Sunday, February 17, 2008

Bernice Johnson Reagon, Lectionary Team Cultural Resource Commentator

I. Historical Background And Documents

A. Thoughts on the Balancing Contributions of Martin Luther King, Jr. and

Malcolm X: to African American culture, organized human culture–regarding

Nonviolence as a Transformative Force and the Necessity for Cleansing by

Righteous Anger.

The MAAFA concerns, among other things, acknowledging, remembering and

understanding, the ways in which African Americans have struggled against

oppression in America, after being forcibly brought here on slave ships. Often,

our national memory is skewed or at least anemic in areas. When I teach African

American History and we get to the Civil Rights Movement, it never fails that my

students think that Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. came first and was followed

or revised by Malcolm X. It is important for us all to understand that these men

were brothers moving within America during the same time period using different

approaches to obtain justice. These approaches represented the balance needed to

overcome oppression. It is with this sense of balance that at the same time

African Americans faced down the forces of racial segregation, street by street

with our very lives, and committed not to respond with hate and physical

violence; it never meant that we were not being confrontational.

Indeed, Civil Rights activism within local communities aimed to paralyze the

local structure, to force setting of a new agenda on race, segregation, and

access. It was activism spirited and energized by gifted souls which led to

the discovery that through the commitment not to kill, one could fight racism

and discover transformative restorative love, which was a new offering from

African Americans as they struggled for their basic rights and for the rights of

others. And Brother Malcolm saying it is healthy to be angry and pissed off about

how black people had been treated in this nation of our birth, was fearful,

threatening, and cleansing. Malcolm X, more than any other presence, inserted

into the African American cultural canon the right and necessity to express

anger. He showed us that “keeping the peace–by holding your peace” is not a

noble virtue. Yes, we had been taught that if we stepped out of line we might

be killed, but Malcolm suggested that a person cannot “stay in line” without

distorting and self-wounding his or her soul. The Civil Rights Movement

demonstrated that everybody has something to give to transform conditions we

find ourselves aching to change… one has a life to offer so that while the

blood runs warm in our veins, we do not have to sit by and watch evil in silence.

We must always acknowledge, remember, and understand this.

B. Marimba Ani And MAAFA

Dr. Marimba Ani in her work Let the Circle Be Unbroken (1989) uses MAAFA,

(the Kiswahili word for disaster, terrible occurrence or great tragedy) to

describe the African Holocaust (the complete devastation or destruction of the

African people, which resulted from the enslavement of Africa’s human resource)

as the most destructive act ever perpetuated by one people upon another. “Within

the setting of our enslavement, the ideology of white supremacy was systematically

reinforced by a set of interlocking mechanisms and patterns that functioned to

deny the validity of an African humanity.1

The MAAFA translated into English means “The Enslavement of (Mama) Africa.”

However, the word MAAFA, when translated to English, is also used to define the

words menace, threat, terror, and most importantly injustice. These words fully

encapsulate the threat of an invading Arabic and European menace that terrorized

Mama Africa and perpetrated a great injustice upon her and her children. The

capitalization of the word MAAFA accentuates the magnitude of the injustice

committed against Mama Africa and her children, for it was her natural resources

as well as the African people who were raped, plundered, and murdered.

Dr. Ani introduced the concept of The MAAFA into contemporary African American

scholarship as a preferred reference to the period in world history identified

as the Middle Passage or trans-Atlantic slave trade.2 MAAFA observances

bring people into closer communion with ancestors who perished during the

trans-Atlantic slave trade. By some estimates, 50 to 75 million African men,

women, and children were stolen from Africa and warehoused for shipping to the

Western Hemisphere. Some died in the bellies of slave ships on the high seas en

route to an unknown destiny. Other died in the slave fortresses along the coast

of West Africa, and many died during violent raids on African villages. Without

a knowledge of history, many may be unaware of the fact that Islamic traders

carried on a steady slave trade from East African ports for many centuries

(even before the Europeans) resulting in the deaths of many more Africans during

the long and treacherous journeys from the interior to the east coast.3

All of them are remembered and honored during MAAFA observances. In her book,

Dr. Ani also speaks of the importance of Africans in America using African

language to define their history and experiences, and her search through various

African languages, to find a term that would let us uniquely claim this

experience.

II. African American Use of Swahili, And Bantu’s Influence And Reach…

One might wonder why African Americans so often reach for Swahili as we pull

elements of Africa into the weave of our existence in the United States of

America. Most of us are unaware that the concept of Africa as a unified presence

was born out of the Middle Passage and the trans-Atlantic slave trade. On the

continent of Africa, cultural identity was born out of specific cultural and

tribal groups. When African Americans began to reach for Africa we were not

restricted by specific cultural groups, we were more interested in accessibility.

In a contemporary sense, it is said that we are drawn to Kiswahili because we

like the sound, we find it accessible, and it is a hybrid language of exchange

evolved over centuries and cultures moving and intersecting. I find it

interesting to consider that Swahili is a Bantu language and the Bantu people

began their journey out of western Africa thousands of years ago and wherever

they moved, the culture exchange left a Bantu imprint.

Ani’s work belongs to a tradition of activist cultural scholars and creators who

are committed to consciously contributing to the work of continued transformative

survival of African Americans. MAAFA services are a part of that work.

There is an African proverb that says “to forget is the same as to throw away.”

The idea of finding healing from acknowledging the pain, degradation, and horror

of the past is finding many supporters among African American scholars and

healers across the United States. Dr. Na’im Akbar has long expressed his belief

that much of what ails African Americans had its origins in the Middle Passage

and the enslavement of Africans in America. He contends that the trauma our

ancestors endured was so profound and has gone untreated for so long that

African America suffers from what he calls “posttraumatic slavery disorder.”

Commemorating The MAAFA encourages people of African descent to confront the

ghost and demons of the past head-on, in order to move beyond these psychic

wounds. It is not about blame or finger pointing. It’s about finding a way to

heal and move beyond the many wrongs this nation and others have perpetrated in

the name of profit and power.4

III. Historical Writings That Provide Insight

A. Excerpts from the book “Slavery and the Slave Trade”5

Slaves attempted to preserve the culture that they brought with them from Africa.

Jeanette Murphy recalled: "During my childhood my observations were centered upon

a few very old Negroes who came directly from Africa, and upon many others whose

parents were African-born, and I early came to the conclusion, based upon negro

authority, that the greater part of the music, their methods, their scales, their

type of thought, their dancing, their patting of feet, their clapping of hands,

their grimaces and pantomime, and their gross superstitions came straight from

Africa." Attempts were made to stop slaves from continuing with African religious

rituals. Drums were banned as overseers6

feared that they could be used to send messages. They were particularly concerned

that they would be used to signal a slave uprising.

B.Frederick Douglass Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845)

“While on their way (to work), the slaves would make the dense old woods, for

miles around, reverberate with their wild songs, revealing at once the highest

joy and the deepest sadness. They would compose and sing as they went along,

consulting neither time nor tune. The thought that came up, came out, if not in

the word, in the sound; and as frequently in the one as in the other. They would

sometimes sing the most pathetic sentiment in the most rapturous tone, and the

most rapturous sentiment in the most pathetic tone. This they would sing, as a

chorus, to words which to many would seem unmeaning jargon, but which,

nevertheless, were full of meaning to themselves. I have sometimes thought that

the mere hearing of those songs would do more to impress some minds with the

horrible character of slavery, than the reading of whole volumes of philosophy on

the subject could do.”7

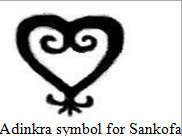

IV. Sankofa And the Importance of Memory

Those who have suffered unspeakable atrocities may want to forget. However, it is

important to remember the evil of the past so that it is not repeated. The word

Sankofa can mean either the word in the

Akan language of

Ghana that translates in English to "go back and take"

(Sanko- go back, fa- take) or the Asante

Adinkra

symbol.

The Asante of Ghana use an Adinkra symbol to represent this same idea and one

version of it is similar to the eastern symbol of a heart, and another version is

that of a bird with its head turned backwards taking an egg off its back. It

symbolizes taking from the past what is good and bringing it into the present in

order to make positive progress through the benevolent use of knowledge.

This is another reason we must remember The MAAFA.

Adinkra symbols are used by the Asante to express

proverbs

and other philosophical

ideas. These ideas are numerous and are used throughout the world because of

their aesthetic and spiritual beauty. Sankofa has since been adopted by other

cultural groups in the area and around the world.8

V. A Story to Remember: The Death of Emmett Till

Few events galvanized the fight for racial justice than the death of Emmett Till.

May we never forget the role of his story in our larger story.

“Have you ever sent a loved son on vacation and had him returned to you in a

pine box, so horribly battered and water-logged that someone needs to tell you

this sickening sight is your son -- lynched?” These are the words of Mamie Till

Bradley Mobley, the mother of Emmett Till.

In August 1955, Emmett, a fourteen year old, bright and handsome boy went to

visit relatives near Money, Mississippi. Emmett had experienced segregation in

his hometown of Chicago, but he was unaccustomed to the severe segregation he

encountered in Mississippi. He is said to have either whistled or made a

flirtatious comment to Carolyn Bryant, the wife of a local storeowner while in a

store.

A few days later, two men came to the cabin of Mose Wright, Emmett’s uncle, in

the middle of the night. Roy Bryant, the owner of the store, and J.W. Milam, his

brother-in-law, drove off with Emmett. Three days later, Emmett Till’s body was

found in the Tallahatchie River. One eye was gouged out, and his crushed-in head

had a bullet in it. The corpse was nearly unrecognizable; Mose Wright could only

positively identify the body as Emmett’s because he was wearing an initialed

ring.

Bryant and Milam were arrested for kidnapping even before Emmett's body was

found. The Emmett Till case quickly attracted national attention. Mamie Bradley,

Emmett's mother, asked that the body be shipped back to Chicago. When it arrived,

she inspected it carefully to ensure that it really was her son. Then, she

insisted on an open-casket funeral, so that “all the world could see what they

did to my son.” Over four days, thousands of people saw Emmett’s body. Many more

blacks across the country who might not have otherwise heard of the case were

shocked by pictures that appeared in “Jet” magazine. These pictures moved blacks

in a way that nothing else had. When the “Cleveland Call” and “Post” polled major

black radio preachers around the country, it found that five of every six were

preaching about Emmett Till, and half of them were demanding that “something be

done in Mississippi now.”

The two men went on trial in a segregated courthouse in Sumner, Mississippi on

September 19, 1955. In the end, Defense attorney John C. Whitten told the jurors

in his closing statement, “Your fathers will turn over in their graves if

[Milam and Bryant are found guilty] and I’m sure that every last Anglo-Saxon one

of you has the courage to free these men in the face of that [outside] pressure.”

The jurors listened to him. They deliberated for just over an hour, then returned

a “not guilty” verdict on September 23, the 166th anniversary of the signing of

the Bill of Rights. The jury foreman later explained, “I feel the state failed to

prove the identity of the body.” In Mamie Bradley Mobley’s words, “Two months ago

I had a nice apartment in Chicago. I had a good job. I had a son. When something

happened to the Negroes in the South I said, ‘That’s their business, not mine.’

Now I know how wrong I was. The murder of my son has shown me that what happens

to any of us, anywhere in the world, had better be the business of us all.”9

In September 2005, the Till Bill was passed by the United States Congress

creating a new Federal Unit within the Justice Department to Probe old Civil

Rights cases.

VI. Song Texts

Paul Robeson was interviewed about music by R. E. Knowles for the

Toronto Daily Star. (November 21, 1929):

“The African people have an almost instinctive flair for music. This faculty was

born in sorrow. I think that slavery, its anguish and separation - and all the

longings it brought- gave it birth. The nearest to it is to be found in Russia,

and you know about their serf sorrows. The Russian has the same rhythmic

quality - but not the melodic beauty of the African. It is an emotional product,

developed, I think, through suffering.”

Waters (rivers) of Babylon

Sacred Song from the Jamaican Christian and Rastafarian traditions

It would be from this side of the water, this side of the Middle Passage, that

the descendants of that journey created our singing. Here we first hear the

remembering of captivity, then of the captors asking us to sing some of our songs

of Zion. It is not surprising that we like the Psalmist in Zion have asked–How can we sing the songs of our knowingness in this strange land? And that to

answer the question some of the creators of our songs reached for the fourteenth

verse of Psalm 19 with a commitment to sound, our survival, and perseverance to

the elements, and to know we are. As a singer of African American traditional

songs, I know that we sing to know that “we are” and to know “who we are” and to

offer that knowing and presence to the universe.

Text from Psalm 137:1-5, and Psalm 19:14

By the waters of Babylon (2x)

Where we sat down

And there we wept

When we remembered Zion

Oh the wicked carried us away to captivity (2x)

Required of us a song

How can we sing our holy songs in a strange land

So let the words of my mouth (2x)

And the meditation of my heart

Be acceptable in thy sight, Oh Zion (“Over I”)

On Remembering10

I Remember, I Believe

I don’t know how my mother walked her trouble down

I don’t know how my father stood his ground

I don’t know how my people survive slavery

I do remember that’s why I believe

I don’t know why the rivers overflow their banks

I don’t know why the snow falls and covers the ground

I don’t know why the hurricane sweeps thru the land every now and then

Standing in a rainstorm, I believe

I don’t know why the angels woke me up this morning soon

And I don’t why the blood still runs thru my veins

I don’t how I rate to run another day

I am here still running, I believe

My God calls to me in the morning dew

Power of the Universe knows my name

Gave me a song to sing and sent me on my way

I raise my voice for justice, I believe

I Be Troubled

I be troubled

I be troubled

I be troubled ‘bout my time done long gone

I be troubled

I be troubled

I be troubled ‘bout my time done long gone

I be worried…

I be worried in the bottom of my being here…

I be trying…

I be trying to keep my mind about me

I be worried…

I be worried how my spirit just cried out…

In the morning…

I don’t feel like seeing the sun come shining

Why Did They Take Us Away

Why did they take us away?

Why did they take us away?

Why did they take us away?

I can’t reach out my arms

I can’t reach out my arms

I stand on shifting sands

I hold on to my song

I hold on to my song

It makes me know my name

My sun is burning high

My sun is burning high

Come watch my golden flame

I can’t roll back the years

I can’t roll back the years

I must keep moving on…

Notes

- Ani, Marimba. Let the Circle Be Unbroken: The Implications of African

Spirituality in the Diaspora. New York, NY: Nkonimfo Publications, 2007

(originally published in 1989, Dona Marimba Richards, copyright, 1980).

- Ibid.

- Lewis, Bernard. The Arabs in History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Lewis, Edmond W. Honor and Memory. The Louisiana Weekly. New Orleans:

Louisiana Weekly Pub. Co., June 28, 2004. Online location:

www.louisianaweekly.com accessed 5 December 2007

- Walvin, James. Slavery and the Slave Trade: A Short Illustrated History.

Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 1983.

- “Overseers” Simkin, John. ed. Spartacus Educational. Online location:

www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/USAoverseers.htm accessed 5 December 2007

- Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- "Sankofa." Wikipedia 26 Jan. 2008. Online location: Reference.com

www.reference.com/browse/wiki/Sankofa accessed 5 December 2007

- Cozzens, Lisa. “The Murder of Emmett Till (Early Civil Rights Struggles).”

25 May 1998. African American History. Online location:

fledge.watson.org/~lisa/blackhistory accessed 5 December 2007

- Songs written by Bernice Johnson Reagon, Washington, D.C.

|