I have reflected on this experience. It offers particular insight as I consider Christian ecumenism, because meaningful ecumenical activities best serve those in the pews. Ecumenical services heighten the awareness of the practical realities that shape and inform day-to-day Christian experiences for those who are not formally theologically trained believers. Effective ecumenism enhances the dialogue between scripture and reality and any discussions, documents, or social actions must engage many, many diverse realities.

Notes

1. “Gonna Lay Down My Sword and Shield.” (Down by the Riverside.) Traditional.

2. “Ecumenical.” Online Etyomology Dictionary. Online location: http://www.etymonline.com accessed 19 March 2009

3. The Internet Medievel Source Book. Online location: www.Fordham.edu/halsall/sbook2.html#Conc2 accessed 19 March 2009

4. Ibid.

5. Sawyer, Mary R. Black Ecumenism: Implementing the Demands of Justice.Valley Forge, PA: Trinity Press International, 1994. p. 1.

6. Ibid., p. 8.

7. Paris, Peter. The Social Teachings of the Black Church.Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press. p. 129.

8. Capitol Hill Group Ministry, Interfaith Service of Thanksgiving Program, Capitol Hill SDA Church, Washington DC, 2006.

9. “This Is the Day That the Lord Has Made.” Text from Psalm 118:24. Tune by Les Garrett.

10. “They Will Know We are Christians by Our Love.” By Peter Scholte.

11. “NCC at a Glance: Who Belongs, What We Do, How We Work Together.” National Council of Churches. Online location: http://www.ncccusa.org/about/about_ncc.htm accessed 19 March 2009

12. “A Brief History.” The Interreligious Foundation for Community Organization. Online location: www.ifconews.org accessed 19 March 2009

13. King, Wayne. “Prosecution Drops Murder Case against 5 Defendants in Georgia.” The New York Times. 20 December 1977.

Sample 11 Days Plan for an Ecumenical Celebration

|